http://www.dnaindia.com/money/report-what-chinese-dam-on-brahmaputra-means-to-india-2038737

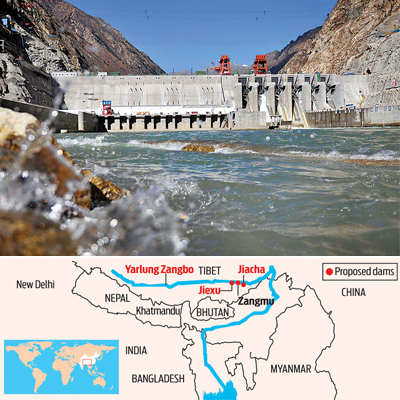

What Chinese dam on Brahmaputra means to India

Two days ago, on Sunday, China operationalised its first major dam on the middle reaches of the Brahmaputra. The first section of the 510 MW project began generating power.

China’s official Xinhua news agency said the first section of the $1.5 billion dam went into operation on Sunday afternoon. Five other sections will be completed next year. The dam will generate 2.5 billion kilowatt hours of electricity every year, reported the agency.

China’s official Xinhua news agency said the first section of the $1.5 billion dam went into operation on Sunday afternoon. Five other sections will be completed next year. The dam will generate 2.5 billion kilowatt hours of electricity every year, reported the agency.

The implications of construction of the dam for India are on several fronts. It reduces water flow in the river. This is not so serious if the dams are RoR (run of river) hydro stations. But if reservoirs are built, or waters diverted, it could affect the river’s ecosystem in the upper stretches.

Second, it gives China a stronger say in water sharing discussions because it has established claim of use of these waters. India will have to move quickly to establish its own user rights quickly.

Also, rapid development of infrastructure in the N-E could create social tensions with local tribes. That must be avoided to prevent China instigating Arunachal Pradesh locals to agitate against India.

The Zangmu dam construction began in 2010. It sparked off panic among China’s southern neighbours, including India. The fear was that China may actually drain this river of water, just as it had done with the Mekong river.

The 4,350 km long Mekong is the 12th largest river in the world, the 7th largest in Asia. It originates from Tibet (China) and flows through Myanmar, Laos, Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam. Today, all the downstream countries of the Mekong river accuse China of starving them of water.

Could this become the fate of India’s North-East and Bangladesh as well? This is because out of the Brahmaputra’s total length of 2,880km, 1,625km is in Tibet (or China), 918km in India, and 337km in Bangladesh.

After all, China’s water resources are scantier than India’s and its needs many times greater (http://www.dnaindia.com/money/report-russia-india-china-the-new-global-centre-of-gravity-1993067) — never mind the fact that India squanders even the plentiful water that it has (http://www.dnaindia.com/money/report-policy-watch-india-splurges-51-of-water-it-could-have-otherwise-saved-1995733).

But, on the other hand, the average annual rainfall is just 400mm in Tibet, but 3,000mm on the Indian side. This is in spite of the fact that (according to data provided by the Central Water Commission), of the total catchment area of 580,000 sq km, 50% lies in Tibet, 34% in India, and the balance in Bangladesh and Bhutan. Significantly, only 40% of the water comes from the Chinese catchment area.

Some policymakers in Delhi believe that the precipitation in China contributes only 7% to the flow. It is the Brahmaputra’s tributaries in Arunachal Pradesh, along with the rains in India, that contribute to the rest of the river’s water supply.

That could explain the absence of any shrill reaction from New Delhi. But there is tremendous cause for concern.

First, many experts believe that the 7% precipitation theory is all hogwash. You cannot compartmentalise any river, they say. Brahma Chellaney, a noted China and water expert, warns that any diversion of water from the upper reaches of the Brahmaputra could have devastating consequences for the way the river flows for downstream areas (http://www.dnaindia.com/india/report-india-losing-water-war-1982524). He believes that all sorts of data is being fed to journalists, and that the only reliable data is from the United Nations.

According to the United Nations, the cross border annual aggregate flow of Brahmaputra river system is around 165.4 billion cubic metres (bcm). That, add experts, is greater than the combined trans-boundary flow of the three key Asian rivers—Mekong, Salween and Irrawady—that run from the Tibetian plateau to South East Asia.

Second, reservoirs along the river could staunch the flow of water into India. True, most of the hydro-projects China is building are of the run-of-the-river (RoR) type, generating electricity from the flow of the river and not trapping any of the water in dams. However, reservoirs are also being built, and it is only a matter of time that much of the water originating and collected in China could get trapped in reservoirs for diversion to the northern parts of China.

But, most critically, almost every policymaker in New Delhi is painfully aware that under international law, a country’s right over natural resources it shares with other nations becomes stronger if is already putting these resources to use. China has already begun first use of the Brahmaputra waters.

If India does not move fast and establish its own claims over water use, it could lose out in subsequent water sharing discussions under international law.

That partly explains the Modi government’s urgency in building projects and linking Arunachal Pradesh to the rest of India. It also throws light on why Indian strategists are suspicious of any moves by environmental groups protesting against the setting up of such projects along the Brahmaputra.

COMMENTS