https://www.moneycontrol.com/news/business/ningbos-rise-as-the-worlds-largest-port-has-lessons-for-india-4719711.html

Ningbo was India’s trading partner even 2,000 years ago; then the Indian government turned myopic about trade

RN Bhaskar — 11 Dec, 2019

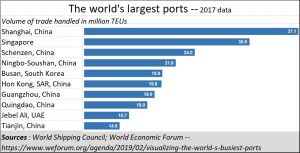

Last year, the world-port-ranking underwent a change, when Ningbo-Zhoushan in south east China became the largest port in the world. By then, it had built trade channels with over 600 ports spread across 100 countries. The port which handles all types of cargo — container, liquid and dry bulk – accounted for an annual cargo throughput of over a billion tonnes last year (https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201901/16/WS5c3ec2d7a3106c65c34e4cc4.html). Added a port official, quite matter-of-factly “Overall, the total cargo throughput of Ningbo Zhoushan Port was 1.08 billion metric tonnes in 2018. By the end of 2019, our traffic volume data will further grow. There is some good growth expected.”

He was proud that his port had managed to race past Shanghai (see chart). Around a decade ago, the largest port used to to Singapore. Then it became Shanghai and now it is Ningbo-Zhoushan. What is even more interesting is that seven of the top ten ports are now from China.

He was proud that his port had managed to race past Shanghai (see chart). Around a decade ago, the largest port used to to Singapore. Then it became Shanghai and now it is Ningbo-Zhoushan. What is even more interesting is that seven of the top ten ports are now from China.

But Ningbo’s growth is not unexpected. It has been a trading port for over 2,000 years. It had extensive trading links with India. As described by author Kanakalatha Mukund in her book titled The World of the Tamil Merchant (Penguin), there is enough evidence of the way Indian merchants from South India traded extensively with China. “The goods traded covered a vast range of utility and luxury products from food grains and pepper to cloth, aromatic substances and precious gems like corals and pearls”.

And as trade developed, “the ports on the east and west coasts of India, strategically located in the geographic centre of this region, became entrepôts of commercial exchange and of cultural diffusion since merchant ships from the west rarely sailed further east beyond the Bay of Bengal, while the ships from the east, especially China, did not venture further west than the ports of Kerala,” explains Mukund.

Indian merchants, even then, acknowledged the superior maritime skills and power of China, and often paid tributes to China’s kings: “For more than one millennium, [Chinese] kingdoms retained strong links with India through religious and cultural interactions. However, China was the great empire and political power for the entire region and embassies were regularly sent to the Chinese court by all the kingdoms—Champa, Kambuja and the Sailendras of Sri Vijaya—which implicitly acknowledged the superior status of China as a superpower both politically and economically. The embassies sent to China by the Chola emperors, Rajaraja I in 1015, Rajendra I in 1033 and Kulottunga I in 1077, in effect accepted the centrality of China for maintaining the political and economic power balance in the region.”

India lost that sense of perspective, and actually tried to minimise trade with China, much to its own disadvantage.

India lost that sense of perspective, and actually tried to minimise trade with China, much to its own disadvantage.

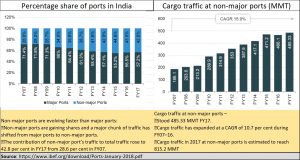

So why did India lose out on maritime trade? Just look at the numbers. The entire country accounted for cargo volumes of under 500 million tonnes in 2017 (the latest figures given out by the maritime trade as yet). In China, just one port, Ningbo, accounted for over a billion tonnes.

Reason one: The government’s own lopsided attitude towards ports in India. Of course, it likes to wax eloquent about its achievement. Consider this government release of 13 December 2018: (https://pib.gov.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=186373) — “Aided by the progressive policy interventions, the capacity and efficiency of Major Ports rises yet again in 2018. Ease of Doing Business a major focus during the year. Inland Water Transport poised for big Growth with the launch of First Multimodal Terminal on Ganga. Rise in Cargo Movement and Expansion of Ro Ro Services. Sagarmala sees the completion of 89 projects . . .”

The government still talks about government-owned ports as Major Ports, even though its share of cargo business in India has been shrinking year after year (see chart). The ministry refuses to give data on non-government ports, and when it does so, it is scant. Instead of looking at the entire country’s maritime business, it seems keen on projecting just government-owned ports.

Second, historically, most heads of governments have been from land-locked areas. They possibly failed to recognise the strategic significance of ocean transport and sea-farers. Even currently, it is trying to relax cabotage rules in favour of foreign flag ship owners instead of promoting Indian flags (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2018/10/indian-shipping-grows-overseas-not-in-india/). The government has introduced tax policies that encourage Indian shippers to grow under foreign flags instead.

Third, India has always looked at export and import with suspicion. It has not encouraged and trusted trade. As a result, both imports and exports have suffered, and consequently India’s growth as well.

Fourth, culturally, India was distrustful of the sea. As a result, crossing the seas was discouraged. When people like Mahatma Gandhi and Lokmanya Tilak went overseas for higher studies and returned to India, they had to undergo purification rites (shuddhikaran). Even mythology shows Lord Rama, in search of his kidnapped wife, opt to build a bridge across the seas to reach Sri Lanka when boats could have sufficed. He was warned by the ocean gods not to cross the seas by boats. As a result, much of sea trade was carried on by non-Hindu communities (till some of them were adopted and merged into the Hindu mainstream). As a result, India did not develop naval strength.

Lastly. India has quietly side-lined some of the most capable officers capable of promoting coastal business and transport. A country does not grow big when its most capable people are marginalised.

Instead Ningbo, which has quietly, though the centuries, kept building its maritime capabilities and trade volumes. China has obviously learnt from Singapore and Hong Kong, that for volumes to grow, one needs to be more efficient, less bureaucratic, so as to convert its best ports into trans-shipment hubs. Both Singapore and Hong Kong consume a fraction of the cargo throughput. The rest moves on to other destinations. India has not been nimble on this front as well.

Ningbo’s rise as a port thus has several lessons for India. It shows how a country’s ports can continue growing in spite of a global economic slowdown. It shows how maritime trade and economic prosperity are closely intertwined, as are cultural linkages between countries. Even today, additional investments are being made to make this a truly multi-modal port with air, road and rail linkages. Moreover, it is immensely profitable. It is listed on the stock markets, and made a net profit of RMB 5 billion (one RMB or yuan is worth around 10 rupees) and expects to grow further in time to come. The entire profit came from loading and unloading businesses and does not include any space rental business income at all.

Can Indian ports become this big. Yes, only if government policies are willing, and growth, not politics, assumes prime focus.

COMMENTS