Government norms for ranking vocational institutes are shortsighted, even harmful

By RN Bhaskar

Ever since the Union Budget got announced barely a month ago, there has been a lot of buzz around the offices of the Directorate General for Vocational Education. The concept of vocational education is not new. It was first brought within the purview of government focus during the 1970s when the 10+2+3 system was introduced. The idea then was to vocationalise the plus-2 part of the system.

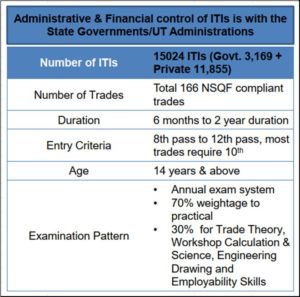

Unfortunately, most educational institutes opted to make all subjects largely theoretical. The emphasis on the vocational part was missing. Paucity of funds and vision caused the vocational part to be forgotten except by institutes which were focussed solely on vocational education – namely the ITIs (or Industrial Training Institutes). ITIs, in India, are regulated by the Directorate General of Training (DGT)

Now there is renewed interest in vocational courses. The Budget announced an additional outlay Rs 60,000 crore for ranking vocational education institutes. Rs.30,000 crore would come from the Centre, Rs 20,000 crore from states, and the rest expected to be mobilised by industry.

Now there is renewed interest in vocational courses. The Budget announced an additional outlay Rs 60,000 crore for ranking vocational education institutes. Rs.30,000 crore would come from the Centre, Rs 20,000 crore from states, and the rest expected to be mobilised by industry.

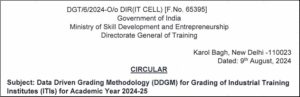

The government’s method of galvanising the nearly 15,000 ITIs across the country is by ranking them and the n using these rankings for pumping funds into better institutions. It brought out two documents that seem to make its resolve and intent clear. One is a presentation by the DGT. The other is a circular from the office of the DGT dated 9 August 2024.

The government’s methodology looks interesting, but for a few major bugs.

The first problem is obvious in the circular that the DGT sent to all ITIs in the country. It talks about the methodology that is to be followed for grading institutes for the Academic Year 2024-25. It is good that the government is finally coming out with the norms that will be used for evaluating and ranking such institutes. The problem is that instead of discussing such norms and processes with academics and professionals, the directorate has adopted norms that are bizarre.

The second problem is with the data. One such table shows that there are some 15,000 ITIs spread across the country. They offer courses in 166 trades. The chart shows that 70% of the weightage will be given to practicals. Only 30% will be allocated for the rest of the courses including workshop calculation and science.

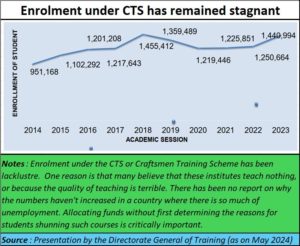

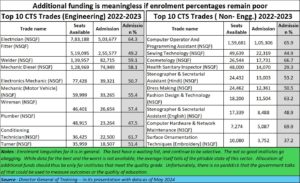

Then there is the problem of poor enrollment. The government is pouring out money for courses and institutes that do not seem to be attracting students. It must first find out why students have not enrolled for such courses, especially when the country is reeling under unemployment.

Then there is the problem of poor enrollment. The government is pouring out money for courses and institutes that do not seem to be attracting students. It must first find out why students have not enrolled for such courses, especially when the country is reeling under unemployment.

Is it because the courses are not relevant to market needs and demands? Or is it that the teachers do not teach well, and the students learn more outside the classrooms than inside them? My own exposure to the teaching environment – I was on the sub-committee advising the government on vocational education as early as in 1976 – makes me suspect that the reason could be the ineptness of the teaching environment.

Even in the latest year for which data is available, average enrolment is poor. The government has poured money into creating facilities and teaching establishments which do not endear themselves to the students. At one end of the spectrum are institutes that have a waiting list of candidates. On the other are institutes (often government owned) which go a-begging for students.

Even in the latest year for which data is available, average enrolment is poor. The government has poured money into creating facilities and teaching establishments which do not endear themselves to the students. At one end of the spectrum are institutes that have a waiting list of candidates. On the other are institutes (often government owned) which go a-begging for students.

Surely, the norms for ranking institutes should be based on the quality of education and placement of students after they graduate. Unfortunately, with the government being the largest player in this market, most of the policies appear to be drafted in such a way that they protect government institutions, and ensure that their ranking remains high.

Non-government players are too fragmented. The largest non-government player is Don Bosco, also reputed to be among the best vocational training managements in India. The other private players are far too small.

Non-government players are too fragmented. The largest non-government player is Don Bosco, also reputed to be among the best vocational training managements in India. The other private players are far too small.

Just look at the chart which gives the weightages for evaluating vocational training institutes.

First, the clause that looks for new emerging trades is not fair. Vocational institutes offer courses for which there is demand. That demand is created by the marketplace. Demand cannot be created by the government. Hence if an institute offers those courses which students like, that should not be discouraged. If the government wishes to promote a new course, it should offer select institutes additional incentives for promoting them.

The only institutes that can offer courses without looking to relevance or viability are government institutes which are then offered funds by the government. These institutes then have a better chance of being ranked higher than others.

That brings us to another problem. An institute cannot be judged merely on the number of students it enrols. Indian institutes have seen students enrolling, especially if they come from backgrounds which are granted financial and non-financial subsidies by the government. But they drop out of these courses when they believe that the course (or the institute) is not appealing enough.

What must be looked at is the number of students who appear for the final examinations as a percentage of intake capacity. That is how one separates the men from the boys. Merely looking at enrolment numbers can be highly misleading.

Measuring outcomes

A third problem is that looking merely at marks obtained by students can be counter0productive. This is especially so when 70% of the marks are given on the basis of practicals – which means internal evaluations. Faculty of institutes can be liberal with their marks, making the comparison on scores across institutions quite misleading. If marks must be considered, it must be only the 30% marks that have been secured at a uniform board examination. Better still, the government must put into place a method to measure outcomes – of students, of teachers and even of institutes.

Thus, if a batch of students had secured an average of 40% marks at the last examination before they got enrolled, and if most do not get higher marks at the board level, there should be a cause for concern. At that moment, external evaluators must step in and examine how teachers teach, and how students learn. If the institute itself does not help students score higher marks than what they had obtained at the last examination before enrolment, that institute should me marked as one not performing well enough, and subjected to further scrutiny. In case some institutes fail to make the grade year after year, they should be handed over to the best private sector, or the best performing government institutes. Measurement of outcomes is crucial if the government is serious about education.

What about measuring unemployability?

Finally, nowhere is there a parameter that measures placement of students as a percentage of students appearing for the final examinations. This is important because the offer of vocational courses to students becomes meaningless if they cannot become self-employed or can be placed in organisations. Institutes must maintain such a database.

Institutes should be ranked based on the number of students who managed to make use of their training and get employment or start their own business. The latter will require some cross-checking with social service organisations, so that bogus statements do not get filed. Monitoring employability must be done in conjunction with social service organisations – preferably NGOs who have been active in promoting economic welfare among youth. A good example of one such organisation is SEWA.

A cul-de-sac

The way the government has devised norms for education leaves much to be desired. These are norms that will ensure that the best institutes do get ranked over government institutes, and thereby curtail their sphere of influence and their ability to grow.

It is a surefire way of destroying vocational education.

The author is a senior journalist and researcher

==================

Do watch my latest podcast — a conversation with Abizedr Diwanji on Agri-tax reforms at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rT5mHXxC5g0

COMMENTS