Government favours importers of pulses not Indian farmers

By RN Bhaskar and Sakeena Bari Sayyed

Image generated through CoPilot

Last week farmers decided to approach the Supreme Court of India to seek redressal of the government’s pulses policy. Normally, the government takes policy decisions which shape the agricultural sector. But this time the farmers growing pulses appear to have lost confidence in the government’s ability to craft a suitable policy which benefit farmers and consumers alike, and not just importers and foreign farmers.

In fact, it appears that the centre is brazen about its immense desire to promote importers. Look at what it did earlier this year. It actually extended the validity of a circular for importing pulses.

Such moves leave common observers perplexed. On the one hand you have the prime minister telling then people that he will protect farmer interest even at the cost of his own life. He has made the stand even more vocal after the US President Donald Trump tried to compel India to purchase its agricultural produce.

Such moves leave common observers perplexed. On the one hand you have the prime minister telling then people that he will protect farmer interest even at the cost of his own life. He has made the stand even more vocal after the US President Donald Trump tried to compel India to purchase its agricultural produce.

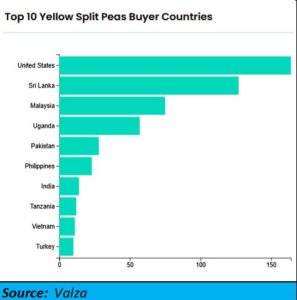

On the other hand, it makes one wonder if this stand was primarily meant for the US or for all agricultural produce exporting countries looking for a market in India. It may be worth recalling that when it comes to pulses, India is among the top 10 pulses importers in the world.

On the other hand, it makes one wonder if this stand was primarily meant for the US or for all agricultural produce exporting countries looking for a market in India. It may be worth recalling that when it comes to pulses, India is among the top 10 pulses importers in the world.

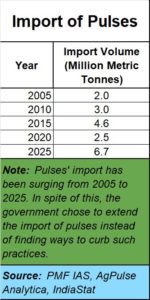

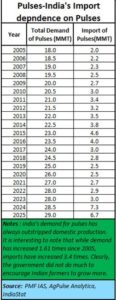

A closer look at data makes one realize that the farmers have very good reasons to complain. This is not the first time that the government has decided to resort to import of pulses. Even a cursory look at available data shows how India’s import of pulses has been on the ascendant.

Drill a little deeper and you will discover some more worrying patterns. Imports of pulses have increased faster and more rapidly than domestic production. And, the excuse the government often gives, of resorting to imports to cool domestic prices, is also shown to be a fictitious tale. Look at the chart below.

Drill a little deeper and you will discover some more worrying patterns. Imports of pulses have increased faster and more rapidly than domestic production. And, the excuse the government often gives, of resorting to imports to cool domestic prices, is also shown to be a fictitious tale. Look at the chart below. The chart shows that domestic production of pulses barely doubled during the past twenty years. But imports grew three times during the same period. Clearly, the policies ought to have been aimed at galvanising domestic production. Instead, the government has provided more opportunities to importers.

The chart shows that domestic production of pulses barely doubled during the past twenty years. But imports grew three times during the same period. Clearly, the policies ought to have been aimed at galvanising domestic production. Instead, the government has provided more opportunities to importers.

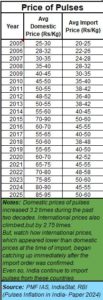

Look at another chimera that the government has often created. It often says that it resorts to imports only to cool domestic prices so that consumers do not get hurt. Really?

Look at the table below. It is about how domestic and import prices have worked during the same period.

You will observe that each time domestic prices are high, the government finds an excuse to justify imports to cool domestic prices. But the data above shows that immediately thereafter, international prices also go up. Thus, the cost advantage promised to consumers was only illusory. The prices kept going up. International producers appear to have benchmarked future prices against Indian domestic prices. Indian producers also began increasing the prices in sync with global prices. The upward spiral continued. In the last twenty years domestic prices have climbed 3.2 times while international prices 2.75 times. You can expect international prices to climb once again to match domestic prices. It is a rigged market where Indian farmers and consumers both get cheated. The only ones grinning all the way to the bank are global producers and their comrades in the Indian government.

You will observe that each time domestic prices are high, the government finds an excuse to justify imports to cool domestic prices. But the data above shows that immediately thereafter, international prices also go up. Thus, the cost advantage promised to consumers was only illusory. The prices kept going up. International producers appear to have benchmarked future prices against Indian domestic prices. Indian producers also began increasing the prices in sync with global prices. The upward spiral continued. In the last twenty years domestic prices have climbed 3.2 times while international prices 2.75 times. You can expect international prices to climb once again to match domestic prices. It is a rigged market where Indian farmers and consumers both get cheated. The only ones grinning all the way to the bank are global producers and their comrades in the Indian government.

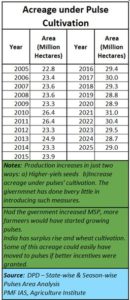

Just look at the glib justifications given by government functionaries to justify the need for import (https://asiaconverge.com/2017/05/pulses-and-the-need-to-protect-indian-agriculture/). At times, even though the government knew that acreage under pulses had increased, imports were resorted to. Analysis of data for the past two decades shows how glib these explanations have been.

Given the penchant of the government to resort to imports without any warning has often caused domestic prices to fall because of cheaper imports at that point of time. As a result, farmers have been reluctant to increase their acreage under pulses cultivation. Poor investment by the government in creating new seed varieties which can boost yields has also meant no surge in production despite the limited acreage. Hence, domestic production has not gone up. That has given the government further justification for importing pulses again and again.

To understand what the solution should be it is important to look at data again. Domestic demand for pulses has gone up only 1.6 times in the past two decades. Imports have however climbed 3.4 times. Obviously, this means that domestic production was stunted in order to allow imports to grow faster.

This is sad because the government has spent more legislative time on rice, wheat and corn. These are the crops that enjoy procurement by the Food Corporation of India (FCI) at ever increasing MSPs. These crops are largely grown in the Hindi belt which is a major vote bank for any government at the centre. That could explain why policies are created for these crops to deter imports. Other states and crops are however not so fortunate.

This is where national policy needs to change. There was a time when rice and wheat were synonymous with food security. Today, India produces more rice and wheat than it needs and much of it goes rotten each year given the poor storage facilities in India (https://asiaconverge.com/2017/08/is-wdra-a-functioning-organisation/).

Today what India needs is more nutrition. That means more pulses. Rice and dal are better than rice alone. Ditto with chapatis and dal. The government needs to encourage more rapid domestic demand for pulses. For that it must also encourage more production both through higher MSPs as well as procurement through the FCI.

It must announce these higher MSPs for the coming year so the farmers can plan accordingly. They can increasethe acreage for pulses cultivation and reduce the acreage for rice and wheat. The government must also announce that all imports of pulses shall remain banned from next year, giving farmers the required incentive and assurance for the future. With more pulses available at reasonable prices India’s nutritional quotient will also improve.

It will, consequently, also save on foreign exchange and improve farmer prosperity as well.

In effect, you cannot have an Atmanirbhar Bharat (self-sufficient India) or a Viksit Bharat (a prosperous India) without adopting the above strategies.

Effectively, India will have to teach its policy makers to respect Indian producers and not foreign farmers. Since Indian policy makers have not learnt these lessons, the matter has gone before the Supreme Court which has asked the government to explain its stand.

===============

Do view my latest podcast on the causes behind riots as in Nepal and Bangladesh, and the lessons for India. You can view it at https://youtu.be/AuiUlqS7UmA

———————–

And do watch our daily “News Behind the News” podcasts, streamed ‘live’ every morning, Monday through Friday, at 8:15 am IST. The latest can be found at https://www.youtube.com/live/JZhYUhmIGWY?si=kIngOeMbYkw8EyOT

===================

COMMENTS