Source: http://www.moneycontrol.com/news/business/economy/beware-the-merchant-charge-that-could-boost-gdp-spur-inflation-2459237.html

Will India’s GDP start soaring because of MDR?

RN Bhaskar — Dec 11, 2017 06:45 PM IST

It now appears that merchant discount rates –the rate paid by a merchant to a bank for providing debit card services — may become another major contributor to GDP numbers. Sounds unbelievable, no?

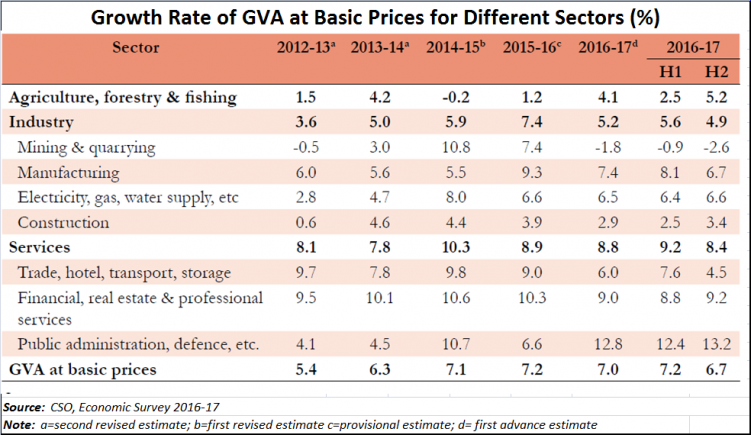

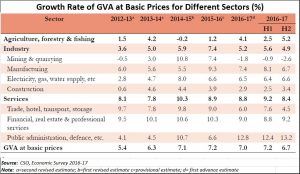

Conventionally, a country’s GDP usually soared because of goods manufactured and sold. This included agricultural as well as industrial produce. Then it began to include services as well. And as India’s GDP figures will show, the biggest contributor to its growth in GDP has been services. (See chart 1).

It now appears that merchant discount rates (MDRs) –the rate paid by a merchant to a bank for providing debit card services — may become another major contributor to GDP numbers. Sounds unbelievable, no?

It now appears that merchant discount rates (MDRs) –the rate paid by a merchant to a bank for providing debit card services — may become another major contributor to GDP numbers. Sounds unbelievable, no?

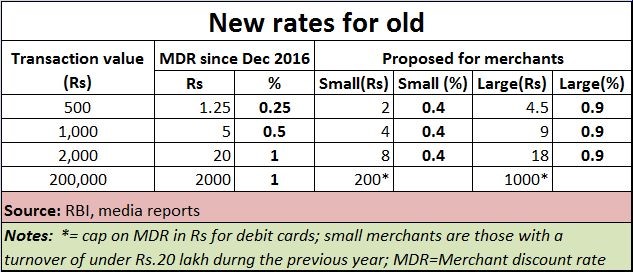

Last week, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) put forth a set of numbers which it said should be the new MDRs for debit card companies and e-payment players (credit card companies can still negotiate their own rates). This is because debit cards outnumber credit cards by a factor of 25:1. Reason? Debit cards can also be used as ATM cards. But till demonetisation took place, debit cards collectively handled only 42 percent of the value of transactions in India. Post demonetisation, this share is said to have swelled, but the RBI hasn’t come out with any new figures.

ALSO READ: Explainer: What is MDR and why are merchants not happy with it?

In fact, the RBI has intervened on MDRs at least three times during the past five years. It first announced, in June 28, 2012 (RBI/2011-12/625 — DPSS.CO.PD.No.2361/02.14.003/ 2011-12) that the MDRs would be 0.75 percent of the transaction amount for value up to Rs 2000/-; and 1 percent for transaction above Rs 2000/-. These rates were made effective from July 1, 2012.

Then, on December 16, 2016 (RBI/2016-17/184 –DPSS.CO.PD.No.1515/02.14.003/2016-17), it modified the MDR to 0.25 percent for transactions worth up to Rs 1000, and 0.5 percent for transactions worth Rs 1000 to Rs 2000. This thus revised an earlier circular asking banks to cap the MDR for debit card MDR to 0.75 percent for transactions of up to Rs 2000/-. For transactions worth over this figure the MDR was retained at 1 percent.

On December 6, 2017, the RBI announced (RBI/2017-18/105 — DPSS.CO.PD No. 1633/02.14.003/2017-18) that an MDR of 0.4 percent would apply to small merchants and 0.9 percent to large merchants. Small merchants were defined as those having a turnover of under Rs 20 lakh a year.

For QR based card transactions (Paytm and other such players) the MDR would be 0.3 and 0.8, respectively. The new rates come into effect from January 1, 2018.

For QR based card transactions (Paytm and other such players) the MDR would be 0.3 and 0.8, respectively. The new rates come into effect from January 1, 2018.

So is that good for India, or is that bad? It depends on your perspective. If you are an e-payment card issuer (Mastercard, VISA, Rupay etc) you would be happy. You can now collect more money from each merchant. Typically, MDR is not paid by customers. It is collected from merchants.

Since the merchants now have to pay a higher MDR, they are livid. They see some of their margins squeezed at a time when business itself has shrunk thanks to both demonetisation and GST.

But if you are an economist, you will see the surge in MDR as an added charge customers will have to bear. After all, no merchant pays the MDR from his pocket. He will eventually collect it from customers. As the government begins to push for e-payments, they see this as creating huge payment pressures on customers that they may not even be aware of.

In fact, e-payment players may end up making huge amounts of money which may exceed 5 percent of GDP (it could become as high as 20 percent of GDP).

Big money, bigger profits

Prima facie, the percentages look small, even reasonable. But that picture changes when one looks at the payments involved. And this is where one is convinced that the moolah in this e-payment sector could be so large that it could even dwarf other business opportunities. That could explain the surge in the number of e-payment players in the country. And since someone is bound to be making money, it is obvious that somebody will be paying up the costs. It then hits you that the costs for the common man are bound to soar, without his even becoming aware of it.

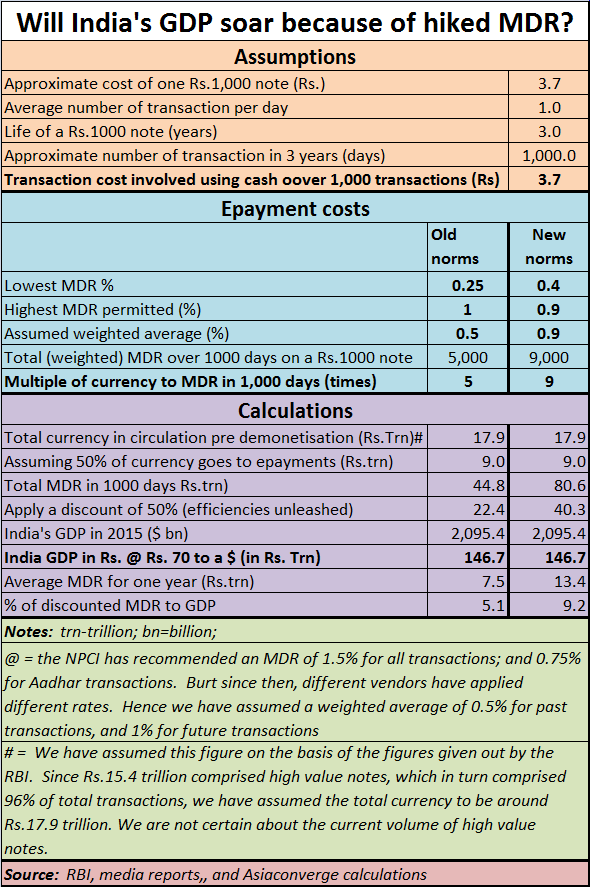

Once again, it is time to study the numbers carefully (See Chart 3).

First study the assumptions. All previous statements issued by the RBI suggest that each high value denomination note (Rs 500 or Rs 1,000) that was yanked out of circulation accounted for around 1 transaction per day. It is also known that the life span of each note was around 3 years (approximately 1,000 days), and that it cost the government around Rs.3.70 to print each high value note.

First study the assumptions. All previous statements issued by the RBI suggest that each high value denomination note (Rs 500 or Rs 1,000) that was yanked out of circulation accounted for around 1 transaction per day. It is also known that the life span of each note was around 3 years (approximately 1,000 days), and that it cost the government around Rs.3.70 to print each high value note.

Thus, assuming 1000 transactions over 1000 days before the Rs 1,000 note was finally phased out of circulation or destroyed, one can assume that the transaction cost for a Rs 1000 note was Rs 3.70 for a 1000 transactions. It is this that makes many believe that the cash economy was less harsh on small players in the country.

Now assume that you had an MDR of 0.5 percent (we have assumed this to be the weighted average for rates ranging from 0.25 percent to 0.9 percent). Suddenly the transaction cost for 1,000 transactions over 1000 days becomes Rs 5,000 (over a three-year period) or 5 times the value of the currency itself.

Now, when the RBI increases this MDR from a weighted average of 0.5 percent to 0.9 percent, it causes the transaction costs (MDR) to soar to Rs 9,000, or 9 times the value of the currency note itself.

Let’s play money

Let us then assume that only half the total value of currency notes in circulation (which during pre-demonetisation levels) were pegged at 17.9 trillion. Even though this data is over a year-old, we have continued to assume this figure, because other comprehensive figures are not available. Then, let us accept that digital transactions allow for better efficiency, and actually lower the total cost of ownership. We have thus applied a further 50 percent discount to the figures that we get after assuming only half the volume of currency in circulation.

Even then, when calculated against the MDR applicable, we get a whopping figure of Rs.22.4 trillion (Rs 22.4 lakh crore) using the old MDR, and an even more daunting figure of 40.3 trillion using the higher (proposed) MDRs.

Transaction costs alone account for 5.1 percent of India’s GDP (2015 figures) using the old MDR. They could swell to around 9.2 percent of India’s GDP if the new MDRs are taken into account.

You can further discount the figures in any which way you like, but the conclusion remains the same. Even without any increase in industrial production, or agricultural output, or even services, MDRs alone could cause the country’s GDP to grow – but at the cost of the common taxpayer. And as the share of digital services increases, expect the pie to become bigger and even more attractive for e-payment players.

Cautionary flags

This raises several questions.

First, will a surge in expenditure (through MDR charges) without any commensurate increase in production, trigger inflationary pressures (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2017/01/plicymakers-confront-epayment-complexities/)? Moreover with e-payment becoming more popular thanks to direct benefit transfer (DBT, Aadhaar), it means that e-payment players will make that much more money.

Second, will the enhanced MDR be further structured in such a manner to give banks a higher share of the MDR thus allowing them a source of income that could offset their (NPA caused) bleeding balance sheets?

Third, why is the government still dragging its feet over appointing a regulator for e-payments, given the large sums of payments involved (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2017/05/watal-report-and-the-war-over-epayment-and-digitisation/)? Will this lead to very big scams?

The potential for scams has already been highlighted in these columns. Some e-payment players have already entered into cozy deals with very large establishments to keep service charges off the books. A good example is the water department of the Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai (MCGM), which gives a receipt for the amount of the bills raised, but allows the service charges to be debited directly to the customer’s account. Thus, the bank shows one figure, which the receipts show another (http://www.moneycontrol.com/news/business/economy/how-off-the-book-e-payments-to-government-bodies-open-the-door-to-huge-scams-2382859.html). That means that auditors and regulators will not learn easily the amount of money that is being earned by e-payment players (and quasi government organisations will be the largest e-payment billing players in the country).

Ironically, when this practice was brought to the notice of the CVC (Central Vigilance Commission), it refused to look into this nature of billing, stating that this did not fall within the purview of its activities.

All these questions demand answers, because the implications affect transparency, cost to customers and the lopsided growth of businesses. Will the answers be forthcoming?

COMMENTS