R N Bhaskar

12 January 2015

In the first fortnight of December 2014, media reports talked about how poor policy-making had retarded investments of over Rs50,000 crore in the fertiliser industry.

Such reports were apparently based on a report by a leading credit rating agency stating that the Indian fertiliser industry’s import-dependence is expected to exceed 10 million tonnes annually in financial year 2017. This, it stated, could make the sector unattractive as it would impact industry’s profitability and credit profile.

Sometimes delays can be good

The truth is that, maybe, the delay in granting clearances for domestic fertilizer-capacity-expansion might not have been such a bad thing after all.

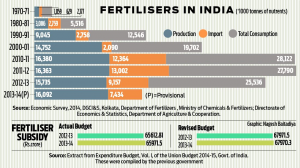

Do look at the table alongside. Domestic fertiliser production has galloped from just around 1 million tonnes of nutrients to well over 16 million tonnes in 2013-14. But imports, after peaking in 2011-12, actually declined.

This was certainly not because of any poor offtake by the Indian farming industry. One reason why imports declined could probably be because India had ended up importing too much, hence had a backlog of inventory. But there could be two other heart-warming reasons.

One could be that the government’s decision to release fertiliser-subsidy based on nutrients was actually paying off. Farmers were now getting better quality fertiliser, and hence needed less of this crop accelerator.

The other could be the rapid proliferation of micro-irrigation — thanks to the leadership and vision of Narendra Modi, while he was Chief Minister of Gujarat, and Chandrababu Naidu, when he was the Chief Minister of the erstwhile undivided Andhra Pradesh.

After all, micro-irrigation also permits the use of a technique known as fertigation — where the fertiliser is mixed with water in specified quantities and at specific stages of the life cycle of the crop. This ‘nourished’ water is then supplied through drip irrigation at the very roots of each plant (even for paddy, with amazing results). This way, the farmer does not scatter the fertiliser on his lands, which, in turn, ensures that there is little unused fertiliser which can then seep into the earth. That, unfortunately, causes leeching, and, consequently, degradation, of the soil.

So will domestic demand for fertilisers continue growing? Given the need for more food, it is bound to.

Not in India, but by India

But this does not have to be met through domestic production. This is because the increase in gas prices announced by the government last year might make domestic production of fertilisers a very expensive affair.

As pointed out by this newspaper in February 2013, the fertiliser industry itself accounts for 76.26 mmscmd (million standard cubic feet per day) or almost 27% of the total demand for gas. An increase of $3 per mmbtu will mean an additional outlay of $2.95 billion or almost Rs18,000 crore.

That is why it makes more sense for Indian urea producers to go to gas-producing countries, and produce fertilisers there. Industrialists like Kumar Mangalam Birla also spoke of such a strategy making immense sense.

It also explains why in October 2014, Ananth Kumar, Union minister for chemicals and fertilisers, announced that the government was actually examining the concept of a “reverse SEZ”, whereby a special economic zone could be set up in another country under a tripartite agreement involving that government (and maybe an investor from that country), India, and an Indian investor. It would allow India the right to import a specified part of the output at preferential rates for domestic consumption.

The minister identified countries like Iran being ideal for producing urea-based fertilisers, but also added Myanmar and Mozambique as well, as all these countries had an abundance of oil and gas resources. He might have also added Abu Dhabi’s Kizad (Khalifa Industrial Zone) which offers very attractive terms for gas users and for office rentals.

Not surprisingly, during the same month (October 2014) Russia offered India a 30% stake in Acron, the Russian potash manufacturer, along with a buyback agreement for exclusively supplying potash to India. This would be ideal for potash based fertilisers. This would be in addition to the existing (conventional) import agreement that Indian Potash Limited has with Uralkali, another potash manufacturing Russian company.

Will it be Russia?

In fact, Russia could be, strategically, the most important partner for India. It has an enormous bounty of natural resources, and a paucity of both capital and human resources (it has one of the lowest population densities in the world). A urea-producing plant in Russia could use Indian labour, thus protecting India from any perceived loss of jobs here.

At a time when Russia seeks to strengthen relations with India, this could be the moment for structuring reverse SEZs at extremely favourable terms for India. It would help reduce the cost of import, and would also allow India to consolidate its raw material sourcing, crucial to the future growth of the economy.

Moreover, as India moves toward direct benefit transfers (DBT) using Aadhaar-linked payment mechanisms, its annual fertiliser subsidy could reduce substantially from the current level of around Rs68,000 crore. A market-based pricing mechanism would compel existing fertiliser units to become more efficient in their operations (India’s urea-producing industry consumes more gas per tonne of output than some of the best fertiliser units overseas). Hitherto, since all costs are ‘pass-throughs’, there is little incentive to hone costs — either on account of laziness or even collusive accounting.

Both “reverse SEZs” and market-pricing of fertilisers — with targeted reimbursement of subsidies through DBT — could actually make this vital industry extremely vibrant and competitive. And this could — and ought to — happen without expanding production capacities within India.

The author is consulting editor with DNA.

Read the original article here.

Click here for more on India and its policies.

COMMENTS