http://www.freepressjournal.in/should-a-child-become-martyr-for-the-family/

Should a child become ‘martyr’ for the family?

— By | Dec 03, 2015 12:00 am

Child labour has never been an easy subject to deal with, especially when it comes to developing and under-developed countries. Its origins can be traced to impoverishment, and to life on the margins. And nothing explains the complexities involved than a study of what happened in Mumbai almost two decades ago. It is about how an NGO succeeded in its mission to protect children; and how success compelled them to abandon the project altogether; primarily because the world wouldn’t understand the relevance of what was being done.

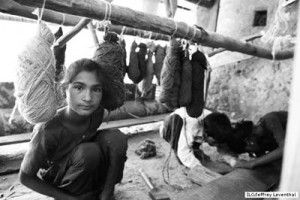

This story is based in the mid-1990s. This NGO decided to take a hard look at child labour in and around Mumbai. The NGO’s founders knew too well that child labour had its roots in poverty and helplessness. They were also painfully aware that often one child in the family was sent out to work. Most of these children came from the poorest and the most populous states in India – Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. Each morning one can see scores of children arriving in trains from these northern states into Mumbai, to be received by a caretaker, who would then pass them on to the owners of work units.

Each family had taken that agonising decision to send a child to the city to work so that the money he remitted back home would take care of the rest of the family, pay for the education of the siblings, and even provide the bare means to get his sisters married off.

Without the child going to work in a city, the rest of the family would be deprived of a means to get out of the rut they find themselves in. Moreover, even if the child did not go to work, there was little guarantee that he would be able to chalk out a career for himself on his own.

Finally, the NGO founders reached the conclusion that the benefits from child labour could actually outweigh the ills. But the working child had to be protected; in order to ensure that he would be left facing a dead-end when he crossed the age of 14 years, and could no longer find useful employment in a profession which only wanted children. They knew that the working child had to be provided with education and with skills for a life beyond childhood.

But how should working children get educated? The founders decided that the onus of education should lie with the owners of the work units where the children were employed.

So they put Plan A into action. They took some of their best girl volunteers to approach the unit owners in Mumbai to persuade them to allow the children working there to get educated. Since many of the children find employment in the zari (embroidery) industry – mostly located in and around Govandi, a suburb of Mumbai, which became the theatre where all the action would take place.

Most owners refused to do so. So plan B was embarked upon. The girls decided to stage a sit-out outside the zari units to compel the owners to submit to their demands that the children be educated. The zari owners were in a fix. If they used violence to push the girls out, it might become headline news and invite unwanted attention. They couldn’t approach the police either, because they were themselves in contravention of the provisions of the Child Labour (Prohibition and Regulation) (CLPR) Act, 1986.

One by one, the owners relented. So each day, for two hours after work, the social workers would gather the children and begin teaching them the alphabets, science, geography. But as the teaching began, they discovered that almost every child (all of them were males) had been subjected to sexual harassment.

So the girls began talking to the children about how to defend themselves. They taught the children the difference between “good touch” and “”bad touch”. They talked to them about awkward issues like masturbation, anal sex and other bestial ways of ‘buggery’. Most of all, they taught them of how to ward off unwanted advances – by merely screaming out loud, thus attracting the attention of elders and peers.

The plan appeared to work, till they discovered that some of the boys were too scared even to shout out in protest. The girls approached the owners, got their consent to finance a dormitory where the girls took the most vulnerable children into their care. Then they went about building community toilets so that the children could have some privacy for ablutions and bathing.

Their work was appreciated, and the NGO became a celebrity. Fame brought in money and gradually there were promises of more money, but only if they did not protect children. Under tremendous pressure from global agencies, the project was abandoned, even though Govandi still employs children. It remains the biggest zari production centre in western India. The NGO has grown to become one of the biggest in India and continues to do some amazing work for children and for the country. But the Govandi project has been forgotten.

That is why, even as the Parliament seeks to bring out amendments to the CLPR Act 1986, with the CLPR Amendment Bill of 2012, it must remember that the only way to eliminate child employment is through education and economic growth. That the onus of education must be with the employers, with a very strict and transparent compliance mechanism put in.

Without good education, the working children of today will become the unemployable youth of tomorrow. And without economic growth, child labour can never really be eliminated.

Now it is up to the policy makers.

COMMENTS