Source: http://www.moneycontrol.com/news/business/economy/the-ghostly-organisation-that-should-have-tranIs WDRA a functioning organisation?

Is WDRA a functioning organisation?

R.N.Bhaskar – Aug 07, 2017 01:36 PM IST

The Warehousing Development & Regulations Authority (WDRA) was meant to be a game changer in India. That is why it is perplexing to discover that so many of India’s legislators have chosen to ignore it for so long.

If one goes by appearances, the Warehousing Development & Regulations Authority (WDRA) (http://wdra.nic.in/ the new website is https://wdra.gov.in/ )is alive and kicking. Its website suggests that it is a vibrant and functioning organisation, and lists out the scope of its activities. It has a chairman, and several members (http://wdra.nic.in/Telephone%20Directory_English_24042017.pdf). At the same time, there is also an invitation for the post of a new chairman, and it has tenders that are being floated.

But the website does not give any details of what it has done for the past several years. It appears to be an organisation that has lofty intentions. The lack of information on its activities, therefore, remains a mystery.

Yet, there is no denying that the WDRA was meant to be a game changer in India. That is why it is perplexing to discover that so many of India’s legislators have chosen to ignore it for so long.

The apex court had ordered the government to provide all the grain free of cost to India’s poor rather than allow it to rot. The government dragged its feet. Its argument was that sending the grain to public distribution shops (PDS) would be a very expensive affair – costing around Rs.5,000 crore. That justification was obviously specious, because the government could have asked NGOs to pick up the non-warehoused grain free of cost on a as-is-where-is basis. The costs would have to be borne by the NGO concerned. People consuming the grain is a better proposition compared to letting it get devoured by rats or worms.

It is probable that the government did not want to stop the rotting of grain because it wanted – as is being alleged in several quarters – the evidence of the surplus grain to be destroyed by sun, wind, rain and pests. All indicators point to a devious practice by the Food Corporation of India (FCI) and several State Warehousing Corporations (SWCs) to make money illegally through grain procurement. The modus operandi appears to be procuring second-rate grain from well-connected farmers at first rate prices. The best way to erase evidence of the fraud is by allowing the evidence of the crop itself to disappear.

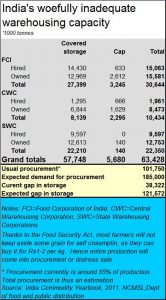

That could explain why the government continues to procure more grain than it can store. It procures over 150 million tonnes of grain a year even when its storage capacities are almost half that level (see table). Ideally, it should have sold the excess grain promptly on the spot market or even future markets. Even a sale as a lower price is better than losing all the value through rotting grain.

That could explain why the government continues to procure more grain than it can store. It procures over 150 million tonnes of grain a year even when its storage capacities are almost half that level (see table). Ideally, it should have sold the excess grain promptly on the spot market or even future markets. Even a sale as a lower price is better than losing all the value through rotting grain.

Whatever the reason, the WDRA finally came into existence in October 2010.

It remains one of the most important pieces of legislation in recent times, could potentially change the way agriculture and the trade surrounding it happens. Of course a lot will depend on the way in which many of the clauses of the WDRA get implemented, but the implications are mind-boggling.

There are several things the WDRA was meant to do which were missing earlier.

First, instead of the state procuring agricultural produce, the Act allowed for WDRA registered warehouses to step in. Farmers could walk into any warehouse (every district was expected to have such facilities) where such produce could be stored.

Second, the warehouse would have an assayer who would evaluate the quality of the produce and certify both the quality and the quantity and give the farmer a receipt.

Third this receipt would be recognized as a negotiable instrument, which the farmer could take to the bank and get money for his produce at prevailing spot market prices. Else the farmer could sell the produce directly through the commodity markets at current or future prices. The farmer also had the option of keeping the receipt with himself till he believed he could get better prices. In that case, the farmer would have to pay for the storage of the produce till the time it got sold.

Thus a small farmer, who was often ignored by the FCI or the SWCs could approach a warehouse with his meagre produce and get a receipt and encash it at his will. It would create a national market where a trader in, say, Orissa could purchase a few tonnes of grain from a farmer in Maharashtra through the commodity markets and collect the given quantity and quality from the local warehouse.

But all this pre-supposed some things.

> It presumes the existence of vibrant commodity exchanges for discovery of current and future prices.

> It presumes the existence of warehouses coming up registered by the WDRA. Currently, The National Commodities and Derivatives Exchange Ltd or NCDEX has a warehousing subsidiary known as National Collateral Management Services Ltd (NCMSL) and the Multi Commodity Exchange (MCX) has another subsidiary, National Bulk Handling Corporation (NBHC). Both have been setting up warehouses across the country. No consolidated data is available on the number of warehouses per district in India.

> It presumes that all FCI and SWC storage facilities would also come under the WDRA, and that any farmer who wanted to sell his produce could approach them. This would take away the ability of the FCI and any SWC to play favourites with powerful farmers and ignore small and weak growers (who have to then sell at distress prices). It assumed that all mandis (village markets) and APMCs (Agricultural Produce Market Committees) would also get linked to commodity exchanges so that any produce could be bought or sold at current or future prices.

That would ensure transparency, and give every farmer the ability to sell his produce at market prices, and not at distress prices. The farmer could also insulate himself against any potential crash in market prices by selling a part of his produce at prices that he thinks are good even before the crop gets harvested.

It now appears that the government has not ensured the fulfillment of the three preconditions given above. Thus even though the WDRA got notified in 2010, its office bearers have been using up taxpayers’ money with little to show by way of achievement.

In fact, had all this been done, the pulses crisis could have been avoided. In fact, if one goes through the list of commodities that WDRA is allowed to deal in, pulses are also covered. It is therefore surprising that the government did not use the WDRA route to help pulses farmers out.

A second list shows that WDRA has plans to cater to horticulture as well. Obviously, this is where the warehouse would ideally have to be a cold storage unit as well. It is not clear whether WDRA has moved into this direction, or whether such lists are only for public display. Emails and phone calls to WDRA officials drew a blank.

Maybe even WDRA officials think that the government is not serious about implementing the WDRA vision. That is understandable,. After all, haven’t the regulations been gathering dust since 2007? It is sad that even after the passage of so many years, there is so little progress for anyone to see. It is even tragic, because this was one surefire way to help reduce the shrillness of the cries relating to farm distress.

COMMENTS