India’s net FDI is a pointer to a deeper malaise

By RN Bhaskar

Image generated through https://deepai.org/machine-learning-model/text2img

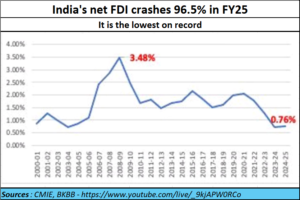

On May 23, 2025, media headlines announced (https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/business/india-business/indias-net-fdi-crashes-96-5-in-fy25-lowest-on-record/articleshow/121353121.cms) that India’s net FDI had plummeted by a shocking 96%. This was the lowest it had slipped. Some analysis was required, though the government maintained silence.

This was bolstered by data from the CMIE which showed how net FDI had moved over the years. The chart was worrying. Many media outlets have also commented on this development (https://www.youtube.com/live/_9kjAPW0RCo?si=Ln9Ke8bcHGvK_K4_)

This was bolstered by data from the CMIE which showed how net FDI had moved over the years. The chart was worrying. Many media outlets have also commented on this development (https://www.youtube.com/live/_9kjAPW0RCo?si=Ln9Ke8bcHGvK_K4_)

Sadly, when it comes to chest thumping, the government is extremely loud; and the cacophony can be annoying. But when it comes to explaining an awkward financial number, there is a studied silence.

To understand the situation better we tried to locate the required data from both the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (MOSPI). We drew a blank. Maybe, we were just too hopeful about MOSPI giving out the actual numbers. Even the RBI, which normally has such information readily available proved to be a difficult source.

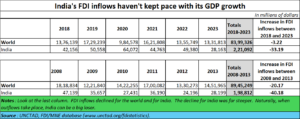

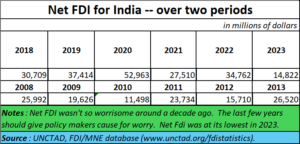

So, we went to United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). There we found (www.unctad.org/fdistatistics)) annual reports on Investment flows and picked up two volumes. One was the Investment report of 2014 and the other of 2024. The tables reproduced below are gleaned from these two volumes.

Here are the findings.

First look at the figure for 2013, It is roughly $28.2 billion. Now compare this with the figure for 2023 — the latest available. It stands at $28.16 bn. There is hardly any difference. It looks like a span that is lost in sound and fury signifying nothing. In fact, the FDI volume has declined.

Then look at the total FDI inflow during the 2008-2013 period. It stood at $1,99 bn.

Then look at the total for the 2018-2023 period. The number stands at $2.21 bn. There is not much improvement over the earlier period. It is as if time stood still for all these years.

The world did a bit better, though not appreciably so. It is quite possible that the financial meltdown of 2008 hurt it because it was more exposed to the turbulence than India was.

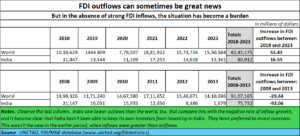

This type of flow takes place when Indians choose to invest overseas. It could be an acquisition, or an investment in a greenfield or brownfield project. Or it could be a way of taking money overseas where the government cannot touch it. The methods adopted are many. The transfer is legal. But it could be in a safer place given India’s penchant for raids and seizures. Not surprisingly, many millionaires are leaving India (https://asiaconverge.com/2023/06/india-stores-gold-overseas/). Whatever be the reason, the fact remains that money is going out faster from India, than the money coming in.

FDI outflows can be wonderful news, if they are accompanied by stronger inflows. But when FDI outflows accelerate, and inflows remain laggard, then we have a problem.

Consider first, the FDI outflow in 2013 which stood at $1.7 bn and compare it with the outflows in 2023. That was when outflows stood at $ 13.3 bn. Just observe the huge jump.

When total outflows for the two periods are considered, the figures remain almost at the same level. But earlier, inflows were strong. They aren’t strong now.

This has several implications. We can discuss them after looking at the status of net FDI.

Net FDI wasn’t so worrisome around a decade ago. The last few years should give policy makers cause for worry. are at their lowest during 2023.

Implications

There are two conclusions that can be drawn from the above numbers.

First, Indians prefer investing overseas than within India (https://asiaconverge.com/2024/12/money-is-flying-out-of-india/). This could be because investments overseas promise a good rate of return – better than those within India. But such investments also carry political and currency depreciation risks. Businessmen who believe that investments overseas are worth the effort, despite these twin risks must have a bleak picture about the investment climate in India.

Second, it means that foreigners do not want to invest in India. It is possible that they found investment in other countries more attractive. But with economic turbulence rocking the entire world, India promised to be a haven. Unfortunately, that is not the perspective overseas investors have.

Consider two problems overseas investors face.

First, India does not give them the comfort of either speedy and effective dispute resolution or international arbitration. That puts investors out on a limb. Once they have brought their money to India, they are subject to the insufferable judicial delays and changing regulations within India. Consider how the Devas Multimedia case (https://www.business-standard.com/podcast/current-affairs/what-is-the-story-of-the-antrix-devas-deal-122090900100_1.html) is still being fought – both within India and overseas. Devas has won favourable orders from international courts, but negative orders by Indian courts.

Secondly, many foreign investors are worried about India the overbearing law enforcement system that shoots first, and asks questions later. Bans, forced closures, threats of penalties, and newly crafted laws which are applicable retrospectively, have made investors extremely jittery about India.

Third, there is always the risk of rules being introduced with retrospective effect. There is little sanctity to either business rules, or even business policies.

As a result, investors seek to avoid India altogether.

Indian businesses too are at risk given the whimsical export and import rules announced by the government from time to time. At one time, agricultural exports are allowed, and another time they are banned.

Then there are policy makers that seek to allow milk and milk product imports, hurting the very foundations of India’s most successful agricultural produce (incidentally, milk has recently been taken out of the agricultural fold). Its contribution to the Indian GDP is greater than both rice and wheat put together (https://asiaconverge.com/2023/01/sodhis-resignation-has-dire-warnings-for-agriculture-and-milk/).

Conclusion

India’s policymakers need to reflect on the causes that make all this happen. The result is that notwithstanding claims about a Viksit Bharat – or a prosperous India – the country is losing money, goodwill and even friends (free subscription — https://bhaskarr.substack.com/p/india-is-losing-friends-influence)

=================

Do view my latest podcast on what makes the US what it is currently? You can view it at https://youtu.be/HbZicfRMSws

———————–

And do watch our daily “News Behind the News” podcasts, streamed ‘live’ every morning at 8:15 am IST. The latest can be found at https://www.youtube.com/live/R_13RigN4mU?si=xwIZMF1nUdD3QBYQ

——————————-

COMMENTS