India’s economy: three cheers for the small sector; only two for the large

Read Part I of this article here.

Nobody denies that India needs to think big. It needs large corporations that can stand up to the headwinds of global competition. It needs brands that the world recognises.

But the more one looks at numbers, the more one is compelled to believe that India’s backbone is its small enterprises. Yes, large firms matter. But there is an urgent need to be concerned about small-scale industries as well.

The first time the strength of India’s small and the medium got highlighted was in July 2003. That was when two scholars — Huang Yasheng, associate professor, Sloan School of Management at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Tarun Khanna, professor, Harvard Business School – began writing extensively about India and China.

They talked about how China excelled in creating a few large enterprises, while India’s strength was in the flourishing number of small and medium enterprises.

This was later elaborated on by a host of other analysts.

A couple of years ago, R Vaidyanathan, a professor from IIM-Bangalore, wrote his book India Uninc in praise of India’s micro sector. It is here that he discovers a vibrant unincorporated sector which the government often (and wrongly) refers to as the unorganised sector.

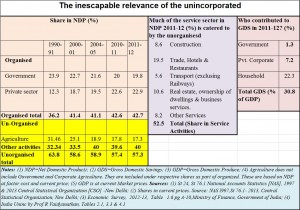

Unlike the private corporate sector, which accounts for a 30% share of India’s GDP, the unincorporated sector accounts for a bigger share of 40% (see chart).

Most of these “unincorporated” businesses (a term borrowed from are into services like construction, transport (excluding the railways), real estate and trade. But even here, the organised private sector accounts for just a 12.5% share, if one takes away the 40% that comes from the unincorporated sector.

Most of the workforce in this sector works on a contract basis, without the comfort of gratuity, medical reimbursement, or provident fund. That is why, the government’s move to provide pension and insurance to such people at very nominal rates of premium is a welcome step.

Most of the workforce in this sector works on a contract basis, without the comfort of gratuity, medical reimbursement, or provident fund. That is why, the government’s move to provide pension and insurance to such people at very nominal rates of premium is a welcome step.

Unlike the organised sector, this sector has to make private arrangements for capital — often paying at least 2% as interest per month. Bad debts are very few, unlike those faced by the nationalised banks.

And, as long as the politician does not intervene, even micro-lending financial institutions enjoy significantly higher debt recovery rates than nationalised banks. The moves of the government to bring them into the fold of inclusive banking is, therefore, extremely relevant – so long as they too are not spoilt by irresponsible political demands of loan waivers.

Hitherto, loans have been taken against gold, small assets, and personal standing in the community. Loans are repaid, because the collection mechanisms are far more demanding than the banks that politicians love to control. For proof, look at the way cooperative banks (mostly controlled by the political class) had to be hauled up by the RBI recently.

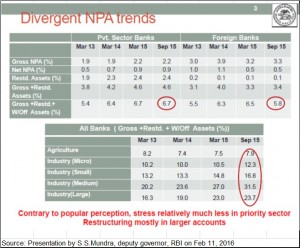

So understand how responsible the small sector has been, do look at the RBI chart alongside which shows this sector being responsible for the least amount of bad debts. The medium sector accounts for the largest share (31.5%) of bad and restructured debts (and this includes the likes of Bhushan steel and Kingfisher). The second largest defaulter is the large industries segment (23.7%). The smallest defaulter is the small segment with bad and restructured debts of 16.8%.

And yet, this is the sector that is often the victim of extortion – not by what is known as the conventional mafia, but by the government agencies – by sales tax inspectors, inspectors of the shops and establishments department, police, food and drug inspectors and employees at octroi-checkposts. They fleece this largely unprotected unincorporated sector.

That this sector survives, despite the exploitation, is testimony to its business savvy and innovative approach to business.

These are the unsung heroes of the Indian economy. India needs to pay more attention to them.

COMMENTS