https://www.freepressjournal.in/analysis/budget-2021-has-a-warped-view-of-indias-agri-economy

Animal husbandry was left with little in Budget 2021, though it deserved much more

RN Bhaskar – 8 February 2021

===============================

All the Budget 2021 articles can be found at http://www.asiaconverge.com/2021/02/budget-2021-series/

================================

To understand why Budget 2021 has a warped vision, one needs to look at two sectors –animal husbandry and banks.

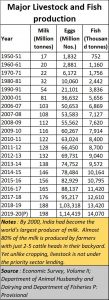

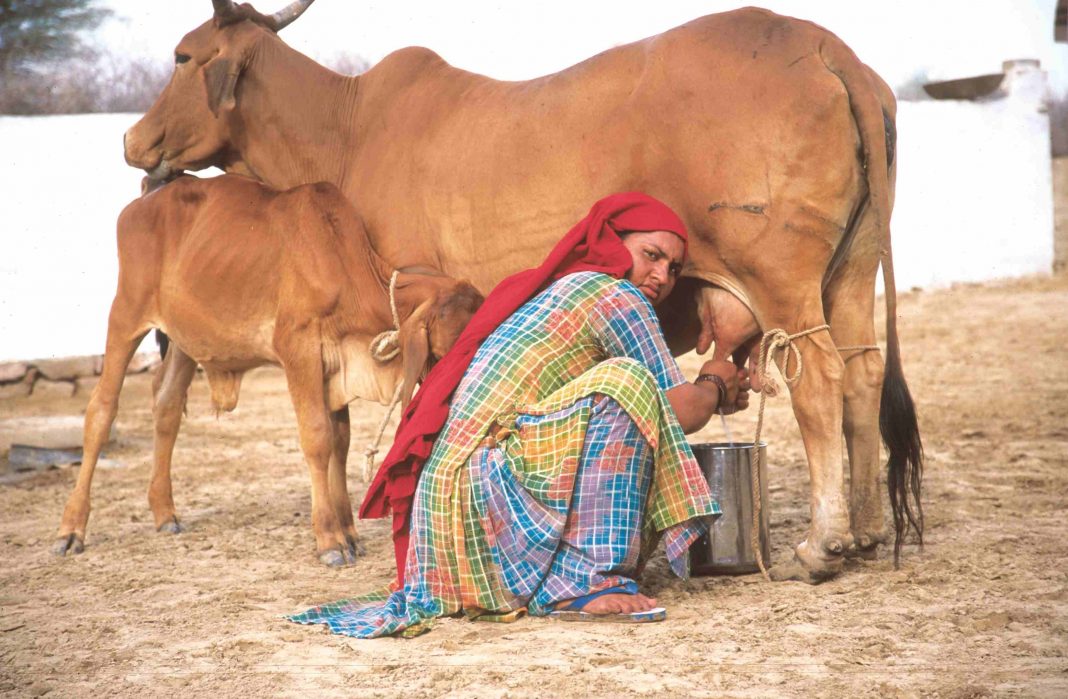

In this article we will focus only on animal husbandry. The reason for focusing on this sector – especially on dairy farming — is because it is a big employer and sustains millions of families. The entire animal husbandry sector contributes immensely to nutrition and empowers the most marginal of farmers and landless labourers. Milk alone accounts for around 100 million producers, most marginal, with no land.

The budget does make some provisions for this sector.

There is a second reason for focusing on the diary sector. It is one of the rare industries in India that has become the #1 player in the world. India is the lowest cost producer of milk as well.

There is a second reason for focusing on the diary sector. It is one of the rare industries in India that has become the #1 player in the world. India is the lowest cost producer of milk as well.

Even before the budget was announced the government had announced a Rs.15,000 crore package under the Atma Nirbhar Bharat Abhiyan for Animal Husbandry Infrastructure Development Fund. It was meant to support private investment in dairy processing, enable value addition and improved cattle feed infrastructure. But for an industry that has become the largest player in the world, and is a key contributor both to economic growth and mass nutrition, the offerings to the livestock sector have been extremely meagre, and the approach terribly flawed (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q4JY5YjWsBo).

Thus, the budget indirectly shows up the biases of the government against the milk producing community – more by what it does not say, but also by what it does.

Its strategic significance is also highlighted by the Economic Survey 2021. “Livestock sector is an important sub-sector of agriculture in the Indian economy. It grew at CAGR of 8.24 per cent during 2014-15 to 2018-19. As per the estimates of National Accounts Statistics (NAS) 2020, the contribution of livestock in total agriculture and allied sector GVA (at constant prices) has increased from 24.32 per cent (2014-15) to 28.63 per cent (2018-19). Livestock sector contributed 4.2 per cent of total GVA in 2018-19.”

Step motherly treatment

Yet, as RS Sodhi, managing director of the Gujarat Cooperative Milk Marketing Federation (GCMMF) – more popularly known by the brand of the product that it markets, namely AMUL — points out, animal husbandry has always got a step motherly treatment from the government lately, even though it is part of agriculture (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Yn0jU5rwMyc&feature=emb_logo). Sodhi made these remarks on behalf of the 100 million milk producers of India and even the livestock industry. His plea: “Treat milk or animal husbandry like any other agricultural crop.”

India’s planners haven’t been fair to the livestock sector, even though Budget 2021 does make some pious offerings to this sector. Fund allocations to the animal husbandry sector have been creased from Rs. 2,646 crore last year to Rs. 3,102 crore in this Budget. That represents an increase of 17%. But behind it lies a tale of discrimination.

Sodhi points out, the livestock sector deserves a lot more because of several reasons. First, it has many more marginalised players than the crop growing sector. Moreover, milk has remained an outperformer (see charts).

Secondly, since the dairy sector contributes to 27% of agricultural GDP it should have got at least a quarter of the fund allocation for agriculture. This 27% translates 5-6% of national GDP, because agriculture contributes to around 16% of national GDP (precise figures are never available, because the Indian government focusses more on GVA and not GDP). Yet, despite this importance, it gets access to just Rs.3,289 crore of funding from the government against Rs.1.46 lakh crore (Rs.2.4 lakh crore if one adds fertiliser subsidy as well) for the agriculture sector. Thus, it gets just 3% of funds for agriculture when its share ought to have been 27%.

Then there are other grievances. If a farmer has 50 acres of land and grows crops on it, all his income is exempt from income tax. But if a farmer has more than 10 cows, he is required to file income tax returns. Even GST (though this is outside the purview of the budget) has been unfair to this industry. Imported oils account for a GSt of just 5%. But a farmer who converts his surplus milk to ghee is slapped with a 12% GST. What Sodhi wants is one law for one sector.

Finally, animal husbandry is not considered to be part of priority sector lending – it does not figure in the RBI’s list of industries identified as the priority sector. This adversely affects its finances further.

The Budget has turned a blind eye to such requests for fair play.

Blind spot for bad faith?

The bad faith is visible elsewhere as well – though not strictly confined to the budget. On at least one occasion, the government almost short-sold the dairy sector, and the future of some 100 million farmers, by almost agreeing to permit New Zealand to export its milk products to India (the story and its horrendous implications can be read at http://www.asiaconverge.com/2019/08/indian-bureaucrats-almost-shortsold-the-milk-industry-at-fta-cpec-negotiations/). Huge protests followed, and the government backtracked.

A similar horror story could be unfolding once again, when India decides to import some 500,000 tonnes of malt barley (similar to corn or maize grown mostly by Bihar and MP) from Australia. Australia’s strategy is to use the open market in India to set off the losses that it will face due to steep Chinese tariffs (https://tfipost.com/2020/06/as-china-bans-australian-barley-india-opens-the-doors-for-aussies/). But since this deal was signed around May 2020, right in the midst of the pandemic, few noticed this development. Expect another protest on this issue soon, as it will affect maize prices in Bihar and MP.

But the biggest act of betrayal of milk producers came when the government decided to impose a ban on cattle slaughter in almost all BJP ruled states. There is a correlationship between the economic downturn in India and the collateral damage the ban on cattle slaughter has caused. The budget could have remedied some of it but hasn’t. We shall explain this a bit later.

Many states in East and North East India, and some states like Kerala and Goa refused to ban either cattle slaughter or the eating of beef. Thus while cow populations in these states did not suffer, other states where the slaughter ban cries became frenzied, the population of cows declined (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2018/05/cattle-slaughter-ban-missteps-may-factor-bjps-electoral-woes/). Census figures do not show the sharp decline, because the old cattle are still alive. But the number of milch cows has definitely declined.

But the frenzied mobs in some states – UP, Haryana, Rajasthan, MP and even Maharashtra – attached vehicles carrying cattle meat and demanded that the consignment be sent for testing to verify whether it was cow meat. Thus, a country, where forensics for humans is not easy to come by, was pushed into forensics for animals. And the meat, even if it came from buffaloes, was allowed to rot. Consequently, no trader was willing to transport even buffalo meat.

This is where the budget could have helped. If the government is keen on banning cattle meat, it is the job of the budget to compensate the farmer who used to get Rs.20,000 for each old cattle head. He used to add this money to borrowed money to purchase another milk producing cattle. Now he was at a loss. The refusal of the budget to compensate the farmer is both unfair and causes immense harm to the economy.

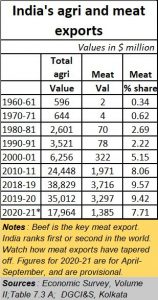

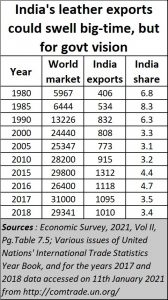

Remember, cattle hides are used by the leather industry which is a major foreign exchange earner (see table). These figures do not include the domestic market which is reckoned to be several times bigger.

So, you had 100 million milk producer families plus another 4.42 million families engaged in the leather trade. The slaughter ban affected both categories of employment and livelihood, with a spillover to other consumption industries as well.

India is the second largest producer of footwear, the second largest exporter of leather garments, the fifth largest exporter of leather goods and the third largest exporter of saddlery and harness items (https://www.makeinindia.com/sector/leather), And yet, claim many dealers in leather, the budget has left them unenthused (https://www.freepressjournal.in/business/budget-2021-fails-to-provide-hope-to-leather-market).

Thus, both milk and leather sectors were adversely affected. There is no relief for those who have been hurt financially. Some were hurt physically too, and cases against the accused continue to drag on.

It is both financially and politically irresponsible for any government to cause sectors to get hurt, with no compensation being paid in return. This is a major budgetary and policy failing. Unfortunately, few people speak about it. True, there are people who claim that even old cattle can be taken care of profitably. Let the budget provide for transfer of such cattle to such claimants. But first compensate the farmers. After that if the claimants make huge profit from their theories and practice, great! Hats off to them.

There is a third casualty. The cattle slaughter bans hurt meat exports as well. Much of the meat exported is beef – often carabeef (beef from buffaloes). When it comes  to carabeef, India is the world’s largest exporter (because few other countries rear buffaloes). When it comes to all types of beef, India is invariably in the first two places, though in the last few years, thanks to the cattle slaughter ban, it may have slipped a few notches lower.

to carabeef, India is the world’s largest exporter (because few other countries rear buffaloes). When it comes to all types of beef, India is invariably in the first two places, though in the last few years, thanks to the cattle slaughter ban, it may have slipped a few notches lower.

Indian beef is in demand because of the quality of the meat. In most countries’ cattle must be reared for meat. In India, meat is a by-product of the milk industry. It is not fed food accelerators or offal. Hence the meat is considered to be better than that coming from other countries.

According to the Economic Survey 2021, “The shares of the commodities such as buffalo meat and raw cotton in total agricultural export value have, however, declined during the period.”

But it also admits that “According to FAOSTAT production data (2019), India ranks 5th in meat production in the world. Meat production in the country has increased from 6.7 million tonnes in 2014-15 to 8.6 million tonnes in 2019-20*. The annual growth rate of meat production was 5.98 per cent in 2019-20 (April-September, provisional figures).”

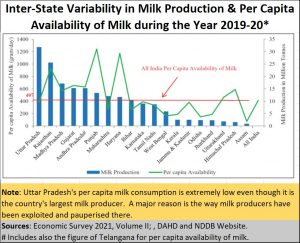

Finally, there is another angle which the budget has not looked at. It is the callousness of some states which do not even care to pay farmers a fair price for milk. A fair price should not be difficult to discover, because the price leaders are Gujarat cooperatives which were nurtured by India’s Milk Man, Dr. Verghese Kurien (Game India — http://www.asiaconverge.com/2019/02/game-india-seven-strategic-advantages-can-steer-india-wealth/). .

Yet India’s largest milk producing state, Uttar Pradesh continues to pay farmers only Rs.18 er litre against 26-40 a litre by most other progressive states. Even Maharashtra s milk processors, which tried to pay a lower amount, were compelled (by both former chief minister Fadnavis and NDDB’s milk procurement in the  Vidarbha region) to pay farmers Rs.26 a litre. But the Union government has not leaned on the UP-state government to give farmers a fair deal, even though it is a BJP state.

Vidarbha region) to pay farmers Rs.26 a litre. But the Union government has not leaned on the UP-state government to give farmers a fair deal, even though it is a BJP state.

That is again where the budget should have come in. It could have created financial disincentives for traders procuring milk from non-cooperative sources. That would have propelled the state to introduce milk cooperatives under the rules that NDDB has created, and thus ensure that farmers get paid a better price. This concern for UP’s distressed milk producers has not even been addressed by the three farm legislations that the government has been trying to defend (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2020/12/farmer-agitations-fueled-by-corruption-politics-and-power/). That should have provided the Budget makers to introduce budgetary provisions and financial incentives and disincentives to protect farmer interests.

As the chart above shows, even though UP is India’s largest milk producing state, its per capita milk availability is poor. It remains one of the most impoverished states in India, and the budget should have addressed ways to pull up this state rather than allow it to live of doles and grants.

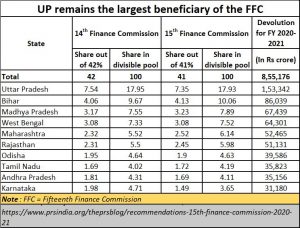

It is also not surprising, that the latest report of the 15th Finance Commission also confirms UP being the largest recipient of fund transfers from the centre.

It is also not surprising, that the latest report of the 15th Finance Commission also confirms UP being the largest recipient of fund transfers from the centre.

This is an off the Budget management of funds, and it is the job of the Budget to ensure that states stand on their own feet and not live on doles and grants, which in turn encourages the creation of rent-a-crowd mobs.

In many ways, UP has managed to wrest funds from the government under one pretext or another (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2020/08/government-plunder-productive-states-in-india/). That is not the problem. If a state receives funds, it must also ensure the upliftment of its citizens. The little data that is available on the way it has treated milk producers is appalling. The Budget should have introduced some fiscal measures to bring in greater transparency, and better welfare for the citizens for whom the budget papers are presented to the parliament each year.

If only the Budget could have shown greater concern for the marginalised — especially by the acts of commission and omission of several policy makers when it comes to livestock and the people who rear them – that would have been wonderful. Another opportunity missed. More pain ahead.

COMMENTS