R N Bhaskar

20 April 2015

Private faces in public places

Are wiser and nicer

Than public faces in private places

—WH Auden

Can religion influence business? Yes indeed! A good indicator is the decline in cow population in Gujarat and Uttar Pradesh. Today, both states have more buffaloes than cows — UP’s cow population is less than 39% of total cattle in that state. Gujarat sports a higher figure of 49%, but this number could tumble further. Sadly, these two states legendarily harboured Lord Krishna, the cowherd who is worshipped as a god by the Hindus.

There is yet another equally compelling example. It relates to the manner in which the Jain community has successfully persuaded many of its entrepreneurs to stay away from businesses that its religious leaders consider to be unacceptable. Go to any chemist/pharmacy in Mumbai where the proprietor is a Jain. Chances are that he will not stock insecticides, including mosquito sprays. The reason: the Jains are against wanton killing.

But, just try asking them if they think antibiotics (that a pharmacy must dispense) don’t kill bacteria? You will be greeted with a furious, yet stony, silence, because you have the temerity to mock their faith. There is a point beyond which answers are not required, justifications not needed. That is when faith is absolute. Or take the case of Raymond Woollen (now rechristened Raymond Limited) managed by a section of the Singhania family. Raymond is acknowledged to be the finest producer of woollen garments and worsted fabrics in the country. The quality of its products is acknowledged to be among the best worldwide.

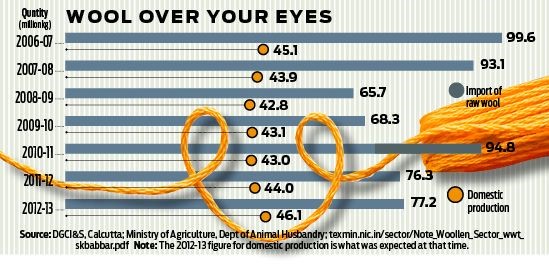

However, even this company had to abandon its dream project in the 1980s. During the Seventies, the Singhanias hit upon a great strategy of consolidating Raymond’s position in the field of woollens by actually improving the quality of wool obtained from Indian sheep. As any student will tell you, most of the wool produced in India is not of the best quality, and often goes into making ‘shoddy’ blankets. Much of the quality wool is imported (see table) from countries like Australia and New Zealand which produce ‘merino’ wool.

The Singhanias wanted to cross-breed Merinos with Indian sheep and produce first grade wool in India itself. To do this, the company set up a subsidiary unit and started a large sheep farm in Dhule (Maharashtra).

Setting up such a venture is not easy. It needs very patient capital (returns come in after decades), vision, and a guaranteed buy-back of the wool produced. The promoters of Raymond could meet all the three conditions. Such a venture would have allowed Raymond to consolidate its position even further in the world of woollens and worsted fabrics and garments.

The objectives of this company were immensely laudable. They included (i) producing wool of suitable quality for worsted/woollen/carpet and allied sectors, (ii) multiplying such units at locations convenient to sheep raising, (iii) importing, breeding, selling, exporting sheep and sheep products, (iv) assisting the government in taking up cross-breeding programme for upgradation of local sheep through regular supply of acclimatised exotic/cross-bred/local rams, and (v) establishing, extending and/or reorganising sheep and wool extension centres in collaboration with state governments for improving the quality and increasing the production of wool per sheep which would assist sheep breeders in enhancing their return per sheep to make sheep rearing a profitable rural occupation, encouraging mixed farming, and promoting sale of wool and woollen goods in domestic and international markets.

The project did extremely well, and the Singhanias basked in the glory of their achievements. The Dhule sheep farm became a centre for excellence in India. By 1977, Raymond was the first in the country to introduce Embryo Transfer for sheep.

Then suddenly the farm shut shop. The entire stock of sheep was handed over to the state-owned Maharashtra Sheep Development Corporation.

The official version is that the Dhule farm experienced a strike which culminated in violence and theft. The company, therefore, decided to discontinue the sheep development project to avoid further loss of life and property.

The private reason, as gleaned from people close to the top management, is that the Singhanias were asked by their religious leaders to explain what would happen to the sheep after they had lived past their productive years. When the Singhanias said that the sheep would be sold to traders, they were asked “for what?” There was no further need for answers.

The religious elders advised the family to quit the business. The project is not spoken of any more. And India’s wool imports continue unabated.

Fortunately, family had the good sense to salvage some of the knowledge it had already gained and mastered in the field of development and propagation of embryo transplantation techniques. It decided to apply these skills for both upgradation and breeding of high milk-yielding cattle instead. This is because cows are revered by the Jains as well.

By doing this, the family was using technology to reduce the possibility of cattle slaughter through sex determination so that only female calves would be produced. Quite the opposite of what many of us do in India — abort the female and mollycoddle the male.

Over the years, it has successfully ensured the birth of thousands of embryo transfer lambs and hundreds of embryo transfer calves. It has produced quality bulls through its embryo transfer technology for semen production. The semen is subsequently frozen for insemination for producing calves from these sex-determined embryos. Today, the Raymond Embryo Research Centre has gained global recognition for its work. It is currently the only government-accredited embryo transfer laboratory in India.

So is the influence of religion over business good or bad? That’s a difficult question. The best answer is that it is a personal choice that each businessperson will have to make for himself.

And how different is the Jain influence over business from the Hindu approach? Significantly different. The Jains pursue their religious objectives privately, without asking for state intervention. Religion remains, and must remain, a private face in any public place.

Unfortunately, when beliefs become fundamentalist, they become public faces in a private places. That can be both obnoxious and worrisome.

The author is consulting editor with DNA.

Read the original article here.

Click here to read more about India and its policies.

COMMENTS