http://www.freepressjournal.in/business/production-targets-met-agri-management-next-step-for-mp-narendra-dhandre-dgm-netafim/1300052

Netafim has big plans for Madhya Pradesh

— By | Jun 20, 2018

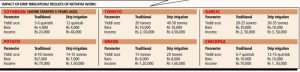

Increasing the yield of agricultural produce and using water effectively are the need of the hour for farmers in Madhya Pradesh (as is the case for the rest of the country). Despite the increase in production, improvement of yields has not been up to the mark. However, drip irrigation will be vital here, said Narendra Dhandre, DGM, Netafim. While speaking to Pankaj Joshi and R N Bhaskar, Dhandre explains in detail about drip irrigation and its advantages.

Excerpts:

How do you see Madhya Pradesh (MP) as a market for agriculture?

In terms of agriculture MP is a god-gifted region, with 11 diverse climatic zones, soil types and supportive size of water availability. About 35 per cent area in MP is irrigated against 18 per cent in state like Maharashtra where traditionally most of the water supply goes to sugarcane and large areas are left with water scarcity.

Today, MP has spread irrigation. It shows in the crop yield increases by and large. It now needs to have agri-management in place. That means, among other things, a focus on technologies like drip irrigation is needed. Beyond that, the enhancement of food processing infrastructure is needed which should be in line with the enhanced agri-output. Today, the government focus is limited. They are trying to set up agri-processing hubs lately like an orange-dedicated hub in Agar Malwa.

Another area where focus is needed is warehousing, where limited availability hits not only cultivators but even the government. Last year, the state government bought onions at Rs 8 per kg but due to lack of storage had to sell them off at Rs 4 per kg.

The price, immediately after this supply was absorbed by stronger hands, went to Rs 20 per kg. Overall, MP needs cold chain – both in storage and transportation.

Lastly, it is necessary to institutionalise education of farmers, to enable them to think strategically about their activity – what to sow and why, how to manage the process right from inputs to harvest cycles and post-harvest output management.

Are yields the key benefit driver?

Are yields the key benefit driver?

Not entirely. The second impact is the lower water utilisation. This saving has twofold impact—first is the cost and then you have to cope with different scenarios related to water. If water is not adequately available in the final phase of cultivation, there there is loss during harvesting. Drip irrigation is an advantage in such situations.

Another aspect is that with drip irrigation the harvesting part of the crop cycle can be extended to more harvests in the same sown area. Alternatively, harvesting time can be brought forward, so the farmer’s produce does not come to the market at the same time as everyone else. Both scenarios enable the farmer to earn more.

Where do you stand as a company today?

All India coverage of Netafim is more than 8 lakh hectares. In Gujarat our total coverage would be in the range of 2.5 lakh hectares and we are currently growing our coverage by 30,000 hectares annually. In Maharashtra likewise our total coverage is 2.5 lakh hectares with an annual growth of around 20,000. In the states of Telangana and Andhra Pradesh we have got aggregate coverage of 1 lakh hectares. In Chhattisgarh till date we have managed 25,000 hectares and in Madhya Pradesh it is around 20,000. These are our main activity states.

What are the on-ground issues that Netafim faces?

Drip irrigation is given a subsidy of 50 per cent by the state government. Normally, since the farmer lacks the ability to collect the subsidy amount, it is the drip irrigation company that provides the system at a subsidised price, and collects the subsidy amount from the government concerned. However, unlike Gujarat, where the subsidy amount was reimbursed to the company only after ascertaining that it had hand-held the farmer for a year at least, such extension services are not conditional to the reimbursement of the drip system subsidy.

One reason could be that the state horticulture department faces a manpower crunch. The department strength is around 250 whereas the requirement is 450.

Now we look at the issues which the cultivator faces. First, certain climatic modifications have seen changes in temperature and rainfall patters, which have started to impact crop yields. Another big factor is remuneration – procurement rates have moved downwards in the past two years. For instance, soya quintal rates in 2013 were Rs 4,000 and the following year they crashed to Rs 2,500. Chickpea rates last year were Rs 100 per kg and this year are Rs 40-45 per kg.

The upshot of this is that 80 per cent farmers today are holding stocks of garlic, onion and chickpea, waiting for better realisations. The holding is not in dedicated, well-structured warehouses, but in stockyards or open storage in their own homes, leaving them vulnerable to crop losses due to weather, rodents, livestock and other factors.

Rates today are controlled by large private players in procurement. Even if the agri-park infrastructure comes up, this situation will not change.

There is probably a need for an NDDB-style procurement mechanism which assures processors of steady output, cultivators of sustainable prices, consumers of decent supply and variety of processed foods at proper pricing.

COMMENTS