https://www.moneycontrol.com/news/india/comment-how-politics-is-playing-havoc-with-carbon-control-imperatives-2691271.html

Elections and carbon control imperatives

Prudence is a good thing to be taught in schools, but not something that is cherished and championed during election season.

Election seasons are not always the best of times for mulling over desired policy changes. That is when most lawmakers are focused on what could help them win elections. They care less about what could make the country stronger (or less weak). This is not true just of the current ruling party, but of the opposition as well.

In terms of priorities, survival instincts prevail over economic sense.

That could explain why even a compelling concept like rooftop solar which can create over 80 million jobs has been kept aside (http://www.moneycontrol.com/news/business/dear-pm-modi-heres-how-bureaucrats-are-planning-to-scuttle-your-rooftop-solar-employment-plans-2468501.html). The last thing that policymakers want is a concept that could compel them to disband the current power grids managed and controlled by state governments and the Centre. It is these power distribution networks that help governments play the role of patron saint and godfather. Politicians love the role of dispensing favours – whether it be higher support prices to farmers, or free or subsidised power to the largest vote banks.

Prudence is a good thing to be taught in schools, but not something that is cherished and championed during election season. This is true both for India and the rest of the world. The only difference is that in most parts of the developed world, the balance of checks and controls is zealously guarded by institutions that have not been battered and bruised as in India. Hence, the ability of politicians to causer immense economic harm can be severely curtailed.

Prudence is a good thing to be taught in schools, but not something that is cherished and championed during election season. This is true both for India and the rest of the world. The only difference is that in most parts of the developed world, the balance of checks and controls is zealously guarded by institutions that have not been battered and bruised as in India. Hence, the ability of politicians to causer immense economic harm can be severely curtailed.

But then considering what is happening to the US and to multilateralism, it goes to show that even developed countries can sometimes become captive to a demagogue who can ignore institutional restraints.

Economic sense

Coming back to environment, there are some points that the OECD would have us bear in mind.

For starters, almost everyone recognises the need for better infrastructure in the world. Better roads mean less fuel wastage. Better drinking water, means fewer deaths and reduced health complications. This is what a recent OECD report tries to point out (Investing in Climate, Investing in Growth, OECD, 2017)

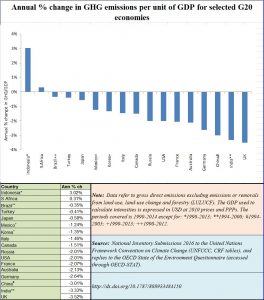

But what is seldom known is that for most countries, increase in GDP invariably results in reduced carbon emissions. For instance, better roads translate into lower automobile emissions. This is borne out by OECD findings (see chart).

But what is seldom known is that for most countries, increase in GDP invariably results in reduced carbon emissions. For instance, better roads translate into lower automobile emissions. This is borne out by OECD findings (see chart).

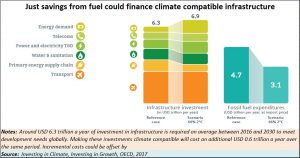

Similarly, what is also not factored in usually is that all costs involved in providing climate-friendly policies actually pay for themselves. True, making infrastructure compatible with climate  change (for instance electric vehicles instead of hydro-carbon powered vehicles and microgrids linked to rooftop solar, or the use of LED bulbs instead of the conventional lights) cost money. But the additional expenditure is easily neutralised by the sheer savings in fuel costs (see chart). As the OECD report puts it, “Climate-compatible infrastructure investment needs are only 10% higher and can be offset with fuel savings . . . Around USD 6.3 trillion a year of investment in infrastructure is required on average between 2016 and 2030 to meet development needs globally. Making these investments climate compatible will cost an additional USD 0.6 trillion a year over the same period. Incremental costs could be offset by fuel savings of up to USD 1.6 trillion per year through 2030.”

change (for instance electric vehicles instead of hydro-carbon powered vehicles and microgrids linked to rooftop solar, or the use of LED bulbs instead of the conventional lights) cost money. But the additional expenditure is easily neutralised by the sheer savings in fuel costs (see chart). As the OECD report puts it, “Climate-compatible infrastructure investment needs are only 10% higher and can be offset with fuel savings . . . Around USD 6.3 trillion a year of investment in infrastructure is required on average between 2016 and 2030 to meet development needs globally. Making these investments climate compatible will cost an additional USD 0.6 trillion a year over the same period. Incremental costs could be offset by fuel savings of up to USD 1.6 trillion per year through 2030.”

Three compulsions

But don’t expect the Indian government to begin thinking this way. There are three reasons that suggest that such pious thoughts won’t cut any ice with politicians right now.

The first, as discussed above, is the penchant for playing godfather.

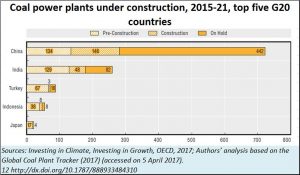

The second is the inability of politicians and powerful businessmen to move away from coal at the moment.

After all, a great deal of money has been invested in coal. This was more so a few years ago when investors rushed to win — through a transparent auction process — the rights to mine coal, India’s Supreme Court had just banned preferential allotment of such mines to politically aligned parties.

There is also the issue of too many people who are currently employed with the coal industry. Government-owned Coal India is a major employer, and it wouldn’t make sense for the government to put powerful coal unions on the warpath. Nor would it make sense to stop the political funding that takes place through illegal mining (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2017/04/illegal-mining-and-political-funding/).

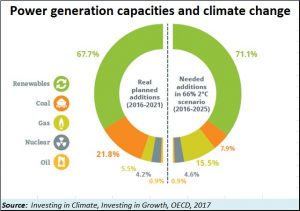

Thus, even though experts at OECD would like to see India reduce its dependence on coal (see chart), chances are that this would get phased out over a couple of decades.

Thus, even though experts at OECD would like to see India reduce its dependence on coal (see chart), chances are that this would get phased out over a couple of decades.

The third is the unwillingness on the part of the politician to relinquish some control on agriculture. This is despite the fact that agriculture needs to change quickly because it could be the worst affected by climate change.

After all, reforming agriculture would require the abolition of the deeply flawed Food Corporation of India (FCI). Moreover, the Warehousing Development Regulations Act (WDRA) has been lying toothless and forgotten (http://www.moneycontrol.com/news/business/economy/the-ghostly-organisation-that-should-have-transformed-indias-food-warehouses-2352429.html). Obviously, strengthening the WDRA would require weakening or even dismantling the FCI, No politician wants to do this as yet (but more on this later).

As the OECD report points out, the “negative impacts of climate change on yields of crops such as wheat and maize have been more common than positive impacts. Crop yields are projected to increase by 2050, but by less than would otherwise be the case. . . Under a very high emissions scenario . . . climate change could increase the prices of major grains by 5-30%, leading to increases in the proportion of people suffering from malnutrition in South- and Southeast Asia, Middle East and North Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa. Without adaptation, aggregate production losses are expected for wheat, rice and maize for 2°C of local warming. . . . This applies to both temperate and tropical regions and increases over the century.”

The alternatives

So what are the alternatives before India?

One can envisage three possibilities.

#1: Wiser counsel prevails once elections are done with, and the process of reform is taken up very seriously. But that might end up as a pious hope that many might cherish for a long time. Chances are that the mandates will not be as clear cut as during the 2014 elections. And irrespective of what the outcomes are, the desire to let patronage and political funding continue will be powerful motivators instead of economic sense.

#2: Conditions in India are likely to fester. This possibility could also be ruled out because the financial space that the government enjoyed till now is fast disappearing. What happened to India in 1990 when its coffers ran dry is likely to happen once again, because banks will be unwilling to lend aggressively for a few more years. Reason one: the NPAs (non-performing assets) will hobble them. Reason two: with more politicians egging on farmers demanding loan writeoffs, many banks will stay away from extending farm loans. Thus much of farmer advances will now come from micro-finance companies and NBFCs (non-banking financing companies) or from moneylenders at substantially higher interest costs. Expect discontentment in the farm sector to continue, compelling politicians to think of new measures. But with the fiscal elbow-room diminishing, and with the need to remain relevant to electoral communities, the economic wounds of India may not be allowed to fester for too long.

#3: Events will move so quickly – thanks to disruption on the energy and mobility fronts (https://www.moneycontrol.com/news/business/companies/interview-tata-power-ceo-praveer-sinha-says-best-positioned-to-deal-with-coming-disruptions-in-energy-markets-2582025.html) — that new policies will have to be crafted quickly to salvage a rapidly deteriorating situation. Expect policymakers to be dragged, kicking and screaming, to the policy tables immediately after elections are over, to craft out new policies. Some of them will be influenced by powerful lenders, some by multilateral bodies like the AIIB, the IMF, ADB and the OECD. But much of it will come from the sense of self-preservation that is very strong among politicians.

India may still see good policies emerging — that are sound both for the environment and the economy.

COMMENTS