https://www.firstpost.com/business/maharashtra-milk-crisis-farmers-need-to-get-a-fair-price-but-subsidy-is-not-the-solution-4775471.html

Is the milk in Maharashtra curdling?

RN Bhaskar Jul 19, 2018

Mahararashtra’s milk producers (actually supposed to be farmers who own cattle to produce milk) are on the warpath. They are being led by Raju Shetti, member of Parliament, and founder of the Swabhimani Shetkari Sanghtana. He says that the state government must give farmers a subsidy of Rs.6 per litre of milk that they produce and sell within Maharashtra. He says that the farmers have a right to get a far price for the milk they produce.

Shetti is right about the need for farmers getting a fair price for the milk they produce. But he is wrong to demand a subsidy of Rs.6 (even Re.1 would be wrong in principle) for milk producers.

In fact, all the politicians who have backed this demand – from the Congress, the NCP and even surprisingly from the Shiv Sena — are also wrong in making this demand.

The genesis

To understand the current milk price crisis, it is important to go back to history. The farmers who have been spilling milk on the highway are trying to invoke the spirit of the milk agitation in Gujarat – supported by Sardar Vallabhai Patel, Morajee Desai and Tribhuvandas Kishibhai Patel (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tribhuvandas_Kishibhai_Patel). They don’t realise the farce behind this re-enactment.

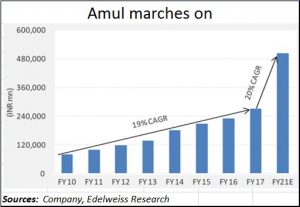

When Gujarat’s milk cooperative movement was launched in the 1950s, it was Tribhuvandas Patel who identified Verghese Kurien as the right person to nurture the milk cooperative movement, which later came to be known as the white revolution (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2016/03/significance-of-the-dairy-industry/). It was Verghese who crafted policies that actually nudged India into becoming the largest producer of milk in the world. Today, thanks to him the Amul brand is the largest processed food brand in Asia (see chart)

Kurien could do this because he believed that no amount of farm production would be sustainable unless the farmers got a decent return for their produce. And since much of dairy farming was done by small farmers who had just 2-10 cows in their backyard, he believed that the India strategy would need to be focussed on production by the masses and not mass production.

In order to ensure that the farmer got a decent price for the milk he produced, it was imperative to benchmark a percentage of market price that should go to the farmer. And this is where the Kurien genius lay.

While the world over, the farmer gets only one-third of the market price for his produce – with one third going to the processor, and another third got the marketing distribution network — Kurien insisted that at least 70% of the market price of milk should go to the farmer. He later fine-tuned this further and ensured that the farmers in his cooperatives got 80% (and at times 85% if bonus was included) of the market price for milk.

Overnight, Kurien had changed the global milk structure. He ensured that all procurement, processing, marketing, distribution and cash collection was done within 20% of the market price for milk. In order to do this, he introduced a high degree of technology, accountability, financial transparency, and more imp0ortantly a system that did not allow politicians or bureaucrats to get a paisa of what was legitimately deserved by farmers.

Overnight, Kurien had changed the global milk structure. He ensured that all procurement, processing, marketing, distribution and cash collection was done within 20% of the market price for milk. In order to do this, he introduced a high degree of technology, accountability, financial transparency, and more imp0ortantly a system that did not allow politicians or bureaucrats to get a paisa of what was legitimately deserved by farmers.

That is one of the key reasons why even today politicians and bureaucrats hate Kurien even while making public statements praising him. Kurien, incidentally, has not been nominated for the Bharat Ratna, even though he was responsible for transforming the milk industry in India and the world.

As for Kurien, his vision required several things to be done – which were thankfully put into place thanks to the support of former prime minister Lal Bahadur Shastri. First, was control of the NDDB. This was to ensure that soft imports would never be allowed to depress domestic prices of milk. As long as Kurien was alive, he made NDDB the agency for taking in all imports and even gifts and aid – milk powder, ghee or any other milk produce. Later, gradually, this was released into the market at market prices. This way, market prices never got depressed. The difference in prices (imported, gifted and the sale price) was collected by NDDB for market development. Had this model been adopted by the government – both past and present — , the pulses imports would not have created farmer distress (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2017/05/how-pulses-imports-drove-domestic-growers-to-the-ground/).

As for Kurien, his vision required several things to be done – which were thankfully put into place thanks to the support of former prime minister Lal Bahadur Shastri. First, was control of the NDDB. This was to ensure that soft imports would never be allowed to depress domestic prices of milk. As long as Kurien was alive, he made NDDB the agency for taking in all imports and even gifts and aid – milk powder, ghee or any other milk produce. Later, gradually, this was released into the market at market prices. This way, market prices never got depressed. The difference in prices (imported, gifted and the sale price) was collected by NDDB for market development. Had this model been adopted by the government – both past and present — , the pulses imports would not have created farmer distress (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2017/05/how-pulses-imports-drove-domestic-growers-to-the-ground/).

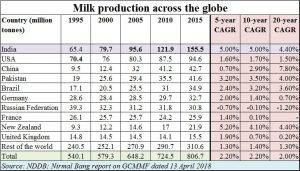

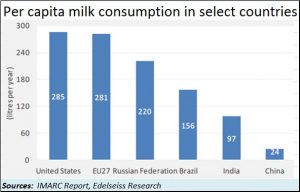

What is more interesting is that the market is likely to grow even further. A look at the per capita consumption numbers points to this (see chart). Expect this industry to be at least five times it current sixe within the next two decades.

What is more interesting is that the market is likely to grow even further. A look at the per capita consumption numbers points to this (see chart). Expect this industry to be at least five times it current sixe within the next two decades.

That is one more reason why Maharashtra, along with the central government, should treat milk production with immense care and strategy. It is essential not to undo all the good work that Kurien has done.

Exploitative Maharashtra

After achieving quite a degree of success in Gujarat, Kurien approached the cooperative leaders in Maharashtra and urged them to join his cooperative movement. All of them declined to take up his offer (all of them were from the Congress. The NCP had not been formed at that time). And the reason was simple.

After achieving quite a degree of success in Gujarat, Kurien approached the cooperative leaders in Maharashtra and urged them to join his cooperative movement. All of them declined to take up his offer (all of them were from the Congress. The NCP had not been formed at that time). And the reason was simple.

Kurien’s objective was to guarantee a a fair price to the farmers, and not to politicians. Maharashtra’s politicians saw the cooperative movement as a means of getting votes (by creating vote banks) and making money. This divergence in objectives explains to a great extent why milk producers are paid less in Maharashtra than in Gujarat.

It was to de-risk farmers that the present government headed by Devendra Fadnavis decided to start a new cooperative in Nagpur with the help of NDDB (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2017/05/maharashtra-derisks-farmers/). On 17 October, 2016, Maharashtra entered into an agreement with NDDB (National Dairy Development Board) which is mandated to promote milk cooperatives across India. Instead of paying Rs.16-22 per litre of milk that many cooperatives in Maharashtra were paying, the new cooperative in Nagpur began paying Rs.26.

Today, the Nagpur headquartered cooperative accounts for collection of around 1.9 lakh litres daily and pays the farmers a decent price of Rs.35.75 a litre for buffalo milk (though it offers only Rs.22 a litre for cow’s milk). The payment is made on the basis of fat content. Thus the only way the cow owners can get more money is by producing more milk, letting volumes compensate for the lower price. The other cooperatives continue paying around Rs.22 a litre (or less) for all types of milk.

Today, the Nagpur headquartered cooperative accounts for collection of around 1.9 lakh litres daily and pays the farmers a decent price of Rs.35.75 a litre for buffalo milk (though it offers only Rs.22 a litre for cow’s milk). The payment is made on the basis of fat content. Thus the only way the cow owners can get more money is by producing more milk, letting volumes compensate for the lower price. The other cooperatives continue paying around Rs.22 a litre (or less) for all types of milk.

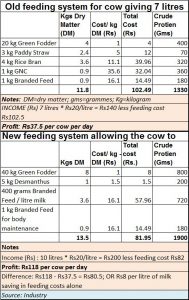

Increasing volumes should not be difficult. By just modifying cattle feed a bit, the cows can be made to generate at least 50% more milk, thus causing daily surpluses per litre to swell (see table). But farmers won’t produce more if the prices they get from other cooperatives remain low. Moreover the cow slaughter ban has turned off many farmers from cows. Expect buffaloes to be the mainstay for the diary industry in Maharashtra as well. But the unwillingness to produce more because of low prices offered by the private dairy sector is indeed the real truth behind the current milk crisis.

It was to mitigate the distress of the farmers that the Fadnavis government announced an MSP (minimum support price) for milk in Maharashtra. It decreed that cooperatives must pay Rs.26 a litre.

Of course, that would cause some of the profits of cooperatives to vanish; even though many cooperatives invariably find ways to show losses in the milk business. That isn’t surprising either. Because this would be akin to the losses that were posted by Maharashtra’s cooperative banks year after year, till till of course their boards were superseded and new teams were put in place place.

Maharashtra’s cooperatives do not want to pay the higher price, and want the state to pay the difference of Rs.6 as a subsidy. But why should the state do this? The demand is absurd!

More absurdities

What is even more absurd is the manner in which politicians across the spectrum have joined the fray to demand such a subsidy. What is even more surprising is the inability (or is it unwillingness) of the government to put the above facts in the public domain and popularize this through media and the government machinery. If the story is told well, people – including farmers — will realise the speciousness of the arguments that are being bandied around.

After all, isn’t Hatsun, India’s largest private sector dairy headquartered in Tamil Nadu paying the farmers Rs.26 a litre. So is Heritage, the company run by the family of Chandrababu Naidu, currently chief minister of Andhra Pradesh. Even multinational corporations like Nestle pay this minimum price – and often pay a little more – to their milk producers. This is also true in the case of players like Britannia and Hindustan Unilever.

So why should Maharashtra’s dairy farms not pay the farmers this amount? It just does not make sense.

Defrauding the taxpayer?

In the absence of cogent explanations, and in the face of absurdities explained above, one is left with only one question. Why are the farmers not demanding that Maharashtra’s private dairies also pay what dairies around India are paying? Obviously, what is sauce for the goose, must be sauce for the gander!

In the absence of cogent explanations, and in the face of absurdities explained above, one is left with only one question. Why are the farmers not demanding that Maharashtra’s private dairies also pay what dairies around India are paying? Obviously, what is sauce for the goose, must be sauce for the gander!

Could it be that there is a deliberate attempt to create an atmosphere where the state succumbs, and actually agrees to pay a subsidy?

Consider Maharshtra’s milk production. The state accounted for 10.153 million tonnes of milk during 2015-16. Even a Rs.3 subsidy per litre translates into Rs.3,045 crore. At Rs.6, the amount will be double. Could this be one more way of making the tax payer pay for elections through some sleight of hand transaction of the government? Why else is the government allowing an atmosphere to be created where it will be compelled to buckle down and grant the subsidy to the farmers?

Already, the states rankings — according to Niti Aayog — are terrible. Its debt is one of the largest in the country (see chart). And if it grants this subsidy, its debt will mount even further.

There are other signs of collusion. Watch how the enquiries into the mind-boggling irrigation scam have arrived at no conclusion or conviction. Note how some political leaders who were in custody were released, and the investigations do not appear to be moving ahead. Observe how the investigations into the Telgi scandal have not been talked about, even though his widow came to the government with documents to show that the proceeds from the stolen money were a great deal more than officially recorded? Also remember that any notion of enquiry into the large scale auction of police posts has been almost forgotten and may actually get buried, in spite of public denouncements by former police commissioner J. Ribeiro.

When it comes to graft money, almost all politicians, even bureaucrats, manage to scramble to the same side. The lure of lucre can be a great binding agent.

Is the milk agitation the outcome of such a lure?

COMMENTS