https://www.freepressjournal.in/analysis/two-measures-that-could-empower-marginal-farmers-land-lease-and-fpos

Land lease and FPOs could benefit marginal farmers

RN Bhaskar — 15 October, 2020

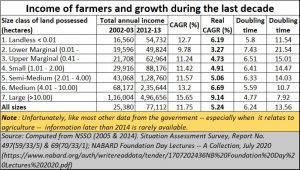

Time and again, new numbers pop up, reconfirming an old truth – that India’s farmers are in distress. Especially small farmers. A set of figures that is available in Nabard’s Foundation Day Lectures — A Collection brought out in July 2020, is quite interesting and  illuminating (https://www.nabard.org/auth/writereaddata/tender/1707202436NB%20Foundation%20Day%20Lectures%202020.pdf). Those numbers have been reproduced alongside.

illuminating (https://www.nabard.org/auth/writereaddata/tender/1707202436NB%20Foundation%20Day%20Lectures%202020.pdf). Those numbers have been reproduced alongside.

Watch the first row of numbers and look at the column titled Real CAGR. You will observe that landless farmers saw a faster growth in come than most marginal cultivators. You will also notice that landless farmers enjoyed a higher income than most landowner farmers.

At the same time do study the numbers for medium and large farmers. Their incomes are multiple times higher than the incomes of small farmers. And the real CAGR for such farmers are also much higher.

Both sets of numbers confirm two things

- That cultivation is not very remunerative for small and marginal farmers. Working on other people’s farms or elsewhere is more profitable.

- That it is always the small farmer who gets exploited. Medium and large farmers always find ways to make more money, cutting out middlemen, striking deals with industry or customers. It is even more profitable when the purchaser is the government – as in the case of rice and wheat. There collusive relationships and a corrupt FCI ensure that there is a lot of moolah to be picked up.

And this is where the three agriculture related legislations fall short. They are excellent pieces of legislations. They may work in the long run. But when a farmer community is distressed, he has no patience or need for the long run. He wants immediate solutions.

Two solutions

This author believes that there are two things that the government should do. First, allow for contract farming which also permits the leasing of land from farmers for periods of up to three years. Put in conditions that the farmer must earn from the land at least the average income a landless farmer earns and multiply this number into the acres of land taken on lease. Make a provision that the farmer will also earn some money if he works on his own land, though that should never be made compulsory. This protects farmers from losing ownership of their land. Yet they can continue working as farmers. And they can earn more (risk-free money) than they do now. Moreover, since the contractor now controls the land, the questions of farmers reneging on contracts at the time of harvest are no longer relevant. It will make contract farming more attractive, without causing any additional distress for farmers.

Second, focus less on giving money and subsidies directly to farmers (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2020/04/for-milk-subsidies-is-the-path-to-perdition/). Subsidies don’t go very far. In fact, they weaken farmers further, making them depend on subsidies more and more, and not sharpening their commercial instincts in farming practices. Instead use the money to bolster FPOs or farmer producer organisations. These are organisations that are supposed to function in much the same way as the milk cooperatives do. They are owned by farmers, just as envisaged by Verghese Kurien, the man who helped make India the largest milk producer in the world (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2019/08/indian-bureaucrats-almost-shortsold-the-milk-industry-at-fta-cpec-negotiations/).

Kurien insisted that the farmer gets a higher share of the market price of any agricultural produce than either processors or marketing/distribution players. To ensure that marketing distribution and processing did not eat away into the income that farmers could earn, he set up cooperatives and federations of cooperatives so that procurement, processing, marketing, and distribution was taken up by them. As a result, cooperatives that are run along the lines or principles laid down by Kurien today ensure that the farmer gets at least 60% of the market price for milk. In Gujarat and Tamil Nadu the farmer gets a higher share – of over 70%. Interestingly, the biggest supporter of milk producers in South India is Hatsun, a privately managed listed company, that gives farmers Rs.26 a litre. Compared to either the Gujarat cooperatives or Hatsun, Maharashtra’s cooperatives grumble about giving even Rs.25. Both Maharashtra and neighbouring Karnataka also want their respective state governments to milk producers a milk subsidy. This is despite Gujarat’s cooperatives and Hatson successfully managing the milk business without any subsidy.

Politicians in these states seldom ask the critical question: If Gujarat and Tamil Nadu can give farmers Rs.26 a litre without begging for subsidies, surely the systems in Maharashtra and Karnataka must be terribly inefficient. Subsidies will further promote inefficiency. That will make them slide down a continuing spiral. That, in turn, will drag down the efficient players as well. It is a surefire way of harming, not helping, small farmers.

FPOs

To be fair, it must be mentioned that the government, along with NDDB and Nabard, has been trying to promote FPOs to do precisely what Kurien wanted to do with milk. The intent is right, but the structures are not yet in place.

Since vegetables and fruit are not standardized, and not always available round the year, lots of flexibilities must be built in. Could the FPOs not negotiate on behalf of small and marginal farmers and get them a better price? Could they not become aggregators of small amounts of produce from each farmer and pass it on to a super aggregator? More importantly, should not processing and marketing facilities be developed by the super aggregator FPOs so that small farms get a better price even when there is surplus stock in the markets. This way a depression of prices can be mitigated.

Since vegetables and fruit are not standardized, and not always available round the year, lots of flexibilities must be built in. Could the FPOs not negotiate on behalf of small and marginal farmers and get them a better price? Could they not become aggregators of small amounts of produce from each farmer and pass it on to a super aggregator? More importantly, should not processing and marketing facilities be developed by the super aggregator FPOs so that small farms get a better price even when there is surplus stock in the markets. This way a depression of prices can be mitigated.

Unfortunately, while FPOs are being set up, and the numbers have been increasing, most are without a governance structure. The concept of promoting a federation of FPOs hasn’t even been embarked upon till now. That federation could play the role of the super FPO. That is what the government has not done. Not in legislation, and not even in narrative or practice.

Thus, a cluster of FPOs cannot coalesce and become a Federation, also take up procurement, marketing, and distribution functions just at GCMMF (Amul) does for the milk cooperatives.

The focus on numbers is obvious. In July 2020, the government issued Guidelines for the formation of FPOs (http://agricoop.nic.in/sites/default/files/English%20FPO%20Scheme%20Guidelines%20FINAL_0.pdf). It made clear its resolve in having around 10,000 FPOs in the country.

However, the data about how many FPOs exist in the country, and the volume of business done by them have not been made available for study and analysis. That would have allowed farmers to see how the FPOs have fared.

Moreover, reports from the ground suggest that most of these FPOs are in the nascent stage of their operations with shareholder membership ranging from 100 to over 1,000 farmers. Many exist only on paper. These FPOs require not only technical handholding support but also adequate capital and infrastructure facilities including market linkages for sustaining their business operations.

Yet the preoccupation with numbers rather than governance related structures is baffling. The focus on numbers is evident from a PIB statement (https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1605030) – “. . . pursuant to the budget announcement, the Government in the Department of Agriculture Cooperation and Farmers Welfare (DAC&FW) has approved a new Central Sector Scheme titled “Formation and Promotion of Farmer Produce Organizations (FPOs)” to form and promote 10,000 new FPOs with a total budgetary provision of Rs 4,496 crore for five years (2019-20 to 2023-24) with a further committed liability of Rs 2,369 crore for the period from 2024-25 to 2027-28 towards handholding of each FPO for five years from its aggregation and formation. . . . NABARD has reported that currently there are around 6,000 Farmer Producer Organisations (FPOs) existing in the country, which have been promoted by the Government, NABARD, State Government departments and Civil Society Organizations. Out of these FPOs, NABARD has promoted 4,317 FPOs, which include 2,154 FPOs supported out of Producers Organization Development and Upliftment Corpus (PRODUCE) Fund. During 2014-15, the Government had created PRODUCE Fund with a corpus of Rs 200 crore in NABARD for the promotion of 2,000 FPOs in the country. Against the target of 2,000 FPOs, NABARD has sanctioned 2,154 FPOs as on 31.10.2019.”

The only place some additional details of FPO structures can be found is on the website of the Small Farmers’ Agribusiness Consortium or SFAC (http://sfacindia.com/Procurement.aspx). It was nominated as a Central Procurement Agency for pulses and oilseeds in November 2012.

As the website puts it, “The logic of this model is that farmers themselves are the most appropriate agents for conducting procurement operations and their collective institutions (such as FPCs) are the most efficient and cost effective procurement agencies available.”

But it appears that it has not reached critical mass yet. Consider how “during kharif 2013-14 and rabi-2014, SFAC procured 71,880 MT of pulses and oilseeds amounting to Rs.244.03 Crore at Minimum Support Price (MSP) under Price Support Scheme (PSS) of Government of India from 6 States namely Andhra Pradesh, Gujarat, Karnataka, Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh & Rajasthan .The total number of farmers benefitted from this initiative was 29,095 and 56 FPCs were engaged in the MSP operation.”

The numbers look impressive. But it is worth noting that the five year-average of pulse production in India is 20.26 million tonnes. And the five-year average production for oilseeds stands at around 30 million tonnes. SFAC has not been able to procure even a million tonnes. This is in spite of having a central government mandate and having around 14% of the total number of FPOs in the country (see table).

Most farmer organisations are convinced that FPOs could be a big solution to the agricultural crisis India is in. That coupled with contract farming (including lease of landholdings) could significantly alleviate the plight of small and marginal farmers who account for 82% of the total farmer population (https://www.agroworldindia.com/fpo.php). Interestingly, countries like China, Vietnam, and Indonesia etc. have also adopted the FPO approach.

On March 3, 2020, in a reply to a query in the Rajya Sabha, Anurag Singh Thakur, Union Minister of State for Finance & Corporate Affairs, stated that in order to promote the 10,000 FPOs, the government had a “total budgetary provision of Rs 4,496 crore for five years (2019-20 to 2023-24) with a further committed liability of Rs 2,369 crore for the period from 2024-25 to 2027-28 towards handholding of each FPO for five years from its aggregation and formation.”

The fund allocation for FPOs is pathetically small. The government appears to be more interested in giving doles to individual farmers than strengthening the farm procurement, processing, and marketing infrastructure. Moreover, the focus on number of FPOs and not the quality of functioning could undermine this entire exercise. Eventually, the government could be pouring good money over bad. Worse, if the FPOs won’t work the way they were meant to, they run the risk of become another tool which rapacious middlemen will use to both fleece the exchequer and exploit small farmers.

Could it be that the government is not yet ready to remove the middleman? How else do you justify the way Uttar Pradesh functions? It has a BJP government. SFAC has around 55 FPOs in that state. Yet the most rudimentary of farmer cooperatives – for milk – has not taken off in that state.

This is despite a working model for milk cooperatives being around for over six decades. An impressive working structure exists. Organisations like the NDDB are there to monitor the proper governance of milk cooperatives.

Unlike states like Gujarat and Tamil Nadu, which pay Rs.26 and more per litre of milk to farmers, UP pays around Rs.15-16 per litre to farmers. Not surprisingly, farmers are most distress in the largest milk producing state in India (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2020/09/india-plundered-again-by-tweaking-rules-against-prosperous-states-and-encouraging-profloigacy-irresponsibility/).

This is where the three new legislations relating to agriculture will fall woefully short of the government’s claimed objectives. Unless modifications are made to contract farming, thus allowing for lease of land, and unless a structure is mandated for the working of FPOs, the small and marginal farmer will not benefit much, certainly not in the short run.

As for the long-term, as the saying goes, in the long run, all of us are dead.

COMMENTS