MARKET PERSPECTIVE by Jawahir Mulraj

MARKET PERSPECTIVE by Jawahir Mulraj

India must get its act together, mere intentions aren’t enough

By J Mulraj — Nov 15,-21 2020

If India wants to achieve its potential to be an economic powerhouse, it must get its act together and address its weaknesses. India has been taking sensible economic and policy decisions, but in some cases, policy makers seem to be satisfied with mouthing good intentions, but not adequately following up on them.

For example, India recently opted out of RCEP (Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership), a free trade agreement recently signed by 15 countries with a combined 30% share of global trade, making it the biggest trade block in history. India’s concerns were mainly on two things. One, India is predominantly yet an agricultural economy, with over 50% of its population dependent on it for survival, and allowing imports at low rates from the block would harm farmer interests. Two, given the political issues emanating from the border stand off with China, becoming a member of RCEP would have adverse implications.

For example, India recently opted out of RCEP (Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership), a free trade agreement recently signed by 15 countries with a combined 30% share of global trade, making it the biggest trade block in history. India’s concerns were mainly on two things. One, India is predominantly yet an agricultural economy, with over 50% of its population dependent on it for survival, and allowing imports at low rates from the block would harm farmer interests. Two, given the political issues emanating from the border stand off with China, becoming a member of RCEP would have adverse implications.

Although more than half the population is dependent on agriculture, the sector earns only around 14% of national income, a hugely adverse terms of trade. Several Governments in the past have pointed to the inequity of this, but progress to correct the situation is slow. Opposition, largely on political lines, to the introduction of two farm bills, has delayed reforms. A chunk of the value added in agriculture (i.e. what the urban consumer pays minus what the farmer gets for the produce) goes to the middlemen who control the ‘mandis’, or designated markets at which the farmer must sell the produce. The bills sought to give farmers freedom to sell outside the mandis, if he wished.

Better roads would also help improve farm income as some 30% of fruits and vegetables are destroyed in transit, due to poor rural roads. Construction of better roads connecting villages to urban areas is hampered due to high land acquisition costs.

Good intentions, but, for several reasons, slow action.

Or take capital raising. As these columns have pointed out, the total assets of financial institutions are $ 379 trillion, globally. These institutions are looking for alternative ways to invest this, given the low interest rates prevalent in developed countries.

India’s Finance Minister, Nirmala Sitharaman and, before her, Arun Jaitley, have, in budget speeches, professed their intentions to spend $ 1.5 trillion on infrastructure alone, over the next 5 years. Good infrastructure is necessary to attract more FDI, to help domestic manufacture (taking up its share in GDP and also provide jobs) and for reducing logistic cost and improve export competitiveness.

So we mouth our good intentions to spend $ 1.5 trillion over 5 years, and then feel that, having done that, we don’t need to act. But we do! In 2019 total fund raising in India, via IPOs, offer for sale, and qualified institutional placements, was Rs 81,174 crores (US $ 12 b @ Rs 70/USD, then), hence in 5 years domestic savers would provide $ 60 b. Where will the rest come from? There is no effort to tap global markets, hence the $ 1.5 trillion would be a mere mouthing of intentions without a plan.

Not so China.

China has, last week, raised $ 4.7 b. in negative yield bonds! Why can’t India, desperate for funds for infrastructure, do that?

China’s Ant Corporation also successfully made (but later cancelled after the Shanghai stock exchange refused to list it for strange reasons) the largest ever equity IPO of $ 37 b. (larger than that of Saudi Aramco) and which got bids for $ 3 trillion!! w

The Chinese Government recently raised $ 6 b. by selling bonds directly to retail investors in USA! This, despite the trade war and tension in the region between USA and China. President Trump signed an executive order last week, banning US Financial Institutions from investing in Chinese weapons manufacturing companies.

So India can, if it gets its act together, raise international resources from a global financial sector that is starved for better yields and hungry for returns.

But for that we must act and not merely mouth intentions.

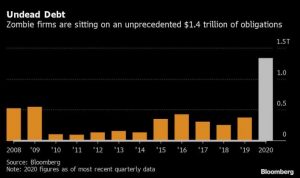

In a recent analysis by Bloomberg, it was discovered that nearly 20% of US companies (including the likes of Boeing, Delta Airlines, Macys etc were zombie firms which had accumulated high debt, to survive the pandemic, but would be unable to repay it. Total debt of these zombies is $ 1.4 trillion (compare this to $ 500 b at the height of the 2008 global financial crisis).

In a recent analysis by Bloomberg, it was discovered that nearly 20% of US companies (including the likes of Boeing, Delta Airlines, Macys etc were zombie firms which had accumulated high debt, to survive the pandemic, but would be unable to repay it. Total debt of these zombies is $ 1.4 trillion (compare this to $ 500 b at the height of the 2008 global financial crisis).

So there is a large pool of global money and India must get its act together to get a slice of it.

Then, of course, there is the painstakingly slow judicial system, and a relaxed investigative and supervisory system, which we mouth our intentions to correct, but do little about. Moneylife had written about the ability of the Sahara group to raise over Rs 1 lac crores, even as he was incarcerated! How come this was possible and what were the supervisors doing about it?

Belatedly, SEBI is asking Sahara to deposit Rs 62,600 crores ($ 8.4 b.) upon threat of cancellation of parole.

Similarly, several banks, mainly Public Sector ones, have, either due to poor appraisal, or due to instructed lending, piled up bad loans and have recovered very little of these loans. Out of the Rs 17,800 crores lent to 66 large defaulters, IOB has recovered a mere 0.5%.

SEBI has asked the NSE to increase its Investor Protection Fund (IPF) from Rs 600 crores to Rs 1500 crores. That’s good.

But then, what had SEBI done, when the IPF of failed commodity exchange NSEL, mysteriously vanished overnight and nothing of the fund was used to compensate its investors? NOTHING! It washed its hands off the case, stating that it was not the regulator for a commodity exchange. (both were later merged, but that’s of no comfort to the victims).

The sensex ended the week flat, at 43,832. With bank deposits considered a bad option, given their low deposit rates, negative to inflation, and given their track record of bad loans and abysmal recovery rates, household savings are going towards equity.

Inflows into the equity market can be bolstered if India gets a higher share of global funds. US President Trump is strongly asking its financial institutions to disengage from China, even though the industry continues to fund it. If India gets its act together, it can attract more FDI and FII money.

That, though, needs actions. After all, they speak louder than words.

COMMENTS