NBFCs become more relevant to India. Is that a risk?

RN Bhaskar

All of a sudden, there’s renewed interest in what non-banking finance companies (NBFCs) are doing in India. Some are alarmed. Some canny observers are happy. Yet, the whims of the regulator, namely the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) cannot be ignored. For years, the RBI frowned on the role NBFCs played. It took years to get an NBFC licence. And even today, the rules are crafted in such a way as to make NBFCs hobble along, and not compete with mainstream banking.

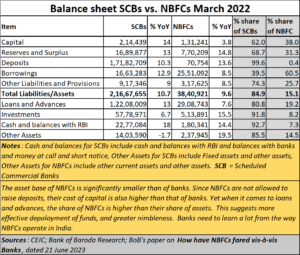

Most annoyingly, NBFCs are generally not allowed to invite deposits. They have to borrow from banks, or mutual funds, or even insurance companies. They have to use their own funds, or in some cases even resort to commercial paper issuances with prior RBI approval.

Thus, their cost of borrowing is significantly higher than that of banks. There are restrictions on how much to lend to different sectors, and the RBI has further classified them into four boxes. The RBI has introduced a Scale Based Regulation (SBR) for NBFCs. Accordingly, you have the Base Layer (NBFC-BL), Middle Layer (NBFC-ML), Upper Layer (NBFC-UL) and Top Layer (NBFC-TL) based on their size, activity, and perceived riskiness. Sixteen entities have been identified for categorisation as NBFC-UL under the framework (source: CARE Edge Ratings paper titled ‘NBFCs: Retail Lending Thrives; Asset Quality Continues to Improve’ of 3 July 2023).

IMF frowns at shadow banking

Globally, such NBFCs are clubbed along with other entities under the banner of ‘shadow banking’ According to an IMF report on this subject (https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/fandd/issues/Series/Back-to-Basics/Shadow-Banks), such an entity “looks like a bank and acts like a bank? Often it is not a bank—it is a shadow bank.”

The IMF report goes on to add, “”Using the entity-based measure, the latest report (end-2015 data) shows that the euro area shadow banking system is now the largest globally, comprising 33 percent of the total (up from 32 percent in 2011), whereas the US shadow banking system has declined from 33 percent to 28 percent. Across the jurisdictions contributing to the FSB exercise, the global shadow system peaked at $62 trillion in 2007, declined to $59 trillion during the crisis, and rebounded to $92 trillion by the end of 2015. The “functional” categorization (a narrower categorization of 27 jurisdictions) shows that of the total $34.2 trillion, the largest part of shadow banking is made up of asset-management-type activities—some 22 percent of the total.”

The IMF report goes on to add, “”Using the entity-based measure, the latest report (end-2015 data) shows that the euro area shadow banking system is now the largest globally, comprising 33 percent of the total (up from 32 percent in 2011), whereas the US shadow banking system has declined from 33 percent to 28 percent. Across the jurisdictions contributing to the FSB exercise, the global shadow system peaked at $62 trillion in 2007, declined to $59 trillion during the crisis, and rebounded to $92 trillion by the end of 2015. The “functional” categorization (a narrower categorization of 27 jurisdictions) shows that of the total $34.2 trillion, the largest part of shadow banking is made up of asset-management-type activities—some 22 percent of the total.”

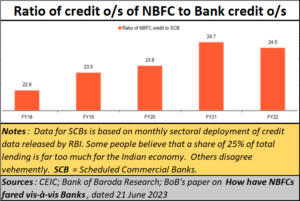

In India, NBFCs account for almost 25% of credit outstanding (the rest catered to by banking or quasi banking entities. entities). So, should they be viewed as a threat?

Not really, despite all that the IMF report says. For instance, the IMF report says “Shadow banking, in fact, symbolizes one of the many failings of the financial system leading up to the global financial crisis. The term “shadow bank” was coined by economist Paul McCulley in a 2007 speech at the annual financial symposium hosted by the Kansas City Federal Reserve Bank in Jackson Hole, Wyoming. In McCulley’s talk, shadow banking had a distinctly US focus and referred mainly to nonbank financial institutions that engaged in what economists call maturity transformation . . . But because they are not subject to traditional bank regulation, they cannot—as banks can—borrow in an emergency from the Federal Reserve (the US central bank) and do not have traditional depositors whose funds are covered by insurance; they are in the ‘shadows’.”

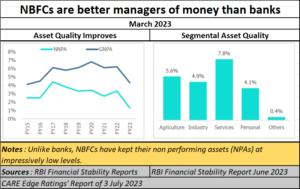

But when it comes to India, NBFCs are to be admired. They have turned out to be better managers of money, despite their high cost of funds. Their level of non-performance assets (NPAs) would make any responsible banker blanch. Ditto with their asset quality.

As a senior banker in India points out, “NBFCs play a diff role in our eco system compared to US and China. Banks have failed to penetrate after years. Only 5% Indians have credit cards where do the rest go ? That’s the space NBFCs ]occupy. They have taken deep geography products and specialization and [offer a] great service – gold loans, consumer durables, micro finance. Nothing would have happened without NBFCs and even today they co exist. Banks lend to NBFC wholesale and NBFCs then take this and deliver it to retail and SME (small & medium enterprises) customers in products and segments and to customers that banks do not reach”

Adds a Bank of Baroda report — 21 June 2023) on ‘How have NBFCs fared vis-à-vis Banks’: “NBFCs have also carved niches in specific areas on the lending side such as auto, gold, and transport operators as against banks which have a more broad-based lending portfolio. The proportion of their lending is around 25% of that of banks and has been stable in the range. Hence, their contribution to the financial landscape will remain important in the coming years.”

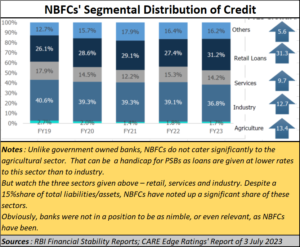

This can be clearly seen from the manner in which NBFCs operate. While government owned public sector banks (PSBs) are hobbled by agricultural loans, which offer them very poor (government mandated) interest rates, NBFCs stay clear of agricultural loans in general, but focus on meeting personal loans needed by people from the agricultural sector. If the government really wants to become meaningful to its rural population, it should allow NBFCs access to low cost funds from NANARD and similar banks, so that the rates of interest for small rural borrowers goes down further. That would allow NBFCs to play a better role than they currently do. They have shown that they can penetrate deeper into villages than any bank can.

This can be clearly seen from the manner in which NBFCs operate. While government owned public sector banks (PSBs) are hobbled by agricultural loans, which offer them very poor (government mandated) interest rates, NBFCs stay clear of agricultural loans in general, but focus on meeting personal loans needed by people from the agricultural sector. If the government really wants to become meaningful to its rural population, it should allow NBFCs access to low cost funds from NANARD and similar banks, so that the rates of interest for small rural borrowers goes down further. That would allow NBFCs to play a better role than they currently do. They have shown that they can penetrate deeper into villages than any bank can.

But when it comes to catering to the needs of industry, services or retail loans, watch the NBFCs compete with banks head-on and still do a better job. Their ability to compete with banks (which have access to low-cost funds and deposits) is much in evidence. That NBFCs do this without allowing their advances to become NPAs is highly commendable.

“Over the last five years, loans to industry lost market share from 40.6% in FY19 to 36.8% in FY23 and yet continued to constitute the largest segment, followed by personal loans at 31.2%, services at 14.2% and agriculture at 1.7%. Advances to the retail segment grew the fastest in H1FY23. Government-owned NBFCs have been ceding ground in the industry segment. According to RBI’s Financial Stability Report June 2023, the NBFC-UL group recorded higher credit growth (y-o-y) of 18.8% and a better GNPA ratio of 3.7% as of March 2023 than the overall NBFC sector,” says a CARE Edge Ratings report.

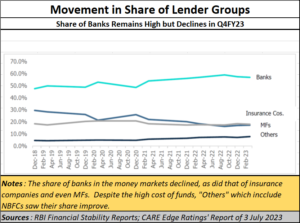

The report adds that NBFCs have traditionally been the largest net borrowers of funds from the financial system. NBFCs owed close to 57% in FY23 (similar levels in FY22) to banks followed by 17.3% (18.4% in FY22) to MFs (mutual funds) and 18% (17.6% in FY22) to insurance companies. That effectively makes NBFCs both saviours of, as well as competition to, the mainstream banking system. That could explain the heartburn that NBFCs cause.

Obviously, banks were not in a position to be as nimble, or even relevant, as NBFCs have been. It is therefore not surprising that the market share of banks has not grown much – even after licences were given to new players to set up banks. The shares of Insurance and MFs have declined even more sharply. And except for a slight dip last year, NBFCs continue to grow, not because they are favoured, but because they are both nimble and relevant.

That is why, if the government wants more rural folk and SMEs to come into the banking system – it has been focusing on Aadhaar and its manifold schemes – it should be empowering more NBFCs to reach out to small consumers with small needs. Banks are stodgy. They can be lenders of big money. But NBFCs have shown that nothing is too small for them. Their ability to profitably penetrate even the remotest of markets is truly incredible.

One hopes that the RBI and the government are listening.

COMMENTS