The dairy sector could be in for more confusions and value destruction

By RN Bhaskar

Image generated through https://deepai.org

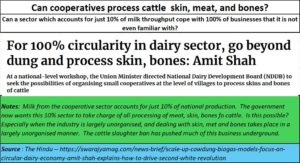

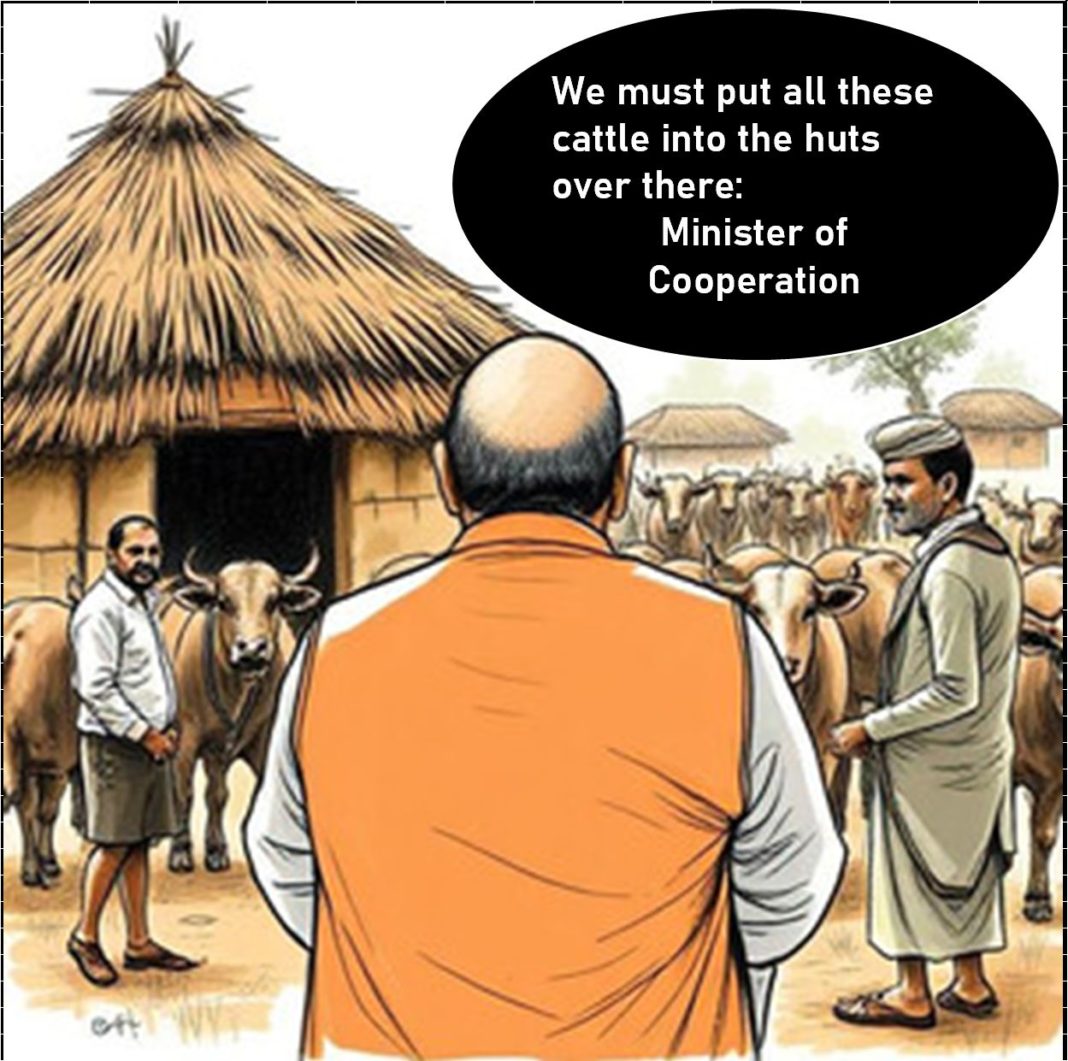

On 3 March 2025, the government’s Press Information Bureau or PIB came up with a very interesting item (https://pib.gov.in/PressReleseDetailm.aspx?PRID=2107807®=3&lang=1). It was titled ‘Union Home Minister and Minister of Cooperation Shri Amit Shah inaugurates the “Workshop on Sustainability and Circularity in Dairy Sector” in New Delhi’.

The contents of the news item were also such that they made many informed observers raise their eyebrows in incredulity.

Consider for instance what The Hindu reported. Shah wants the dairy sector to go beyond cow dung, and even take up processing cattle skin, (by implication) meat, and bones. Anyone who knows even a bit about the dairy cooperative business in India would scoff at such advice.

Consider for instance what The Hindu reported. Shah wants the dairy sector to go beyond cow dung, and even take up processing cattle skin, (by implication) meat, and bones. Anyone who knows even a bit about the dairy cooperative business in India would scoff at such advice.

After all, how can a sector which accounts for just 10% of the milk procurement, deal with 100% of bones, skin and meat. Is it even feasible? Can leather processing really be decentralised? It just cannot be done, because of the very nature of this sector. It is not organised.

Great idea, but . . . . .

The Amit Shah address appeared to be focussed on “setting up the entire chain from farm to factory in the village itself”. Great idea. But his advisors should have told him about some of the practices of the past. Probably, then, he might have sung a different song.

For instance, even collecting dung has proved to be difficult. Narendra Modi tried it through hi “gobar banks” when he was chief minister of Gujarat (https://asiaconverge.com/2013/03/the-cow-jumps-over-the-moon/). Despite a great deal of promotion, it was given up. It was tried through NDDB as well — https://asiaconverge.com/2018/04/shit-can-mean-big-money/. Even though numbers pointed one way, local practices and logistics pointed the other way.

For instance, most villages make patties (small flat cakes) out of dung to plaster their walls. Dung is a great insulator against extreme weather. Some use the patties as fuel. They use dung paste to decorate the front porch of their houses. Marginal farmers thus have little dung to give to anyone, let alone get a price for it.

Dairies are fragmented

As mentioned above, cooperatives account for just 10% of milk collection in the country. Almost 30% of the milk produced appears to be used for self-consumption by cattle owning families.

These statements were made during the keynote speech at the CII organised Dairy Vision 2025 held in Delhi (https://www.nddb.coop/about/speech/dairyvision). The people present at this event where the 10% share was mentioned included government representatives like Radha Mohan Singh, minister of agriculture, Anup Thakur, Secretary, Department of Animal Husbandry, Dairying and Fisheries, MK Jalan, Chairman, CII National Committee on Dairy, and Shri Chandrajit Banerjee, Director General, CII. So, why did they not advise Shah about this?

In the speech it was mentioned that “Milk cooperatives procure about 10% of the total production which is about 18% of the marketable surplus. A similar quantity is reportedly procured by the private sector. Both the sectors together account for only about 35% of the marketable surplus. This means that a large quantity of milk remains unprocessed. The installed processing capacity of the cooperative sector is 43.3 million litres /day while they actually process an average 33.5 million litres/day. As per available data, the registered (as different from installed) capacity of private sector milk processors in India is 73.3 million litres/day. It is recognized that post liberalization in 1991, the role of private sector in dairying has increased significantly thereby accounting for a significant share of the market.”

Effectively, much of the milk is produced by the unorganised, and unregistered, sectors. And what is described as “unprocessed” milk is actually milk held by very small units, even householders. That milk goes into making curd, shrikhand, cheese, and is even sold at pasteurised milk to people who want small quantities of milk urgently.

Almost 80% of the ownership of cattle is by very small farmers. Even landless labourers often opt to rear a cow or a buffalo. They tie it to any tree near their place of dwelling, and take it out to graze every day. Much of the milk is usually consumed by the family, and some of it gets sold. Neither the production, nor the sale of such milk, is registered, at least for large sections of this population.

When the cattle grows old, the owner sells it to a broker who then transports it to a region where it can be slaughtered. After the meat is sold, the remains get processed – provided they can be spared the wanton abuse by gau–rakshaks (vigilantes, who claim to be protectors of cattle). These gau-rakshaks spread mayhem and terror among small farmers.

The existence of these vigilantes has caused this entire chain of activity to go underground. For small cattle holders, the ownership of cattle is crucial — both for the nutritional needs of the family, and for the additional income from the sale of surplus milk.

Trying to fiddle with this type of ownership of cattle will only spell further havoc both for nutrition and supplemental incomes for the rural masses. The sale of cattle is inevitable, because the cattle owner must recover the cost of purchase of the (now old) cattle and create some funds for acquiring a new cattle head. Moreover, retaining ownership of old cattle is both inconvenient and expensive. Medicines cost money, and diseased aged cattle spread infections to the healthier ones.

So, while the entire process of skin, meat and bones is reasonably organised in the Southern states of India, it is unorganised in the rest of India especially where the cattle slaughter ban is in force. That is why, you will see the production of milk rising faster in India’s southern states than in northern states.

The tragedy of northern states

The tragedy of northern states

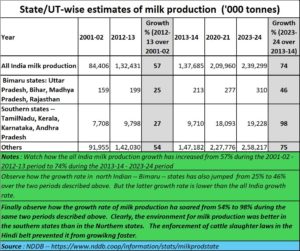

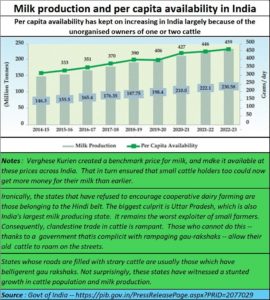

Has the cow slaughter ban helped the Hindi belt? No. The numbers sourced from NDDB point to how states in South India have benefitted immensely by a healthier growth of the dairy sector than those in the Northern region. Milk production soared by 98% during the 2023-24 — 2013-14 period in Southern states, compared to just 46% in northern states.

Clearly the states in the Hindi belt, which the central government has nurtured (https://asiaconverge.com/2021/08/poverty-in-uttar-pradesh-and-bihar-is-not-accidental/ ) have contributed to this problem. Uttar Pradesh, which is the largest producer of milk, has almost no cooperative movement to speak of. Policy makers fear the clout of middlemen who exploit the farmers. The government looks the other way even when farmers get exploited with lower-than-market-payments for the milk supplied to them. Sustainable dairy development must begin there.

The other problem is cattle slaughter laws.

Just look at the numbers. Prior to 2013, both the northern and southern states had a similar rate of growth. Now watch how northern states have a growth rate that is lower than the national average, and much lower than those of states in the south.

A more rapid growth rate in the south points to a more robust industry. It also points to better nutrition because more children from the poorer (often rural) sector can get a share of the milk produced. Players like R.G.Chandramogan, founder managing director of Hatsun Agro Products have shown that the private sector can be better than many politician-run cooperatives.

Like Dr. Verghese Kurien (https://asiaconverge.com/2013/05/strategic-vision-kurien-style/) who ushered in India’s milk revolution, Hatsun too focuses on farmer welfare, and makes him wealthier by reducing his cost of producing and selling milk. Today, Hatsun is the largest private sector milk company in India (2024 turnover Rs.8,000 crore), Like the late Dr. Kurien, he has demonstrated that a milk enterprise can be profitable without any subsidies or doles from the government, provided it is well managed and committed to farmer welfare.

But such an enterprise can succeed only in India’s southern states. That is where farmers can still sell the ageing cattle they had initially purchased. They do not face the risk of screaming vigilantes destroying the value of their cattle ownership. Not surprisingly, these are states where the leather and beef industries continue to thrive.

As for Northern states, the future is bleak.

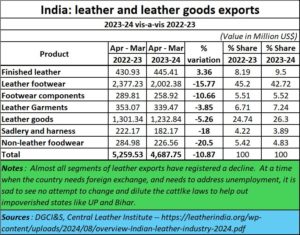

Thanks to the cattle slaughter ban, the growth of both leather and beef sectors has remained muted. This is unfortunate because leather continues to be a labour-intensive sector, and a huge foreign exchange earner.

Thanks to the cattle slaughter ban, the growth of both leather and beef sectors has remained muted. This is unfortunate because leather continues to be a labour-intensive sector, and a huge foreign exchange earner.

Can smuggling be called exports?

Northeast India is a mixed bag. The people there eat beef and pork, but increased saffronisation has pushed this trade underground. That makes the process of making these milk-deficient states self-sufficient that much more difficult.

That is why cattle smuggling from India to neighbouring countries is quite popular. If India’s policymakers put economics before ideology, this continued smuggling activity could be converted into a huge export opportunity. Instead of calling it smuggling, it could be promoted as exports.

Such a move could make the northeastern states get more milk, and more money. It could even become a booming export activity.

But when policymakers are guided by ideology, not economic sense, there are invariably at least two casualties – the country and poor people. The government’s policies on cattle are hurting small farmers. They are hurting labour-intensive industries like leather. And they hurt the country. India’s exports get hurt. Its nutritional standards get hurt. Also hurt are common folk who must cope with stray cattle on the roads. The best indicator of an administration with poor economic sense is the sight of roads filled with stray cattle.

That is why Shah’s statements are not grounded. They fail to address the crisis in rural India in general and the dairy sector in particular. India deserves a lot more. The pathetic performance of the dairy and allied sectors in recent times suggests that things could get a lot worse before they can even hope to get better.

===================

My latest podcast on Trump’s Tariffs. Do watch it and ask your friends to subscribe to this channel.

=========================

COMMENTS