Are there limits to a fudge?

RN Bhaskar

Both pictures are courtesy Canva — https://www.canva.com – The term 2+2=5 is reminiscent of George Orwell’s 1984 where the protagonist wonders if the constant propagation of this foolish formula could lead people to believing in it. Would it even matter then?

The last couple of months have been witness to a spate of reports pointing to errors or distortion of government data. Some called it a fudge. Others were a bit more charitable and called it a mistake in calculations.

Either way, the government was caught off guard. Normally, the government is quick to retort with barbs and whataboutery. This time, there was near silence. But charges of a fudge were up in the air.

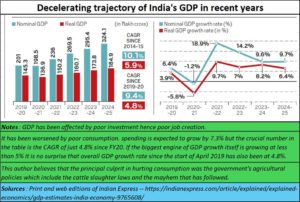

One of the first reports about this was on the GDP front. The warning had already been fired in July 2024 by none other than John Felman and his co-author Arvind Subramanian (https://www.business-standard.com/economy/news/union-budget-2024-25-three-macro-puzzles-and-policy-implications-124071901345_1.html).

As the article explains, “Josh Felman is Principal JH Consulting; Arvind Subramanian is Senior fellow, Peterson Institute for International Economics. But more relevant is the fact that Subramanian was the former chief economic advisor to the government of India and was quite familiar with the way numbers work. In the article, the authors wrote: “if both household consumption and saving are both weak, then household incomes must be very weak. But this is difficult to reconcile with strong GDP growth, because that normally leads to high incomes and employment. It’s much more logical to conclude that that weak consumption is a symptom of weak growth (and not its underlying cause).”

Put plainly, they were saying that the government’s numbers were not credible.

Government trumpeters however kept blaring through every channel that was available to them that the economy was in fine fettle. Then came the first blow at the end of the first quarter of FY25. GDP growth had crashed. It was nowhere near the figures that had been dished out earlier.

Even then government spokespersons kept up a straight face and said that the GDP growth rates would rebound in the following quarter.

If there were people who tried to believe in the government spiel, they were soon disappointed. By last fortnight, it became evident that the GDP growth rates hadn’t picked up even in the second quarter.

It was obvious that GDP growth had decelerated because of a variety of factors. One was the worsening investment climate. Government protectionism, had made prices go up, thus crunching demand. Rural incomes had been falling, ever since the government announced its ill-advised cattle slaughter laws. That in turn reduced the capital that small and marginal farmers had (https://asiaconverge.com/2023/01/sodhis-resignation-has-dire-warnings-for-agriculture-and-milk/). This was compounded by a fraying social fabric as screaming gau-rakshaks went about halting meat wagons. Forensics that are not available even for human beings were forced to look at animal meat instead. Economies don’t thrive when the social fabric starts to tatter.

Demonetisation took its toll on both small and medium enterprises as well as the rural sector which work with cash (Free subscription — https://bhaskarr.substack.com/p/demonetisation-is-someone-flying).

Demonetisation took its toll on both small and medium enterprises as well as the rural sector which work with cash (Free subscription — https://bhaskarr.substack.com/p/demonetisation-is-someone-flying).

The government claimed it would be good for the economy. Really? Another fudge?

The onset of Covid was a good excuse, but not good enough. The economy needed healing – on the rural side with better and humane policies being reintroduced (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ma2JBGQahzw). Investment climate needed to be nurtured back to health. Raids on business and imprisonment terms without trial frightened many entrepreneurs away from India. Money began flying overseas (Free subscription — https://bhaskarr.substack.com/p/money-is-flying-out-of-india).

When the present is tough, the best thing is to paint a rosy future – but one that is so far away that even if those visions don’t turn true, the spokesperson will have gone, and so will public memory.

GDP goalposts began changing rapidly.

Not surprisingly, instead of making forecasts for 2027, the government began giving out longer term forecasts. The new forecast is $30 trillion by 2030.

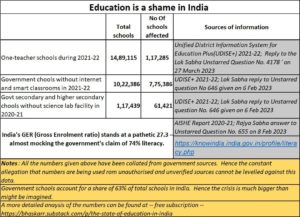

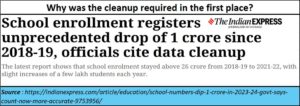

Equally worrisome was the disclosure just a couple of weeks ago, that school enrolments had fallen by 1 crore (https://indianexpress.com/article/education/school-numbers-dip-1-crore-in-2023-24-govt-says-count-now-more-accurate-9753956/). Policy makers tried to allay fears of ineptness at handling the school front by saying that the government had a better fix on numbers now.

The justification was bizarre. Did that mean that the government had been pushing out data without carefully vetting the numbers presented before the country?

In any case, the story of school education in India is terrible to narrate (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m74BaqgWD-g&t=145s). The figures tell it all.

In any case, the story of school education in India is terrible to narrate (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m74BaqgWD-g&t=145s). The figures tell it all.

Meanwhile, there were other reports that even the government’s claims on poverty reduction had been fabricated courtesy Niti Aayog, the government’s think tank. Two reports in The Wire (https://thewire.in/economy/new-study-takes-on-niti-aayogs-poverty-ratio-fall-claim and https://thewire.in/government/the-governments-claims-of-poverty-reduction-are-false-heres-why)

As the publication sates, “Claims that poverty has almost disappeared in India are misleading and take attention away from the lack of data on the extent of poverty in the country, a study has found.” It pointed to studies by three economists who used data from the Household Consumer Expenditure Survey (HCES) 2022–23 and recalculated the Rangarajan poverty line for each state and rural-urban area.

The Wire also pointed out that “The chief executive officer of Niti Aayog made a fantastic claim that the poverty ratio in India had fallen below 5% according to the 2022-23 consumption expenditure survey data. His claim was based on the fact that the per capita consumption expenditures of only 5% of the population in 2022-23 fell below the poverty-lines for that year for rural and urban India, arrived at by updating, on the basis of consumer price indices, the poverty-lines suggested for 2011-12 by a committee headed by Suresh Tendulkar.”

This was not the first time that Niti Aayog had played around with numbers. In August 2021, this author pointed out how Niti Aayog had put up some fanciful numbers for Uttar Pradesh, just before elections were held (https://asiaconverge.com/2021/08/the-fanciful-figures-of-uttar-pradesh/). It is no surprise, therefore, that many people take this think tank’s findings with a pinch of salt.

And then came news that India’s gold imports had reached an all-time high. As a Business Standard report put it, “According to revised data of the commerce ministry arm Directorate General of Commercial Intelligence and Statistics (DGCIS), gold import numbers have been slashed since April 2024, revealing excess imports of about $ 11.7 billion during the first eight months of 2024-25.

The revision was prompted by an unusual surge in imports of the precious metal in November 2024, leading to a record import of $ 69.95 billion and the highest-ever trade deficit of $ 37.84 billion. (https://www.business-standard.com/india-news/amid-error-in-gold-import-figures-panel-formed-for-accurate-data-reporting-125010901290_1.html).

Naturally, the emergence of such wayward numbers makes one wonder if the seriousness attached to data collation is up to the mark or not. The government’s failure to hold the 2021 Census has only causes such fears to gain traction. Data has begun to stretch credibility in ways that can only be described as being unhealthy.

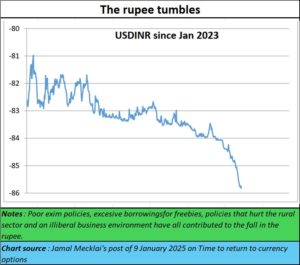

One of the most visible indicators of things going wrong is the way the Indian rupee has continued to fall. High interest rates (https://bhaskarr.substack.com/p/why-are-interest-rates-high), , high inflation, poor exports, and widening balance of payments, and large scale unemployment have all contributed to this fall in the value of the rupee. The inability of the government, over the decades to start producing goods aimed at meeting the requirement of countries who export to us, has only made us more dependent on these suppliers, eroding the very concept of equal trade. Unless a country can think proper export import policies, unless it learns to cultivate trade in the neighbourhood (watch ministers rush off to the west for every little reason, and ignore the pursuit of policies that could strengthen trade with Southeast Asia or China) can be quite depressing.

Conclusion

The concept of a Viksit Bharat must begin with working on improving the credibility of numbers emanating from the government. When credibility receives a body blow, the suspicion that the numbers are a fudge cannot be easily eradicated. Respect for numbers also means not concealing them. When government take away data from websites, when figures are constantly sought to be revised, or when any exercise to get numbers out is frustrated (the missing Census data is a good example), fears of a fudge being presented to people cannot be wished away.

India needs to get its act together. It needs to respect number collation and number presentation. And it needs to stop concealing numbers.

Can India do that? Or more importantly, will it?

——————

Do watch my latest podcast of interest rates at https://youtu.be/yIfOA1ZB1VU

COMMENTS