https://www.freepressjournal.in/analysis/policy-watch-two-cheers-not-three-for-the-agri-bills

A lot more needed to be done before tabling the agri bills

RN Bhaskar — 1 October 2020

The government finally made a move. It has introduced some path-breaking bills for the improvement of agriculture and the lot of farmers in the country. For that the government deserves two cheers.

The third is being withheld, because of several reasons. But first the reasons why the two cheers are warranted.

The government has abolished agricultural produce market committees (APMCs). It has freed the movement of agricultural produce from the farm to any mandi or place where the farmer may get a better price than what his neighbourhood offers. It has abolished the ceilings on storage of agricultural produce, thus allowing for more agri-warehouses to come up. It has legalised contract farming. And it has empowered sales of agri-produce through the e-NAMs or electronic national agricultural markets., In short, sales through commodity exchanges will now be encouraged.

The government has abolished agricultural produce market committees (APMCs). It has freed the movement of agricultural produce from the farm to any mandi or place where the farmer may get a better price than what his neighbourhood offers. It has abolished the ceilings on storage of agricultural produce, thus allowing for more agri-warehouses to come up. It has legalised contract farming. And it has empowered sales of agri-produce through the e-NAMs or electronic national agricultural markets., In short, sales through commodity exchanges will now be encouraged.

All these will certainly go a long way in empowering the farmer. Today, the small farmer is caught in a piquant situation. He buys his inputs at retail prices but is compelled to sell his produce at wholesale prices. This squeezes him from both ends. He pays more to begin the production cycle. And he gets paid less when he goes to the market. Allowing farmers to reach the end consumer will certainly help him get better prices – though over time. Gradually, you will find farmers contacting restaurants, dhabas, fast-food sellers, and striking up independent deals with them. Thus, the restaurant or the fast-food player will be able to get agri-produce directly from the farmer (hence at prices lower than they pay today). The farmer too could hope to get a better price.

But this is where the smiles should end.

Deal with poverty first

- At a time when the economy is going downhill, and unemployment is rife, there was a need to focus on both. The bill tends to dissipate energies. This is the time to hold the economy together, not create divisions. The timing of such regulations just before major elections (Bihar is a major agricultural state) muddies the waters. In fact, the new bills could see job destruction in the short run.

- What about implementation? Like the GST, the concepts behind the proposed regulations are laudable. But not much has been done about implementation of these regulations. Creating parallel transport system, cold storage, warehouses, owned by farmers, is the first imperative step. Now the farmers will have to use the same facilities that APMCs have. Self-defeating.

- Little clarity about the role of the FCI (Food Corporation of India) and SWCs (State Warehousing Corporations). Will both be debarred from purchasing rice and wheat directly from farmers? Will they be compelled to source their procurement through eNAMs? If yes, that will be wonderful. This will upset the revenue making plans of many big farmers, politicians, and middlemen – especially in Punjab, Haryana, and West Uttar Pradesh (UP). If FCI and the SWCs are not debarred from such cozy deals, the major benefits from these regulations will be lost. The money spent on rice and wheat procurement, the grains going rotten, the corruption and the collusive pricing will further drain India’s exchequer (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2020/05/atma-nirbhar-and-agri-markets/). It will be paid for by the taxpayer, but the benefits will go the large farmers and politicians (and greasy fingered officials of the procurement departments).

- The MSP (Minimum Support Price) concept needs further clarification. Do remember that MSP with procurement has been reserved only for rice and wheat and not for other crops. Occasionally, it has been extended to pulses. But this is not a permanent feature. Other grains – millets, other cereals like corn and maize – and pulses are out of the reckoning as far as procurement is concerned. Announcing an MSP without the benefit of procurement, makes the announcement a joke. If a trader refuses to pay the MSP, there is nothing that the farmer can do. The trader just does not lift the crop. The farmer sits on crops that could soon turn rotten and lose its value. He eventually sells it at a distress price. Commodity exchanges have recommended to the government several years ago, that the government should step in to purchase any grain or pulses if the market price go below the MSP (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2020/02/budget-2020-farmers-will-now-reap-govt-not-sow-agri-distress-continue/). The MSP then becomes the price benchmark with a safety net. It compels the trader to pick up the crop at those prices (or nearabouts). But the government has not done this. The new bills do not clarify the situation either.

- Contract farming ought to have permitted lease of farmlands for a maximum period of say three years. A clause could be inserted stating that the lease amount shall not be less than the average annual revenues garnered per acre from a region. This way, poor farmers would get an income without losing ownership of land. They can change their mind three years later. They also have the option of earning as farm labour. When land is taken on lease, disputes over contract farming are avoided. Today, it is difficult to enforce a contract if market prices go higher than contracted values, and the farmer chooses to sell his crop elsewhere. But when the farm is controlled by the grower, the disputes disappear.

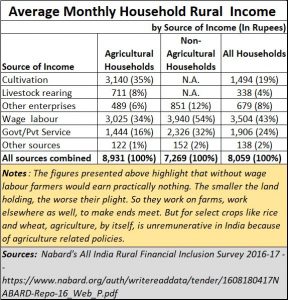

- Finally, study the table alongside. The farmer gets precious little from cultivation. Even animal husbandry, usually cattle milk, fetches him barely Rs.711 a month. Normally, even at Rs.26 a litre and a yield of 7 litres a day, the farmer should get Rs.4,500 a month for 25 days of milk production. He gets less, because states like UP, the largest milk producer in India, pay him only Rs.14-16/litre (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2020/09/india-plundered-again-by-tweaking-rules-against-prosperous-states-and-encouraging-profloigacy-irresponsibility/). That gives the farmer a surplus income of barely Rs.2 per litre. If the government had only made Rs.26 per litre compulsory for the country’s largest milk producing state, the farmer would have seen a five-fold increase in income. UP is a BJP ruled state. This law should have come first. Farmer incomes would have soared. The agri bills could have come later.

Pushing the agri bills before the milk pricing measure is putting the cart before the horse. India has a phenomenally successful cooperative milk model in place. Even responsible private sector players like Hatsun pay Rs.26 a litre. But UP exploits farmers. If farmers must be protected, start with UP’s milk producing farmers. Empowerment of farmers must begin from home.

There are other things the government should be doing to make agriculture healthier. But that will be dealt with in another article.

It is these missing parts that make the agri-bills a great concept, but pushed through with half baked measures, in the wrong sequence, and without the required clarifications. Now both farmers and traders will lose – at least temporarily. At a time when grain output is likely to be at an all-time high, and the economy is skidding down a slope, some sagacity should have preceded this move. Now, the resultant pain could be a lot greater than people imagine.

COMMENTS