Policy watch

Good listening is imperative for good governance

Rn bhaskar

The present government won a huge mandate from the people of India. One reason was that it promised to bring in good governance. But many people in the government forget one basic rule about governance. The first step towards good governance is good listening.

Listening takes place in many ways. It can be through the conventional way of a complainant approaching an officer to lodge his grievance. This can be through a personal visit, or through a phone call. Or it can be through a media report which demands redressal of a grievance. It can be through a written communication (usually through letters) that a complainant wishes to submit to an authority (and for which the law requires an acknowledgement to be given to the complainant). Or it can be through an email.

Listening takes place in many ways. It can be through the conventional way of a complainant approaching an officer to lodge his grievance. This can be through a personal visit, or through a phone call. Or it can be through a media report which demands redressal of a grievance. It can be through a written communication (usually through letters) that a complainant wishes to submit to an authority (and for which the law requires an acknowledgement to be given to the complainant). Or it can be through an email.

Nevertheless, despite the best intentions of Prime minister Modi, there are senior officials who try not to listen. One way is to inform the complainant that the “sahib is busy”. This ploy invariably prevents a complainant from meeting – or even speaking to — an official.

Then there is the customary police official who refuses to accept letters and acknowledge receipt. Their contention is that the letter is not in the right format. The policeman on duty then insists on writing out the complaint in the police register in a manner that suits the police. And, usually, the police insert words or even clauses that make the complaint weaker (or sometimes stronger when there is political backing) than the complainant would like it to be.

Fortunately, the courts have made it mandatory for the police to register first information reports (FIRs) promptly. The ability to while away time in writing down a complaint is thus reduced, and complainants nowadays do not have to wait for hours till their complaint is registered. Most police stations, however, do not normally accept letters.

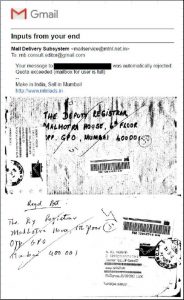

Then there are the brazen officials who actually refuse to accept letters. A good example is the office of the Deputy Registrar of Cooperatives in Mumbai. Its office routinely refuses to accept registered mail from postmen. When queried, the officer replies (or at least he did to this author) that his office does not accept registered mail. “If a complainant has some matter to complain about, he can seek an appointment, or personally deliver a letter,” he added. But appointments are not given easily. And letters brought in person are also not accepted. The good thing about refused registered letters is that there is proof of their not being accepted (see pix).

Then there are senior bureaucrats who refuse to hear complaints by ensuring that their email inboxes are full, and all mails sent there are bounced back. This is true even of senior managers of public sector units (see pix). Surely, if an official cannot manage his email inbox, should he be entrusted with the job he is supposed to carry out? This is another issue the government needs to address.

But the most crafty is the stratagem adopted by some bureaucrats (especially in Andhra Pradesh) where the email goes to a staging server. The complainant is informed that the email cannot be delivered and that that the service provider is still trying to deliver the email. Meanwhile, the bureaucrat checks his email on the staging server and ‘allows’ only some emails to reach his email inbox. The rest of the emails get bounced after 2-3 days with the message “I have given up trying. The email could not be delivered”.

Each of these methods violates a fundamental principle – that no complaint can be rejected without first receiving it and taking a look at it. Conventionally, it used to be letters. But the government’s rule book has not included emails as well. The penalty for refusing to accept letters (or emails) could be disciplinary action, resulting even in dismissal. But this rule has seldom been given effect. This is because the implementers of the rule book are bureaucrats themselves.

The irony is that these bureaucrats and ministers are disdainful about the very people who create the funds for their salaries and perquisites. They are actually telling people that their concerns do not matter. They forget that their first responsibility is towards the citizens they are meant to serve. Their complaints are the very reason why they are being paid. Unless that awareness and concern seep in, many callous bureaucrats and legislators will not even understand how critical and sacred the act of ‘listening’ is to good governance.

The disdain of bureaucrats (and legislators) can often be traced to the clause which does not allow a citizen to act against a government official (ostensibly to protect him from harassment, unless okayed by the state government or senior government officials. This incestuous loop of protection has made bureaucrats brazen. They protect the ministers, who in turn protect the bureaucrats.

It is only recently that the courts have begun questioning this immunity granted to both ministers and bureaucrats. On more than one occasion the courts have ruled that investigations can begin and charge-sheets can be filed without formal sanction of the council of ministers. That is a good sign.

The government should buttress this with suitable amendments in its rulebook allowing for summary dismissal of any officer who refuses to accept letters of complaint. Unless this is done, all talk of good governance will fall by the wayside.

Making bureaucrats listen is the first crucial step. Holding them accountable for actions taken (and not taken) should be the next step. Making them proactive and citizen-friendly will be the third. But the last two cannot be achieved, unless the first step in put into place.

So, is the government listening?

COMMENTS