R N Bhaskar

16 February 2015

Cities have their own charm. But each city has its own ugly underbelly too. In India that underbelly is the politics of vulnerability.

The game is played this way. Sell people a dream that the cities will make you rich. That they will make you earn enough money so that you can even send a tidy sum back home to your impoverished marginalised village.

Hook, line and sinker

Then when you bite the bait, you are told “This man will protect you. He will allow you to find a place close to your work – never mind if it is a hovel in a slum. But it is a place to stay in, right? In turn, you must vote for him. Okay?” That man is the protector. The slumlord. But even this slumlord does not protect you against some other people. And then the exploitation begins.

For some time, a partial protection is offered by the slumlord. But soon someone comes and threatens to throw you out unless you pay. You try and earn something as a hawker, and for that you must pay to more than one party. You try and set up a stall, and the number of people demanding payment multiplies. As you try climbing the slippery slope of unregularised existence in a city, you find that you make money, yes. But you pay for doing just anything, at each step. All in cash, without any receipt.

An irregular existence

Welcome to the world of irregular ‘regularisation’. It works with sex workers, with hawkers, with slum-dwellers and even with rag-pickers. It works with water connections, electricity metering and allotment of ration cards and gas cylinders.

And it works with all establishments too. The shops & establishments inspector visits each firm for his annual ‘collection’. The labour inspector can make things inconvenient for factories if he is not taken care of. The food and drugs inspector does the same with medical shops and with eateries. And the excise inspector does it with almost every shop, especially with liquor vendors and bars.

But there is a big difference here. Legal establishments are less vulnerable to exploitation compared to the all-pervasive but irregular existence of hawkers and roadside stalls.

All this happens mostly (but not exclusively) in metropolises, where vote banks and illegal establishments are encouraged. The biggest games are played in the three largest cities — Delhi, Mumbai and Kolkata.

In the beginning you accept it as the price to pay for climbing the slippery economic ladder, in the quest for stability and dignity somewhere or the other. But both remain elusive and their momentary acquisition can be quite fragile. That is when the phase of vulnerability and resignation begins.

The crusader

That is, till someone comes a-knocking with a promise of hope, dignity, and even the ability to fight back.

Narendra Modi did that when he stormed the country with his vision of progress and fair play.

And he dazzled everyone with his performance at the hustings. But then came Arvind Kejriwal with his razzmatazz and his equally alluring promise of slum regularisation, water and electricity. He too promises an end to this vulnerability.

Such promises work brilliantly in cities where populations live cheek-by-jowl, and everybody jostles for space. That’s where many migrant workers and irregular hawkers need the red light areas. But both remain unregularised. After all, how else will the policeman and the politician get their daily cake? The covetousness for illegal gains is irresistible.

Kejriwal’s biggest allure is his claim that he can compel the police (and others) to stop taking ‘haftas’ or bribes. And his resounding victory in Delhi has set off alarm bells ringing in Mumbai and Kolkata.

That’s understandable. Remember, only 20% of Delhi’s population stays in slums. In Mumbai, slum-dwellers account for almost 45% of the city’s population. Here, despite court exhortations, legislators have not yet worked out a way to legalise hawkers, penalise illegal parking, and clear pavements.

Kolkata too has over 30% of its people in slums, but in far more abject poverty than either Mumbai or Delhi.

And there are times when minorities too are made to feel vulnerable. Only this time they become low hanging fruit for any electoral crusader in shining armour. That is why most BJP governments in various states have been pushing through a Right to Services law to curb the ability of petty bureaucrats and law enforcement agencies to demand bribes in order to prevent delays in clearances.

But there is a catch here. True, the right to services is sorely needed. But regularisation of rights for slum-dwellers, hawkers and sex workers are even more desperately needed. India’s legislators will therefore have to discover ways to craft policies that actually redress these issues. Urgently.

Dangers lurk ahead

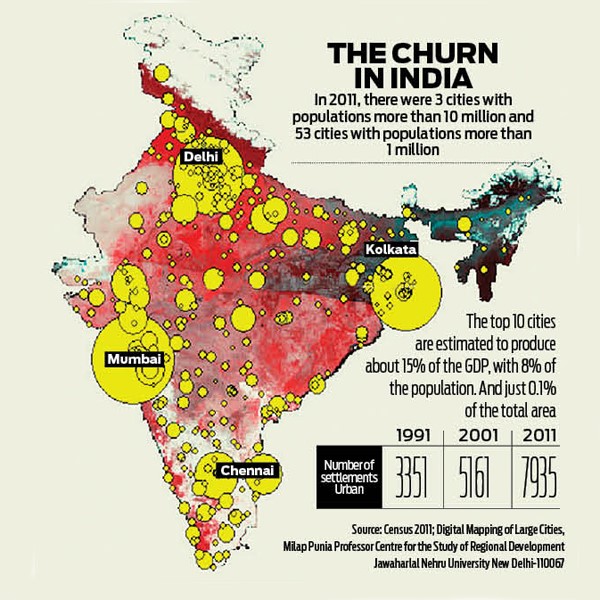

If not, the disaffection will soon spread to other cities and urban clusters. Watch the rise in these numbers. There were only 3,351 urban agglomerates in India in 1991 according to the Census.

This swelled to 5,161 by 2001 and then ballooned to 7,935 by 2011. Expect this number to keep growing during the coming years. And expect the number of cities with populations of more than 1 million to double in the next 4-5 years.

If any government hopes to remain in power, it will have to find ways to ensure that these new migrants to towns and cities and metropolises are not made to feel vulnerable. This will certainly be resisted by old fashioned legislators, bureaucrats, policemen and other law enforcers. But India is changing rapidly. And the tempo of change will become faster. But more on that next week.

The author is consulting editor with DNA.

Read the original article here.

More on India and its policies here.

COMMENTS