Why the Supreme Court’s intervention is crucial for saving Indian temples

Editor’s note: This is the second segment in a three-part series on Hinduism, godmen and the judiciary.

What is Hinduism?

One of the best definitions comes from the Supreme Court itself when it remarked: “Hinduism, as a religion, incorporates all forms of belief without mandating the selection or elimination of any one single belief. It is a religion that has no single founder; no single scripture and no single set of teachings. It has been described as Sanatan Dharma, namely, eternal faith, as it is the collective wisdom and inspiration of the centuries that Hinduism seeks to preach and propagate.”

This was recorded in their judgement by Justices Ranjan Gogoi and NV Ramana, Supreme Court judgement (Writ Petition (Civil) No 354 of 2006 of 16 December 2015.

On 6 January 2014, the SC pronounced a judgement on the role that governments should not play with temples (http://judis.nic.in/supremecourt/imgs1.aspx?filename=41133). It ruled that no government had the absolute right to take over the management of temple trusts. By implication it was also stating that the government takeover of temple trusts of Shirdi, Siddhvinayak, Vaishnodevi and even Tirupati were patently illegal and could be challenged.

The Supreme Court ruled that Article 26 of the Constitution confers certain fundamental rights upon the citizens which can neither be taken away nor abridged. The Court made this observation while deliberating over the case against the Tamil Nadu (TN) government, which wanted to take over the management of the Chidambaram (Nataraja) temple.

This order is extremely significant. It could reopen other temple cases as well. After all, ever since Independence, state governments, with a wink and a nod from the Centre, have coveted the power and the wealth that temple trusts have enjoyed.

This order is extremely significant. It could reopen other temple cases as well. After all, ever since Independence, state governments, with a wink and a nod from the Centre, have coveted the power and the wealth that temple trusts have enjoyed.

People still remember how NT Rama Rao, former chief minister of Andhra Pradesh, ‘nationalised’ the Tirumala Tirupati Devasthanams or TTD (Tirupati Trusts), which administer the famous conglomeration of temples, educational and social organisations under the Tirupati banner.

Of course, TN holds the distinction of having ‘nationalised’ most of the temples. There are instances where temple funds have been used to finance mid-day meals with the chief minister’s picture painted on the walls of the venue where these meals are served.

The government of Maharashtra similarly ‘took over’ the management of important Hindu shrines like Shirdi and temples like Siddhi Vinayak. It may be recalled that the state government wanted the temple to finance the funding of the airport strip that was to be built near the shrine.

But this had to be shelved after violent protests by devotees who objected the government trying to pass on what was a state expenditure to the temple trust.

Many other states have followed similar practices and have ‘nationalised’ temple trusts. In all cases, the trusts have been Hindu temple trusts. None of the religious trusts of other denominations and religions have been touched. Thus the Hindus have lost the most critical source of funding of community welfare programmes. The beneficiary has been the government which has prevented the Hindus from carving out a sensible vision for their own community.

As mentioned above, TN has the worst record. It today controls 36,425 temples, 56 mutts or religious orders (and 47 temples belonging to mutts), 1,721 specific endowments and 189 trusts. It has misused temple property, promoted politically expedient programmes using temple funds, and emasculated the mainstream religion in that state and even the country.

In the absence of the mainstream Hindu community having independent funding sources for its own vision, the vacuum has been exploited by politicians. They have propped up other godmen, who build their own community of devotees. They are allowed use of all the money they collect. And they eventually use their parish as a votebank for some leader or the other.

They thus erode the ability of a community to preserve its value system. They actually encourage ‘lumpenisation’ of the community, and later even of society.

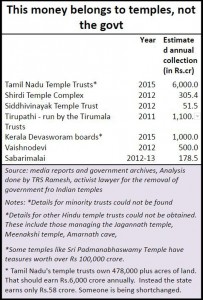

It is anguishing to watch temples and community values being thus degenerated (see chart/table).

Governments are known to have used trust properties for personal benefit. As a noted lawyer, TRS Ramesh, points out, TN’s temple trusts own 478,000 plus acres of land. That should earn Rs 6,000 crore annually. Instead the state earns only Rs 58 crore. Someone is being shortchanged.

A case in point is the Sri Kalapeshwar temple in Chennai, which gets a rental of just Rs 3,000 a month against the market rate of Rs 3 lakh. The difference is cause enough for a criminal investigation to be launched.

In the Chidambaram temple trust case, the Supreme Court noted that each time the lower courts passed an order, the state came up with a new order. This compelled the Trust’s Brahmin caretakers, often referred to as Dikshitars, to challenge these new orders. The state tried frustrating each court verdict with even newer orders. Finally, the matter reached the Supreme Court which reiterated that the provisions of Article 26 of the Constitution are inviolable.

As the court observed, “Even if the management of a temple is taken over to remedy the evil, the management must be handed over to the person concerned immediately after the evil stands remedied. Continuation thereafter would tantamount to usurpation of their proprietary rights or violation of the fundamental rights guaranteed by the Constitution in favour of the persons deprived. Therefore, taking over of the management in such circumstances must be for a limited period… Supercession of rights of administration cannot be of a permanent enduring nature.”

This order might go a long way in restoring to the majority community the right to govern itself. But it hasn’t till now. Even two years after the Court passed this judgement, no other temple trust has come forward. But this could possibly be because the present temple trustees are people known to be close to politicians. Clearly, till the devotees come together to file a case against the temple trustees, this might not happen.

Curiously, even the RSS, known to be espousing the cause of Hinduism, is unwilling to take up the issue of liberating the temple trusts from the government. Has even the RSS become collusive?

Time lines to the SC judgement:

The story of the government taking interest in temple trusts in India goes back to around the 1840s when the British government — unable to control temples — asked several prominent mutts(religious orders) to administer temples and endowments. This was because while a temple was located in one place, a devotee might have donated his lands located far away to the temple. It was difficult for the tax authorities to reconcile ownership of lands with temple managements.

In the 1920s, the local legislature in Madras State (much of which later became Tamil Nadu) passed the Madras Hindu Religious Endowments Act, 1923 (Act of 1925). This led to the setting up of a Hindu Religious Endowments Board (Board) with the object of providing for better governance and administration of certain religious endowments. Its validity was challenged.

By 1926, the Madras Hindu Religious Endowments Act 1926 – ACT II of 1927 was passed thus repealing the Act of 1925. This was subsequently amended several times.

By 1939 the Madras High court ruled that the Board cannot undertake the notification process (for takeover of temple trusts) on frivolous grounds.

By December 1951, after independence, the Madras High Court Division Bench passed twoorders questioning amendments and orders passed by the TN government in August 1951. Dikshitars (Brahmin priests and aretakers) are recognised as a religious denomination.

By 1954, the Supreme Court dismissed TN’s appeals as the state itself decided to withdraw the earlier notifications.

In 1959, the state introduced the Act of 1959, Section 45, which empowered the state’s authorities to appoint an Executive Officer to administer the religious institutions, but withsafeguards.

On 31 July 1987, the commissioner of religious endowments appointed an Executive Officer for the aministration of the Chidambaram Temple. The Dikshitars challenge this order by filing a writ petition. The High Court of Madras grants stay of operation of the order, but the writ petition was dismissed on 17 February 1997.

After several more attempts at the High Court of Madras, the Digshitars along with Subramaniam Swamy, member of Parliament, file a writ appeal with the Supreme Court — appeal No 181 of 2009, followed by a civil appeal No 10620 of 2013 contesting that Article 26 of the Constitution confers certain fundamental rights upon the citizens and particularly on a religious denomination which can neither be taken away or abridged.

On 6 January 2014, the Supreme Court upholds the contention. The apex court curtails the State’s right to administer temples.

Also read: Part I — Does Hinduism produce more godmen than other religions?

Next: Part III — The Supreme Court and its approach to religion in India

COMMENTS