http://www.firstpost.com/business/pulse-prices-crash-why-its-a-case-of-misdirected-focus-by-the-policymakers-3421912.html

Pulse of the nation – I

A story of misdirected focus, funds and fallacies

RN BhaskarMay, 04 2017 13:49:13 IST

The issue of pulses is high on every politician’s mind. There have been at least five statements on the issue of pulses in the Lok Sabha since the beginning of 2017. There is a rage among farmers because prices have crashed.

Had prices crashed because of domestic oversupply, that would have been a bit more bearable. Agricultural products in India are always subject to huge market price volatility. One reason is the enormous speculative appetite of traders who act as middlemen between the producer and the market. The second is the absence of any real commo90dity market. Each time the commodity market shows signs of maturing, the government comes in with a ban on trading oa agricultural products.

Had prices crashed because of domestic oversupply, that would have been a bit more bearable. Agricultural products in India are always subject to huge market price volatility. One reason is the enormous speculative appetite of traders who act as middlemen between the producer and the market. The second is the absence of any real commo90dity market. Each time the commodity market shows signs of maturing, the government comes in with a ban on trading oa agricultural products.

It is not as if the government does not have other weapons in its arsenal. It can always impose stiff margins to put the brakes on excessive trading. This is what SEBI allows the BSE and the NSE to do with stockmarkets. Or it can even resort to imports. Or it can dip into strategic reserves. However, it appears that the government’s favourite weapon is a ban on trading in that commodity. Hence commodity markets have remained stunted. But more of that in the last part of this series.

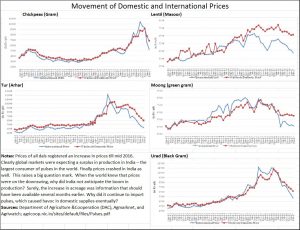

This time, the volatility in prices was on account of several factors. One is that when it comes to pulses, there is no real global market. The biggest consumers of pulses are Indians. When India’s pulses production goes up, international prices crash. When India begins importing, international prices climb. India is the market. And other countries grow puses with an eye on demand and production in India. But more of this later.

So when India’s pulses production goes up, prices in India crash. And anticipating a a slowdown in offtake, global markets too witness a crash in prices, because it knows that demand from Indian markets was bound to decline substantially. But more on imports later.

And this is where the farmers are justified in becoming livid. Everyone knew that acreage unde4r pulses cultivation had soared given the firm trend of upward prices movement. This was evident to India’s planners in mid-2016.

All the planners were aware of the bountiful monsoon season last year. Given both increased acreage and good rains, it was obvious – even eight months ago – that India’s pulses production would soar. Yet India kept importing pulses. The farmers have a right to know why?

The farmers are also sore that the government has continued to pamper wheat and rice growers with a procurement policy. They have begun asking why a procurement policy has not been extended to pulses.

A big relief for farmers was the government decision last fortnight to impose a 20% duty on pulses imports (http://smestreet.in/ram-vilas-paswan-hails-import-duty-hike-on-pulses/) . The other good news – for consumers – was that prices of pulses had begun to cool off. They would not have to cry themselves hoarse over pulses becoming more expensive.

Yet, farmers howled with fury when the centre informed state governments that it would not resort to mop up of pulses through procurement measures (http://www.mydigitalfc.com/news/centre-turns-down-maharashtra%E2%80%99s-plea-pulses-buy-865) It seemed as if policymakers have been anxious to make the right moves without rocking the proverbial agricultural boat in North India. Thus rice and wheat continue to be favoured with a procurement policy. Pulses have been ruled out for such a treatment.

North India is important. That is where the country has the maximum number of elected seats. That is where India has its wheat basin. And rice too – especially basmati – which is a major export earner and political funds grabber. Not surprisingly, many of India’s policies are directed towards wheat and rice, even it is to the detriment of the economy and to the very moral fibre of those who are in charge of agricultural produce procurement. But more of that later.

That is why this article is broken up into several parts. In addition to this introductory article there are four more parts.

Read on. . . . .

COMMENTS