http://www.moneycontrol.com/news/trends/current-affairs-trends/how-gnfc-is-reviving-the-glory-of-neem-2316943.html

Project Neem –I the second part can be found at http://www.asiaconverge.com/2017/07/gnfc-expands-its-neem-business/

GNFC triggers a neem revolution

Rn bhaskar – Jul 03, 2017 01:06 PM IST | Source: Moneycontrol.com

There are some concepts that have the potential of changing an entire country. And when these concepts are given the imprimatur of government policy, the consequences can be far-reaching. And if this has the benefit of entrepreneurial vision, the very industry begins to transform itself.

This is what happened with solar power, when Hermann Scheer decided to nudge Germany towards using this almost inexhaustible source of energy at the turn of this century (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2016/04/india-not-learn-germanys-hermann-scheer-solar-power-model/). This is what happened with Operation Flood, when Verghese Kurien decided to take charge of the concept, and got Lal Bahadur Shastri to allow him to be the helmsman at NDDB. Kurien then crafted a policy that propelled India towards becoming the world’s largest producer of milk (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2013/05/47/).

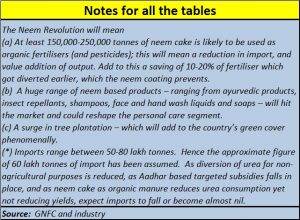

This is precisely what happened when prime minister Narendra Modi began talking about “Save Water; Save Energy; Save Fertiliser”. However, unlike, previous governments which only advocated the desirability of neem-coating urea, Modi made it compulsory. By May 2015, the policy mandating this technique was in place. Coating urea with neem makes it unfit for diversion to non-farm uses. And to fulfil this objective of the PM, GNFC stepped in to champion the neem project. As Dr. Rajiv Kumar Gupta) IAS, who took over as managing director, GNFC from May 2013, puts it, “We were rooted to agriculture, being a fertiliser company. We had ongoing CSR (corporate social responsibility) programmes already underway. We were confident that we could find a way to synergise both objectives and embrace the neem project.”

This is precisely what happened when prime minister Narendra Modi began talking about “Save Water; Save Energy; Save Fertiliser”. However, unlike, previous governments which only advocated the desirability of neem-coating urea, Modi made it compulsory. By May 2015, the policy mandating this technique was in place. Coating urea with neem makes it unfit for diversion to non-farm uses. And to fulfil this objective of the PM, GNFC stepped in to champion the neem project. As Dr. Rajiv Kumar Gupta) IAS, who took over as managing director, GNFC from May 2013, puts it, “We were rooted to agriculture, being a fertiliser company. We had ongoing CSR (corporate social responsibility) programmes already underway. We were confident that we could find a way to synergise both objectives and embrace the neem project.”

In many ways, GNFC has always tried to do something unusual, something novel, often venturing into areas where angels fear to tread (but more on this later). Ïmmediately, GNFC got about the business of identifying landless farm workers, particularly women. With the help of local tehsil officers and NGO groups, it began encouraging the setting up of self-help-groups – often comprising 10 women. Each of these groups was asked to collect neem seeds.

In many ways, GNFC has always tried to do something unusual, something novel, often venturing into areas where angels fear to tread (but more on this later). Ïmmediately, GNFC got about the business of identifying landless farm workers, particularly women. With the help of local tehsil officers and NGO groups, it began encouraging the setting up of self-help-groups – often comprising 10 women. Each of these groups was asked to collect neem seeds.

Luck too played its part. It was discovered that the time when neem trees begin dropping their seeds is between the end of April and the middle of June. That is when harvesting is over, and the new season for sowing seeds has yet to set in. Most landless labour goes to the cities in search of jobs and wages. The neem project was a godsend for them.

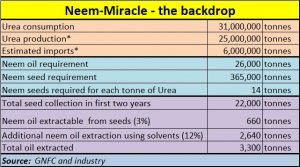

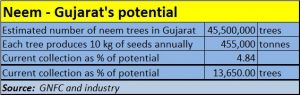

Neem trees grow in abundance in Gujarat. The last tree Census conducted in 2013 estimated some 45.5 million trees in Gujarat alone (some 4.5 lakh of them grow in Bharuch where GNFC is headquartered). These trees grow to maturity in 5-7 years, and enjoy a lifespan of around 200 years. And once grown, they give out around 10 kg of seeds on an average each year (though textbooks indicate a maximum potential of 50 kg per tree). These seeds are in the form of berries. The kernel is the seed.

Neem trees grow in abundance in Gujarat. The last tree Census conducted in 2013 estimated some 45.5 million trees in Gujarat alone (some 4.5 lakh of them grow in Bharuch where GNFC is headquartered). These trees grow to maturity in 5-7 years, and enjoy a lifespan of around 200 years. And once grown, they give out around 10 kg of seeds on an average each year (though textbooks indicate a maximum potential of 50 kg per tree). These seeds are in the form of berries. The kernel is the seed.

In any case, the neem tree (Azadirachta Indica) is not a stranger to Indians. It has been used as a traditional (Ayurvedic and Unani) medicine for more than 4,000 years. Many folk still use neem leaves around patients of small pox or chicken pox, convinced that its anti-bacterial qualities will make the passage of the disease easier and quicker. Most villagers still use the neem twig (dantoon) for a toothbrush and toothpaste rolled into one. Villagers mix neem leaves with clay to coat their walls because it is a known insect repellant. It has been used as an antiseptic, and (antiviral, antipyretic, anti-inflamatory, anti-ulcer and anti-fungal) medication. It is also used for restoring and maintaining soil fertility, which makes it highly suitable for agro-forestry.

In any case, the neem tree (Azadirachta Indica) is not a stranger to Indians. It has been used as a traditional (Ayurvedic and Unani) medicine for more than 4,000 years. Many folk still use neem leaves around patients of small pox or chicken pox, convinced that its anti-bacterial qualities will make the passage of the disease easier and quicker. Most villagers still use the neem twig (dantoon) for a toothbrush and toothpaste rolled into one. Villagers mix neem leaves with clay to coat their walls because it is a known insect repellant. It has been used as an antiseptic, and (antiviral, antipyretic, anti-inflamatory, anti-ulcer and anti-fungal) medication. It is also used for restoring and maintaining soil fertility, which makes it highly suitable for agro-forestry.

These seeds are now picked up by women, and then supplied to the local centre. One such woman is Jamnaben, who used the money from collecting neem seeds and buttressed by agricultural loans to buy a buffalo. Now she has two sources of income.

When GNFC started, it began paying them around Rs.6 per kg of seeds deposited with the local collection centre. A year ago, GNFC upped this price to Rs.7.5. Within the first two years, the company had generated a cumulative sum of Rs.25 crore as supplementary incomes to around 225,000 people, especially women and landless labourers. A third-party assessment conducted by UNDP on the socio economic impact of the Neem Project on women beneficiaries, confirmed that the project empowers the weak, especially women; creates value; and brings about a sustainable transformation of both society and business.

When GNFC started, it began paying them around Rs.6 per kg of seeds deposited with the local collection centre. A year ago, GNFC upped this price to Rs.7.5. Within the first two years, the company had generated a cumulative sum of Rs.25 crore as supplementary incomes to around 225,000 people, especially women and landless labourers. A third-party assessment conducted by UNDP on the socio economic impact of the Neem Project on women beneficiaries, confirmed that the project empowers the weak, especially women; creates value; and brings about a sustainable transformation of both society and business.

This year, GNFC has raised the price to Rs.10. Significantly, it has spread the world that it will maintain this floor price – and even pay more should conditions warrant – for the next three years. The idea is to ensure that more landless workers enlist for neem seed collection, and also encourage more people to plant neem trees. Gupta expects to persuade women in the neighbouring states of Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan to growing neem tries as well, and thus add to the seed collection mission. “We have set a target of at least a million trees in the next three years,” he adds. This could become the biggest tree planting drive in India, with multiplier benefits as well.

This year, GNFC has raised the price to Rs.10. Significantly, it has spread the world that it will maintain this floor price – and even pay more should conditions warrant – for the next three years. The idea is to ensure that more landless workers enlist for neem seed collection, and also encourage more people to plant neem trees. Gupta expects to persuade women in the neighbouring states of Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan to growing neem tries as well, and thus add to the seed collection mission. “We have set a target of at least a million trees in the next three years,” he adds. This could become the biggest tree planting drive in India, with multiplier benefits as well.

The collection centre in Jamnaben’s area is run by Amishaben, who checks the seeds, separates pebbles and sand from them, weighs them, sends the seeds and ensures that the women get their money. Her earnings have allowed her to set up a papad plant.

The seeds are then taken to the district collection centre where they are filtered once again, repacked in sacks and stacked for 3-4 months with care to ensure that they don’t suffer from fungal growth. The idea is to allow them to dehydrate naturally so that moisture in not more than 10% (artificial drying techniques damages the active ingredient in the neem oil) – watch the video at https://youtu.be/e6t1yYlhhEw .

The seeds are then sent for crushing. Typically, neem oil got this way accounts for just 3% of the neem seeds by weight. By using solvents, another 12% can be extracted. But pure neem oil – which currently sells for Rs.400 per litre – has around 400 ppm of the active ingredient. The oil that is extracted through the solvent process has one fourth of the active ingredient that the crushed oil has. However, since few know the difference, conventional traders have often palmed off the second for the first. Unfortunately, many unscrupulous businessmen just use leaves and the bark of the tree and get products with the neem flavour and taste. They pass these off also as neem products.

Much of this sub-standard oil is purchased by unsuspecting customers – and this includes some fertiliser companies as well. Gupta has now enlisted the support of forensic laboratories in agricultural universities in Gujarat to come up with standards and ways to determine the genuineness of neem products, especially neem oil. He is confident of producing enough oil to cater to the needs of all the fertiliser units in the country, and has also embarked on a major expansion of neem based activities. But more on that in the next part.

COMMENTS