http://www.moneycontrol.com/news/india/budget-2018-focus-on-healthcare-is-good-but-dont-degrade-the-quality-2497317.html

Budget 2018: Healthcare is needed, but where are the doctors?

According to the plans announced by Finance Minister Arun Jaitley during his Budget presentation, each family is covered under the new National Health Protection Scheme.

The three issues where India desperately needs a focused improvement are judicial redressal, education and healthcare. It is heartening that the current budget does take a very close look at the third. If the government has its way, it wants to the new medicare provisions to cover as many as 100 million families, Given India’s population of 1.3 billion people, which in turn means around 350 million households (assuming an average of four people per family), the Budget announcement effectively means that almost one-third of the people in India will be covered by some form of decent medicare.

According to the plans announced by Finance Minister Arun Jaitley during his Budget presentation, each family is covered under the new National Health Protection Scheme (NHPS). That would allow them to get medical reimbursement for treatment at hospitals up to a maximum of Rs. 5 lakh every year. The flagship health care scheme could become the world’s largest government-funded health programme — Ayushman Bharat Programme. As the finance minister put it, “We are slowly progressing towards universal health coverage,” which could easily become the “world’s largest healthcare programme”.

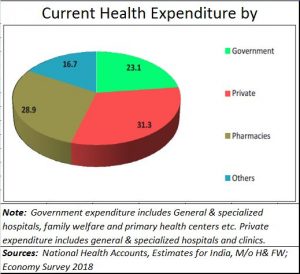

In fact, as recent surveys have shown, healthcare remains one of the key issues which people are quite concerned with (see chart).

According to Jaitley, who was greeted with loud thumping of tables in the Lok Sabha, this scheme alone could cover as many as 500 million people. This was certainly an improvement over the previous health cover the government had provided, but which had a cap of Rs. 30,000 cap on reimbursement. Citing a national survey report, the Economic Survey had pointed that people had to spend an average Rs. 26,000 for treatment per hospitalised case in private facilities.

According to Jaitley, who was greeted with loud thumping of tables in the Lok Sabha, this scheme alone could cover as many as 500 million people. This was certainly an improvement over the previous health cover the government had provided, but which had a cap of Rs. 30,000 cap on reimbursement. Citing a national survey report, the Economic Survey had pointed that people had to spend an average Rs. 26,000 for treatment per hospitalised case in private facilities.

The health care programme announced by the government is a very welcome step. This is because one medical emergency is enough to bankrupt a middle or small income family. It also gives a major impetus towards safeguarding the “demographic dividend” that India enjoys.

The health care programme announced by the government is a very welcome step. This is because one medical emergency is enough to bankrupt a middle or small income family. It also gives a major impetus towards safeguarding the “demographic dividend” that India enjoys.The announcements are good. But the big question is — where are the doctors? The government’s initial move to regularise homeopath and ayurvedic doctors to practice allopathy is both misplaced and pathetic. True, the aspirant homoeopaths and ayurveds have to go through a bridge course. But that is like telling all court clerks that they can become judges by going through a bridge course.

Will the legislators allow such bridge course doctors to practice on AIIMS on the families of bureaucrats and ministers?

The solution lies in two measures:

- Allow more medical colleges to begin operations, thus ending the licence raj for starting such institutes. The government should focus on outcomes and standards of passing graduates only. This could be done in the form of an exit examination each year for all medical graduates – almost along the lines of the JEE, an entrance examination for engineering colleges. Such a move would reduce the practice of substandard education being imparted in medical colleges, and also also create more medical practitioners each year, which in turn could become another potential manpower export opportunity for India.

- Make it compulsory for all medical students to spend at least six weeks each year in rural areas at these health centres. Promotion to the next year will be dependent on completing this six month course. Only then will the government be able to man these rural health centres, and bring down the cost of medicare. It is like drafting youth into the army. Medical students have to be drafted into helping health care centre.

The budget does not allow for starting either new medical colleges or make rural practice for medical students compulsory. Instead, it wants to devalue medical education by allowing non-allopathic students to get regularised into allopathic practice. This leads to corrosion of standards in medicare. What is worse is that these sub-standard skills are allowed to practice in rural areas, which means that poorly qualified doctors are meant for the poor not for the powerful and the privileged.

This is similar to the provision the previous government made allowing ministers and civil servants at the level of secretaries to send their relatives to hospitals overseas for medicare. Fortunately this move (presumed to be introduced to benefit the ailing mother of a senior bureaucrat) was not put into effect. It would have effectively told the entire country that doctors and medical centres in India were not good enough for the powerful and the privileged.

The move to convert non-allopathic doctors to allopaths – after a bridge course – is similar to the ill-advised move made earlier.

COMMENTS