https://www.moneycontrol.com/news/india/comment-death-with-dignity-is-now-legal-2524935.html

The Supreme Court defends death with dignity, even as the legislature fails in its duty

The apex court has allowed passive euthanasia, but wanted strict guidelines to govern passive euthanasia when it is permitted.

“A calf, having been maimed, lay in agony in the ashram and despite all possible treatment and nursing, the surgeon declared the case to be past help and hope. The animal’s suffering was very acute.

In the circumstances, I felt that humanity demanded that the agony should be ended by ending life itself. The matter was placed before the whole ashram. Finally, in all humility but with the cleanest of convictions I got in my presence a doctor to administer the calf a quietus by means of a poison injection, and the whole thing was over in less than two minutes.

“Would I apply to human beings the principle that I have enunciated in connection with the calf? Would I like it to be applied in my own case? My reply is yes. Just as a surgeon does not commit himsa when he wields his knife on his patient’s body for the latter’s benefit, similarly one may find it necessary under certain imperative circumstances to go a step further and sever life from the body in the interest of the sufferer”. Mahatma Gandhi on the Right to Die with Dignity — (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2011/03/512/)

A five-judge constitution bench of the Supreme Court finally ruled on a petition filed by Common Cause – an NGO – for making the Living Will legal. The Society for the Right to Die with Dignity or SRDD (of which the author is Honorary Secretary) was a co-intervenor to this petition.

The apex court stated that human beings have the right to die with dignity. It allowed passive euthanasia, but wanted strict guidelines to govern passive euthanasia when it is permitted. The order was passed today by a five-judge Constitution bench of Chief Justice (CJI) Dipak Misra and Justices AK Sikri, AM Khanwilkar, DY Chandrachud and Ashok Bhushan .The judges gave four separate opinions. However, all of them were unanimous that a ‘living will’ should be allowed. They said that no individual should be allowed to continue suffering in a vegetative state when the person did not wish to continue living.

The top court on Friday also set in place strict guidelines for carrying out the mandate of a ‘living will’. The court did this by specifying who was authorised to effect it. The court also talked of involving a medical board to determine whether the patient in a vegetative state could be revived or not.

The top court on Friday also set in place strict guidelines for carrying out the mandate of a ‘living will’. The court did this by specifying who was authorised to effect it. The court also talked of involving a medical board to determine whether the patient in a vegetative state could be revived or not.

The SC said it was aware of the pitfalls in giving effect to ‘living wills’, considering the property disputes relatives have.

In doing so, once again it was the apex court which had to step into an area that the legislators had ignored. Like with the decrimininalisation of homosexuality, the need to reverse the ban on transportation of buffaloes for slaughter, this judgement also reaffirms the role of the apex court in areas which the legislature had chosen not to deliberate on. In fact, what is worse is that despite worsening healthcare indicators, India’s legislators wanted to usurp the right to life, without providing people the means to make life meaningful through proper medicare. — (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2018/02/budget-2018-and-healthcare/),

While the actual copy of the judgement was not available at the time of going to press, the background to the entire case is worth a mention.

Prior indications

The first time when the Supreme Court referred to the Living Will was in 2011 when the apex court was called upon to decide whether Aruna Shanbag, a nurse at KEM Hospital in Mumbai, who eventually died in May 2015, should be allowed to die a peaceful death instead of being kept alive through external support mechanisms.

The second time was when the government itself – through the Law Commission — put across a paper titled “Passive Euthanasia – A Relook. Report No.241. AUGUST 2012.”

The latest judgement puts the entire debate to rest.

The Aruna Shanbag case

The Supreme Court first touched upon the Living Will and Passive Euthanasia on March 7, 2011, when deliberating on the vexatious issue of whether Aruna Shangag should be allowed to die. Towards the end of Para 9, the Supreme Court stated (www.supremecourtofindia.nic.in/outtoday/wr1152009.pdf) that the issues under consideration were

“1) We have no indication of Aruna Shanbaug’s views or wishes with respect to life-sustaining treatments for a permanent vegetative state (PVS)

2) Any decision regarding her treatment will have to be taken by a surrogate.

3) The staff of the KEM hospital [who] have looked after her for 37 years, after she was abandoned by her family. We believe that the Dean of the KEM Hospital (representing the staff of hospital) is an appropriate surrogate.

4) If the doctors treating Aruna Shanbaug and the Dean of the KEM Hospital, together acting in the best interest of the patient, feel that life sustaining treatments should continue, their decision should be respected.

5) If the doctors treating Aruna Shanbaug and the Dean of the KEM Hospital, together acting in the best interest of the patient, feel that withholding or withdrawing life-sustaining treatments is the appropriate course of action, they should be allowed to do so, and their actions should not be considered unlawful.”

Implicit in para (1) above was the thought that if Aruna Shanbag had left behind a Living Will, things could have been different on determining the course of treatment. But the court refused to state categorically that the Living Will had legal sanction. Items (2) and (3) above would imply that if she herself had appointed a surrogate (by durable power of attorney for health care, when she was mentally fit) to take decisions on her behalf, the court would have respected the decisions of such a surrogate. However, in the absence of a Living Will and a Durable Power of Attorney for healthcare, the Court believed KEM Hospital dean would be an appropriate surrogate.

The Living Will

The Living Will is nothing but an advance directive – made legal in many countries. It is a directive to the medical fraternity on what steps to take – or avoid – when the person concerned is in a coma or is unable to expressly spell out the course of treatment that should be permitted for himself.

It is based on a simple premise that every mentally competent individual has the right to decide what treatment to accept or reject Will (a sample can be downloaded from http://www.asiaconverge.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/SRDD_Living-Will_revised.pdf). . Thus even if I have a tumour which could be life threatening, and I refuse to take the treatment my doctor recommends for me, I am within my right to refuse such recommendations. This right remains undiminished even if I were to die because of my refusal to accept the recommended line of treatment.

But the situation changes when I am not mentally competent to decide or express my decision (e.g. because of dementia, PVS or coma). At that point of time, the state takes over, and the doctors are free to treat me the way they wish. If my relatives and friends protest, and refuse the recommended line of treatment, they could be held as abettors in hastening my death.

It is to prevent such a situation that many countries have allowed patients to prepare an advance directive or Living Will (a sample can be downloaded from . It outlines the treatment a patient will accept or reject in case of inability to express this wish. To give it more teeth, many doctors and lawyers even recommend that in addition to the Living Will, the person may execute a limited power of attorney appointing a surrogate (relative or friend) authorizing him/her to take healthcare decisions on behalf of the person. Thus the advance directive can be a Living Will and/or Durable Power of Attorney. It authorises someone to ensure that the patient’s wishes are respected even when he is unable to take decisions or express them

If you look at this logically, the Living Will and Durable Power of Attorney do nothing more than arming a person with the same rights he had when he was mentally competent and articulate, hence the name Advance Directive. It asks for nothing more and nothing less.

Already legal in many advanced countries

For this author, the Living Will is nothing but an extension of autonomy, the rights a person already enjoys when mentally competent. It only allows him or her to spell out clearly – in the presence of a witness – what line of treatment he/she would like to accept/reject once the person is in a state where such a wish cannot be expressed.

Passive euthanasia authorises doctors to allow a terminally ill person to die by not doing something that is necessary to keep the patient alive or by withdrawing something that is keeping the patient alive.

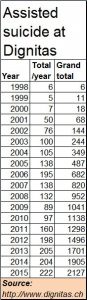

Many countries have already permitted voluntary euthanasia and/or physician assisted suicide, not just passive euthanasia. The most prominent agency offering this legal facility is Dignitas in Switzerland . In this country, with the help of Dignitas, a terminally ill person of any country – but one who is mentally competent – can get peaceful exit with physician assisted suicide.

At Dignitas, the doctors examine the patient, so does a psychiatrist. If they conclude that the patient indeed faces no cure from pain and misery, it helps the patient to end his or her life. Swiss laws permit this. Many other countries too permit this (including Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg and several states in the US. And despite alarmist forecasts that such measures would open the floodgates to suicides, the track record at Dignitas shows that this hasn’t really happened (see chart).

Febrile objections

Some people (including some of the judges of the Supreme Court) fear that both the Living Will and Passive Euthanasia can be misused.

Respectfully, this author believes that anything can be misused – a matchstick, a knife, a scalpel, an icepick – the list is endless. Civilisations grow stronger when ways are found to prevent misuse, and not by resorting to bans. When fears are allowed to become bans, a civilization moves towards ossification, even fundamentalism. In fact, going by media reports, this author is surprised that the apex court wants to lay down the strictest conditions to prevent misuse of the Living Will.

The author needs to remind the legislators and the judges that such strict conditions were not required when it came to organ transplants, where too doctors have the right to decide on the death of a person.

THOA 1994

India already has in place The Transplantation of Human Organs Act 1994 (THOA 1994). This act legalises ‘brain death’, even when heart and lungs are working, (for making removal of organs possible after proper consent). Within a span of 6 to 24 hours a team of 4 specialists examine the brain dead individual and certify brain stem death. Thereafter, organs of an individual can be used for transplantation to other waiting patients. Thus the certification process does not take more than 24 hours.

If euthanasia can be misused, so can THOA 1994. A patient in coma, who is not brain dead, may be declared brain dead by unscrupulous elements in society. The remedy lies in trust, good processes, appropriate safeguards and stringent punishment for any violation of the law.

Thus, the method the Supreme Court approved in the Aruna Shanbag case has resulted in almost no requests for passive euthanasia. The process is cumbersome and may take weeks or even months. The author fears that a similar situation may occur if the court imposes too many conditions for passive euthanasia.

But THOA has permitted families of brain dead persons to donate organs of the deceased to save many lives. The prescribed procedure for passive euthanasia is for a petitioner to approach the court with a request for allowing a patient to die. The court then appoints a panel of doctors, when then goes back to the court with its findings. The court then allows for passive euthanasia, or rejects the petition. That could take months, even years.

One cynical reasoning is: THOA 1994 benefits recipients (which may include politicians and judges as well). Hence its processes have been simplified. Passive euthanasia or the Living Will benefits nobody but the patient, and maybe those who have to look after him/her. Hence the urgency for easing the processes has been ignored.

In fact, it is a well-known fact that passive euthanasia is being carried out in most hospitals in India. Humane doctors treating such patients, where there is no hope of recovery, discuss with the relatives of the patient about futility of any further treatment. If the relatives agree, the patient is allowed a peaceful exit. On hospital records it is shown as natural death. Ideally, the procedure for obtaining legal sanction for euthanasia should be made simple and speedy (as in the case of certifying a person brain dead under THOA 1994).

In conclusion, one needs to highlight the views of the legendary heart surgeon Dr. Christian Barnard in his book ‘Good Life, Good Death’: “I have learnt from life in medicine that death is not always an enemy. Often it is good medical treatment. Often it achieves what medicine cannot achieve – it stops suffering.”

One hopes that the courts will concur as well.

COMMENTS