https://www.moneycontrol.com/news/business/economy/opinion-brace-yourself-for-an-economic-slowdown-3401971.html

A severe economic slowdown is likely to hit India. . .unless

RN Bhaskar – 18 January 2019

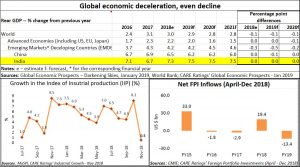

The recently released World Bank report on January 8 2019 (https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/31066/9781464813863.pdf ), confirmed what most people had suspected all along. The World Bank estimates the work economy to shrink by -0.1 % in 2019, and the decline could continue well into 2020 as well.

Part of this could be attributed to the Donald Trump factor – free trade is being threatened like never before. But it is also because the world has been awash in cash after 2008. Any attempt to bring back financial sobriety will mean a bit of belt tightening, and hence an inevitable slowdown.

Part of this could be attributed to the Donald Trump factor – free trade is being threatened like never before. But it is also because the world has been awash in cash after 2008. Any attempt to bring back financial sobriety will mean a bit of belt tightening, and hence an inevitable slowdown.

To that extent, India too will be no exception. It will witness barely any growth in 2019, and its economy could see a s negative if the recent downgrading of its GDP growth numbers from 7.5% to 7.2% turn out to be true.

This slowdown comes on the heels – for India – on the cusp of a general election. As pointed out earlier, this country tends to slow down expenditure immediately after elections (https://www.moneycontrol.com/news/business/economy/opinion-brace-for-economic-slowdown-after-2019-lok-sabha-polls-3289271.html). This election should also be no different.

By the time a new government comes to power, much money will already have been spent. But more worryingly are the amounts that will have to be spent – on Ayhushman Bharat, on reducing farm distress, and on creating jobs. The freebies may crowd out other demands for funds. That could worsen the slowdown for India.

Already there are indications that at least two states –Madhya Pradesh and Punjab – won’t even be in a position to honour their loan waiver commitments (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2019/01/nothing-quiet-farm-loan-waiver-front/). Then there is the spectre of power sector loans, caused by both errant entrepreneurs as well as state power grids.

What could be most painful will be India’s desperate efforts to boost exports at a time when most countries in the world will not be willing to import. At the same time, the country will be caught in the pincer grip of rising imports on the one hand and the unwillingness of foreign investors to come into India. As the chart shows, FPI (foreign portfolio investments) have declined. So have foreign direct investments.

So are we headed back to 1990? That may not happen. Things may not reach that state because, unlike 1990, India’s foreign exchange reserves are reasonably high. But the bank NPA nightmare continues to hover overhead – notwithstanding the RBI’s attempts to restructure MSME loans. That could actually worsen the problem as it would be akin to kicking the can further down the street. The banking wounds may begin to fester.

India will have to find some way out. It will either have to increase exports (which is difficult), or reduce imports (possible).

Many people believe that imports cannot decline; that they will only continue to climb. This author disagrees. Imports can be reduced, especially the country’s bills related to oil and gas. If India adopts on a war footing both rooftop solar (http://www.moneycontrol.com/news/business/dear-pm-modi-heres-how-bureaucrats-are-planning-to-scuttle-your-rooftop-solar-employment-plans-2468501.html) and waste to energy programmes https://www.moneycontrol.com/news/business/economy/comment-the-spinoff-from-swachh-bharat-wealth-from-waste-could-be-big-sht-2556797.html), it could achieve two major objectives. It could create over 80 million jobs. It could also reduce the country’s import bills drastically.

But one cannot promote solar power aggressively with a safeguard import duty of 25%. Nor can you promote the use of batteries with an 18% GST (down from an even more horrendous 28% earlier). These tariffs will have to be brought down to more realistic levels.

There are two more things that the government could do in these difficult times. The first, is to focus on affordable housing in very large numbers. It must build at least a couple of million houses each year to cope with the shortage of over 20 million homes (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2018/12/india-2019-govt-should-propel-growth-in-infra-renewable-energy-sector-to-ease-unemployment-pain/).

Building houses – as Iran discovered 20 years earlier – has two advantages. First, it uses things that are easily available domestically – labour, land, water, cement and steel. There is little dependence on imports. Second, it creates jobs.

With emplment comes purchasing power, and with that comes the kickstarting of economic growth. The rooftop solar has the potential for around 80 million jobs in a couple of year; affordable housing can create around 10-20 million jobs. But for affordable housing to succeed, the numbers must be large enough to prevent black-marketeering of such homes (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2018/12/india-2019-govt-should-propel-growth-in-infra-renewable-energy-sector-to-ease-unemployment-pain/).

But embarking on such a strategy will require both political will and sagacity. Will India’s legislators be able to demonstrate both qualities? Fingers crossed.

COMMENTS