https://www.moneycontrol.com/news/business/economy/budget-2020-to-fix-the-slowing-economy-begin-with-agriculture-4810561.html

Pre-Budget #1

Economic revival must begin with agriculture

RN Bhaskar — 13 January 2020

Another Budget season is just round the corner. The finance minister and even the prime minister are determined to show that they can introduce measures that can revive the economy. There are talks about tax sops and financial incentives. But none of them will go very far if the basics are ignored.

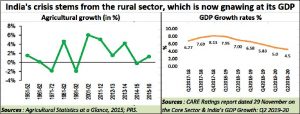

After all, the economy is hurting real bad (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2019/12/the-economy-is-hurting-real-bad/), And to understand the reasons behind the pain, it is essential to understand why farms matter immensely.

After all, the economy is hurting real bad (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2019/12/the-economy-is-hurting-real-bad/), And to understand the reasons behind the pain, it is essential to understand why farms matter immensely.

First, remember than over 50% of India’s people depend on the rural economy. And that means agriculture. Irrespective of the contribution of the agricultural sector to India’s GDP, the sheer scale of population requires any government to pay heed to the wellbeing of this sector and to make it sustainable – not through doles, but through policies that make this sector healthy.

Second it is important to note that unlike all the Asian tigers – including China, Korea, Taiwan, Singapore among others – India is not an export driven market. It is a consumption driven market. Thus when you have 50% of India’s population of 1.3 billion people in rural areas, this becomes a critically important consumption market – especially for things like motorcycles, tractors, harvestors, seeds, fertilisers and nutrients and a host of consumer goods.

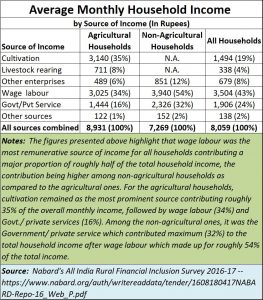

Third, hitherto, except for a brief period when Lal Bahadur Shastri tried to promote agriculture (and coined the slogan Jai-Jawan-Jai Kisan), successive governments have short-changed agriculture. As a result the farmer earns pathetically little from agriculture, as Nabard studies (see table) have shown (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2018/08/rural-incomes-worse-previously-imagined/).

Therefore, if the economy has to be revived, agriculture needs some key inputs. Here are some suggestions.

Therefore, if the economy has to be revived, agriculture needs some key inputs. Here are some suggestions.

First, one reason why the farm sector’s contribution to India GDP is just around 14% is because the farmer is allowed to earn very little for his produce. Leave alone milk where, thanks to Verghese Kurien, the farmer can earn as much as 80-85% of the market price for the milk he produces (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2016/03/significance-of-the-dairy-industry/). Similarly keep aside the politically pampered rice and wheat crops where the Food Corporation of India (FCI) guarantees procurement from most large farmers and thus gives them a remunerative price (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2018/08/farming-politicians-pricing/). Ditto for politically protected crops like sugarcane, and plantations.

But take the rest of the agricultural sector and you discover that when it comes to vegetables and fruits, the farmer earns barely 10% of the market price for his produce. With other non-procurement products, the farmer is lucky if he gets 30% of the market price for his produce. As a result, the farmer’s purchasing power has remained poor (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2018/08/farmers-in-india-dont-earn-much-many-are-terribly-exploited/).

If the government wants the farmer to earn more, it must make provisions for him to earn a better price. That can be done in two ways. For crops other than vegetables and fruit, the gove3rnment can actually get the FCI intervene in the commodity markets and offer to pick up any crop at the declared Minimum Support Price (MSP). Typically, even if 5% of the produce is picked up buy the FCI, traders will increase their price offering and provide the farmers a better price. Alternatively, the government has to immediately allow the farm sector to create an autonomous body like the NDDB, which comes in as a market maker. Unless the farmer can get 50% of the market price for his produce, the farmer will remain exploited. Doles are counter-productive, as they teach farmers to depend more heavily on the government. That will make them more vulnerable. In fact, both the NCDEX and the MCX and their affiliates had made similar suggestions to the government some years ago. But the government hasn’t done anything, not even in its last interim budget (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2019/02/the-interim-budget-is-good-politics-but-worrisome-economics/).

The second thing that the government can do is to announce — as part of the budget proposals — that anybody trying to stop a meat wagon will be imprisoned for a period of not less than three years. Meat kept by the roadside, in Indian conditions, becomes unfit for human consumption in a few hours. The madness unleashed by the gau-rakshaks has hurt farmers, cobblers and the meat industry very badly. The farmer has been the worst affected.

Let’s leave aside cows for the moment. If the cow is to be protected, so be it. But why touch buffalo meat? Most farmers are already moving to adopting buffaloes instead of cows for two simple reasons. First, buffaloes are not considered holy, so they can be sold to the trader – for onward sale to slaughter houses – without any qualms. Second, buffalo milk has more fat content. That fetches farmers more money per litre of milk produced.

But when a buffalo stops lactating, it must be sold. The cost of maintaining a barren or old buffalo is crippling. The farmer normally gets Rs.20,000 per old buffalo. To this he adds another Rs.20,000 and purchases a young milch buffalo. If the trader refuses to purchase the old buffalo from the farmer — because his consignments can get seized by crazed gau-rakshaks — then the farmer loses his ability to procure fresh cattle heads. That reduces his income, and increases his expenditure. And, in turn, the scare to take away old buffaloes affects the leather industry and the cara-beef industry – both major employment and forex generators (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2017/12/gujarat-elections-hindutva-beef-ban-may-actually-hurt-bjp/). The minimum estimated loss on account of this could be over Rs.23,000 crore a year

The third thing the finance minister can do is to take away the power to import agri produce from the hands of the bureaucrats and to leave such powers with farmer groups. Imports cause domestic price3s to fall. That hurts farmers. When domestic prices go up – as with onions – let the farmer body import, but sell it at normal market prices, not at less than market prices. That is what NDDB was taught to do under Kurien.

You cannot protect consumers forever. The farmer is a producer, and must also be protected. It is insensitivity to such a requirement that actually emboldened some bright boys in the government who thought that they could allow New Zealand to divert 5% of its non-liquid milk dairy produce exports to India. Thanks to a spirited resistance put up by farmers, this move was dropped (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2019/08/indian-bureaucrats-forgot-to-protect-indian-milk-from-imports/). The same thing happened a few years ago, when import of pulses was resorted to (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2017/05/how-pulses-imports-drove-domestic-growers-to-the-ground/). Such madness should be avoided.

Unless such situations are remedied, the farmer loses income, hence purchasing power. And, as a consequence, the wheels of the economy have grist thrown in them.

Can the finance minister usher in these measures for the sake of economic revival? It would go a long way towards fulfilling the prime minister’s promise of doubling farmers’ income. It must be said that even this assurance is too little because a doubling of 10% is still 20%, far below the 50% desired level.

COMMENTS