https://www.freepressjournal.in/analysis/policy-watch-msp-bihar-maize-and-elections

Were MSP rules relaxed to aid vote capture in the forthcoming Bihar elections?

RN Bhaskar

The three bills (now Acts) related to agriculture continue to raise a lot of dust. This column dealt with the bills last week. Yes, they are good for agriculture. But they make sense only if other things are also done first (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2020/09/two-cheers-not-three-for-the-agri-bills/).

Ironically, amid the sound and fury over the agri bills and MSP (Minimum Support Price), there are developments that appear to have escaped many. They relate to the issue of maize and may be directly connection with Bihar and the coming elections. The events leading one to such deductions appear scattered. But they all point in the same directions – elections.

First, consider media reports in July 2020 (https://www.newsclick.in/Bihar-Maize-Farmers-Blame-Government-Violating-Centre-Guidelines-Procuring-MSP) which  talked about distressed maize farmers in Bihar filing a petition before the court. They were demanding MSP for their crop. They blamed the state government for violating the guidelines of the Central Government by not procuring maize at the MSP.

talked about distressed maize farmers in Bihar filing a petition before the court. They were demanding MSP for their crop. They blamed the state government for violating the guidelines of the Central Government by not procuring maize at the MSP.

By July 2020, farmers began agitations in Bihar (https://sabrangindia.in/article/purchase-maize-under-msp-pay-differential-farmers-napm-bihar-cm). There was even a four-day long satyagraha by Kosi Nav Nirman Manch (KNNM) and other groups over the refusal of the Nitish Kumar-led NDA government in Bihar to pay the MSP for maize. The state turned a blind eye.

Nitish Kumar’s predicament could be understandable. He already had the huge surge of migrants returning home. Their remittances to their families in Bihar had thus dried up. There was the consequent rampant unemployment. The state had little funds (moreover, the state had got quite used to largesse from the central government http://www.asiaconverge.com/2020/09/india-plundered-iii-through-tax-devolution-and-transfgers/). It now appears that the state wanted the centre to pick up the tab for procurement of maize. Moreover, with elections round the corner, it looked like a game of who-blinks-first. The government reiterated its resolve not to pick up maize at the MSP. It could also be that Nitish Kumar was against the state getting involved with procurement. And rightly so.

Proceed to September 2020, when media talked about crashing maize prices (https://www.hindustantimes.com/chandigarh/maize-prices-crashed-this-time-repeat-feared-during-basmati-cotton-season/story-j3OwueZoTN3UlIRdf5F3hO.html).

And then came the agri-bills. More interestingly, there were news items in smaller publications – big media missed this altogether – that the Food Department of the government of India had asked the Food Corporation of India (FCI) and the state procurement agencies to completely avoid rejection of the stocks of the farmers in the procurement of the Kharif crops of paddy/rice and the coarse grains — jowar, bajra, maize and ragi — at the MSP (https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1659747).

It also ordered the uniform specifications for the first time for the central pool procurement of the food grains to be distributed under the public distribution system and other welfare schemes.

Obviously, Bihar’s farmers can now see good fortune coming their way.

Traditionally, procurement has been reserved only for rice and wheat – the privileged crops. Occasionally, procurement benefits have been extended to pulses. Other procurement schemes are normally announced by respective state governments for the crops that they produce.

Since maize has become a particularly important crop for Bihar, one expected the announcement of a procurement programme from the state this time. But it looks like the centre will pay the bill. After all, Nitish Kumar is also a coalition partner with the party in charge at the central government level. And Bihar is a crucial state when it comes to representation at the centre as well.

Why maize?

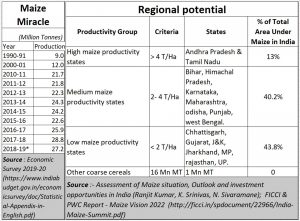

What many people do not realise is that gradually maize (or corn, or butta) has begun to gain prominence in India. During 2019-20 and 2020-21, maize production is believed to have increased substantially (the government’s agriculture ministry has a maize report only for 2012).

What many people do not realise is that gradually maize (or corn, or butta) has begun to gain prominence in India. During 2019-20 and 2020-21, maize production is believed to have increased substantially (the government’s agriculture ministry has a maize report only for 2012).

Bihar’s ranking is said to have improved to such an extent that since last year it has become the price benchmark for maize trade across India. States achieve this benchmark only when they have the production clout. Come harvest-time, say knowledgeable sources, Bihar’s roads are lined with maize kept out in the sun to dry.

It could become the principal crop for the state. As Dilip Chenoy, Director General, FICCI, points out in the paper on Maize Vision 2022 (http://ficci.in/spdocument/22966/India-Maize-Summit.pdf). “Maize is important to India as 15 million Indian farmers are engaged in Maize cultivation.”

This crop has begun generating better income for farmers while providing gainful employment. According to the FICCI-PWC report, it even has the potential for doubling farmers’ incomes. Consumption of maize has increased at a CAGR of 11% in last five years. Today, maize is a source of more than 3,500 products including specialised maize like QPM “Quality Protein Maize”.

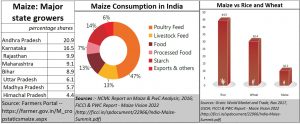

Just look at the chart above. Maize is used by a variety of industries – not to mention humans consuming it as well. They range from poultry and livestock feed, is used for making starch, and has a good export potential as well.

Poultry feed accounts for almost 47%. But the 21% share of maize as food (both plain and as processed food) has been growing rapidly. The demand for maize as food has been growing at a CAGR of 6-7% globally and at 9% in India. This also presents a huge opportunity for maize growers. In order to meet the domestic consumption needs only, India would require 45 Mn MT of maize by the year 2022, says the FICCI- PWC report.

This would be nearly double the 27 million tonnes produced in 2018-19. It would require more acreage being brought under maize or will require the existing productivity levels of maize to double from 2.5 tonnes a hectare to 5 tonnes.

There is another reason why maize is quite suitable for India – especially in regions where much water is not available. It demands less water and is known to be a ‘day neutral plant’ — it gives higher yield per hectare in a shorter period and can be grown in any season.

The multiple utilities of maize as ‘food’, ‘fodder’ as well as ‘feed’ makes it more demand-friendly and insulates it against low demand situations.

Bihar – with it large numbers of people below the poverty line (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2020/09/india-plundered-iii-through-tax-devolution-and-transfgers/) thus finds it a suitable crop for enhancing farmers’ incomes and livelihoods in India.

Globally, too, maize is the second most important cereal crop in terms of acreage and is therefore called the ‘Queen of Cereals’. Global maize production touched 1.040 million tonnes 2016-17. The US has remained the leading producer (with a 38% market share) followed closely by China (23%). India remains – relatively speaking – a marginal producer with a 2% share.

Politically relevant

Maize is extremely relevant politically as well. This is more so for Bihar because it employs huge numbers of people. And with an increasing market share within India, the MSP and procurement benefits just before elections could be a major coup for the government.

The stakes were high for this state. It is still reeling under the pressure of migrants. Many still blame the state for not welcoming them back, after they were shunted around by other states in which they worked. True, the costs of migrants returning to Bihar were daunting. But the way they were treated by their home states, including Bihar, has left scars that are quite visible (https://www.freepressjournal.in/analysis/fpj-edit-states-must-treat-migrants-with-dignity),

Thus, the MSP-procurement solution will be hugely welcomed by Bihar’s farmers. But it creates a bad precedent and could set off a dangerous trend for India.

Ideally, the government should have stayed away from procurement. It should instead have urged commodity exchanges to procure the grain. In return, central agencies could then procure through these eNAMs — through these commodity exchanges. This would have strengthened the eNAM (electronic National Agricultural Markets) and agricultural market mechanisms. It would have allowed for price discovery as well. It would have urged traders to offer competitive prices to mandis to beat the MSP offered by (government) agencies at these eNAMs. This is the way wheat and rice procurement should also go.

When the government procures grain through the FCI or the State Warehousing Corporations (SWCs), it is almost like a subsidy, with government intervention. It allows for cosy relationships between farmers and politicians. It prevents audit of the grade of crop procured and the price paid for it. Procurement through eNAMs would have solved this problem. That is the way both the FCI and the SWCs also ought to go.

The government’s intervention in grain procurement, without raising any disputes about quality, is an extremely dangerous move. It may be expedient politically. But it destroys market mechanisms. It strengthens the role of the state, and it promotes collusive and corrupt relationships.

This ought to have been avoided.

COMMENTS