https://www.freepressjournal.in/analysis/policy-watch-treatment-meted-out-to-edible-oil-reflects-the-concern-for-farmer-welfare

Edible oil and agriculture in India

RN Bhaskar

The government works hard to project itself as being farmer-friendly. It likes to maintain that it is committed to a self-reliant India (atma nirbhar Bharat). But if one looks at the government’s policies towards edible oil (and towards pulses as well — https://asiaconverge.com/2017/05/how-pulses-imports-drove-domestic-growers-to-the-ground/), these claims do not wash. The image that endures is that of a government keen on protecting trader-interests instead of farmer-interests. Clearly, there are many slips between intent and action.

Warnings ignored

In 2013, BV Mehta, executive director of the Solvent Extractors’ Association of India (SEA) warned that India was pursuing growing  dependence on edible oil imports. That, he added, was not good for either farmers, or the country. He said that the government’s perspective on oil was tragically distorted and biased against oilseed growers. A copy of his presentation can be downloaded from https://agrioutlookindia.ncaer.org/events/india-edible-oil-sector-mar.pdf

dependence on edible oil imports. That, he added, was not good for either farmers, or the country. He said that the government’s perspective on oil was tragically distorted and biased against oilseed growers. A copy of his presentation can be downloaded from https://agrioutlookindia.ncaer.org/events/india-edible-oil-sector-mar.pdf

He voiced such a warning again in November 2016 (https://asiaconverge.com/2017/09/absurd-posturing-anti-gm-lobby/) “Import of edible oil has sharply increased in last few years due to stagnant oilseed production and rising demand in the country. India’s dependence on imported oil has increased to 70% of its requirements.”

Such warnings were also echoed by the then chairman of the GCMMF (Gujarat Cooperative Milk Marketing Federation) which sells dairy products under the Amul brand, and edible oil under the Dhara brand.

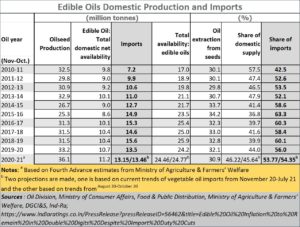

The government does not appear to have paid any heed to such warnings to date. The chart alongside shows how the government has continued to favour imports, under one pretext or another.

From importing 42% of the country’s requirement in 2010, it currently imports between 55-60% of the country’s needs. In value terms the share is likely to be higher. This is no indication of self-reliance, or farmer-protection.

Policy fiddles

The government wants farmers to look to commodity markets for  future directions. But it changes stock limits, shuts down trading in commodities and at times commodity exchanges as well. How can you expect farmers to look towards commodity exchanges for price discovery in the face of policy changes, trade bans and change in stock limits (https://asiaconverge.com/2021/12/msp-is-a-bad-idea-say-many-economists-really/)?

future directions. But it changes stock limits, shuts down trading in commodities and at times commodity exchanges as well. How can you expect farmers to look towards commodity exchanges for price discovery in the face of policy changes, trade bans and change in stock limits (https://asiaconverge.com/2021/12/msp-is-a-bad-idea-say-many-economists-really/)?

It queers the pitch for prices by constantly fiddling with import duties. Here is a quote from the government: “W.E. F. 14.06.2018, the import duty on all crude and refined edible oils was raised to 35% and 45% respectively while the import duty on Olive oil was increased to 40%. With effect from 01.01.2020, the import duty on Crude and Refined Palm Oil was revised to 37.5% and 45% respectively. With effect from 08.01.2020, import policy of Refined Palm Oil is amended from ‘free’ to ‘Restricted’ category. With effect from 27.11.2020, the import duty on crude palm oil has been revised from 37.5% to 27.5% . . . . . With effect from 06.04.2018, export of all edible oils except mustard oil was made free without quantitative ceiling; pack size etc, till further orders. Export of mustard oil is permitted in packs of up to 5 Kg with a Minimum Export Price (MEP) of USD 900 per MT.”) https://dfpd.gov.in/export-import-policy-edible-oil.htm_

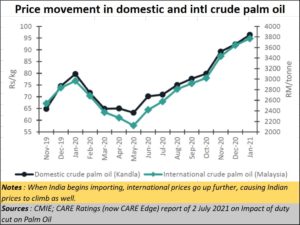

And less than 10 days ago, the government brought down the import duty on palm oil and mustard oil to just 12.5% (https://www.thehindu.com/business/Industry/govt-cuts-import-duty-on-refined-palm-oil-to-125/article38007024.ece). The reason given by the government was that it was concerned about the high prices of cooking oils. Some believe that the government instead  talked international sellers of edible oil into hiking prices (https://asiaconverge.com/2021/05/agenda-4-stop-fiddling-with-agri-and-edible-oil-prices/). The government’s talk about boosting domestic supplies and bringing down rates in the domestic retail markets only ended up pushing edible oil prices higher in both domestic and international markets.

talked international sellers of edible oil into hiking prices (https://asiaconverge.com/2021/05/agenda-4-stop-fiddling-with-agri-and-edible-oil-prices/). The government’s talk about boosting domestic supplies and bringing down rates in the domestic retail markets only ended up pushing edible oil prices higher in both domestic and international markets.

The list of grievances the trade has with government policies is long. Some of the grievances can be downloaded from 2022-01-06_Edible-oil-and-agriculture-in-India-problems. Moreover, as can be seen in the following paragraphs, the government’s arguments are specious.

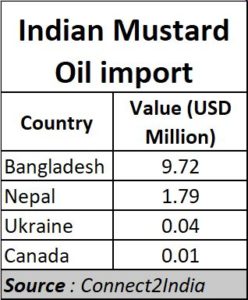

If there is a shortage of oil, and prices are rising as well, the first thing any sensible government would do is to permit blending of oils to meet the shortages in any specific oil category. Yet, strangely, in the first week of June 2021, the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) banned the blending of mustard oil – a practice that was in existence for over 30 years (https://www.business-standard.com/article/current-affairs/fssai-asks-states-to-ban-blending-of-mustard-oil-with-other-cooking-oil-121060901403_1.html). It was customary for mustard oil to be blended with other edible oils (like from palms, rice bran, etc). That helped reduce the price, and increase the availability.

The FSSAI said that this blending was unhealthy. But to do this when prices were already high, and shortages were evident, was foolhardy, if not complicit. It would appear that someone wanted India to purchase more and more of expensive mustard oil from overseas suppliers.

There is another element of absurdity in the government’s approach. It bans the use of GM seeds in India (for very good reasons). But it is willing to import edible oil from countries that are known to use GM seeds. GM seeds allow growers to increase output and reduce unit costs. Thus, Indian farmers are denied this benefit. But the government allows foreign growers to get better prices at the cost of Indian farmers.

Imports do not reduce prices

There is another factor which underscores the fallacy of government  arguments. The government believes that it can cool domestic prices by importing edible oil. But overseas suppliers are no fools. When India begins to import edible oil, international prices begin to go up. In sympathy, domestic prices also begin to climb (https://www.indiaratings.co.in/PressRelease?pressReleaseID=56462&title=Edible%20Oil%20Inflation%20to%20Remain%20in%20Double%20Digits%20Despite%20Import%20Duty%20Cuts). The result is obvious. Domestic production falters. Importers (read traders) who are close to the government and know which way policy winds will blow, make a killing. Genuine traders who want the commodity markets to grow, end up groaning. So do the farmers, who throw up their arms and decide not to grow this crop.

arguments. The government believes that it can cool domestic prices by importing edible oil. But overseas suppliers are no fools. When India begins to import edible oil, international prices begin to go up. In sympathy, domestic prices also begin to climb (https://www.indiaratings.co.in/PressRelease?pressReleaseID=56462&title=Edible%20Oil%20Inflation%20to%20Remain%20in%20Double%20Digits%20Despite%20Import%20Duty%20Cuts). The result is obvious. Domestic production falters. Importers (read traders) who are close to the government and know which way policy winds will blow, make a killing. Genuine traders who want the commodity markets to grow, end up groaning. So do the farmers, who throw up their arms and decide not to grow this crop.

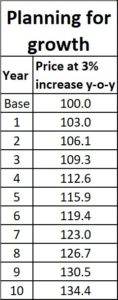

In fact, the strategy the government should have adopted even as soon as it came to power in 2014 is to promise farmers a 3-5% increase in domestic prices year on year for the next 10 years. That way in 10 years, prices would go up by only 34%. The farmer would know that oil and oilseed prices would not be allowed to fall, and would continue to grow more. Imports would decline, and both farmers and the government could be happy. This is what Kurien did with milk. A modified version of this strategy should work extremely well for edible oils.

The price assurance could be vested with NDDB which along with GCMMF sells edible oil under the Dhara brand. Both organisations are familiar with the industry. This mandate could be transferred to the most credible FPO (farmers’ producer organisation) which looks after procurement, processing, and marketing of oilseeds.

The price assurance could be vested with NDDB which along with GCMMF sells edible oil under the Dhara brand. Both organisations are familiar with the industry. This mandate could be transferred to the most credible FPO (farmers’ producer organisation) which looks after procurement, processing, and marketing of oilseeds.

Such a move would allow traders to speculate on domestic futures prices by looking at the minimum prices (MSPs) that have been assured, and make money on the price fluctuations on account of temporary shortfalls or surpluses at the retail level. That is the way to long-term economic planning. Not fiddling with policies all the time. This is one reason why many of the plans of the government have not worked. They lacked the vision and the commitment to farmer-welfare (https://wap.business-standard.com/article/economy-policy/why-did-previous-attempts-to-boost-domestic-oil-palm-production-fail-121081801195_1.html).

Potential

People often forget that India’s potential in agriculture is phenomenal. And if farmers become wealthier, it would invariably translate into a higher nationwide purchasing power, as 50% of the country’s population is linked to this sector. That in turn would drive the wheels of industry, making it more competitive. By refusing to let the farmers earn more, the government is killing the tremendous  potential offered by the agricultural sector. The only ones to benefit were those close to traders both within India and overseas.

potential offered by the agricultural sector. The only ones to benefit were those close to traders both within India and overseas.

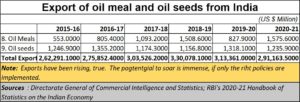

Look at how India has fared in oilseed and oil-meal exports even though the country continues to be import dependent. That should tell the government that this country’s innate competitiveness in the agricultural sector has not been allowed to grow.

Do also note that India is the third largest rapeseed-mustard producer in the world after China and Canada with 12 per cent of world’s total production. This crop accounts for nearly one-third of the oil produced in India, making it the country’s key edible oilseed crop. . India could produce more, if government policies were reliable and protective.

And yet the government lets down these very producers. Surely, India deserves better.

COMMENTS