Adani, valuations and indispensability

RN Bhaskar

At a time when the Hindenberg report is aimed at destroying the value of the shares of the Adani group, it is imperative to take a step backward, and look at valuations in a new light. The purpose of this article is not to justify present valuations, or present a new number for valuations. The purpose of this article is to highlight two principles of valuation, even as the markets look at only one principle.

I can say this, because I have been fortunate enough to write the first researched biography of Gautam Adani (Gautam Adani: Reimagining Business in India and the World, published by Penguin Random House). In that book, I have pointed out, repeatedly, that Adani’s strategy is aligning his own business interests to the interests of the nation. That in turn changes the entire valuation exercise in ways that most investors have not yet comprehended.

I can say this, because I have been fortunate enough to write the first researched biography of Gautam Adani (Gautam Adani: Reimagining Business in India and the World, published by Penguin Random House). In that book, I have pointed out, repeatedly, that Adani’s strategy is aligning his own business interests to the interests of the nation. That in turn changes the entire valuation exercise in ways that most investors have not yet comprehended.

Electricity generation is indispensable

My understanding of this principle goes back to the 1990s when I used to meet Anil Ambani – the younger brother of Mukesh Ambani of Reliance Industries. At that time, Reliance was an undivided empire. Anil he used to often explain, and I concurred with him entirely, that people must look at power generation in a different way.

“You can import steel, petrochemicals, cement, in fact, almost everything. But you cannot import electricity,” is the way he often put it. Yes, you could import energy – India is importing electricity from neighbourhood Bhutan. But it is in very limited quantities. Ditto with Bangladesh, which imports electricity from India. But that too is in very small quantities. The bulk of electricity generation for most countries is by the domestic sector.

Electricity generation, for almost every country in the world, is a crucial requirement. It is indispensable. Imports cannot replace it. Not so with food. Singapore grows very little. Almost all its food is imported. But it is a vibrant nation.

In some ways, energy security is like an army. A country cannot afford to be without its own army. Theoretically, it can ask another country to lend its armed forces. But just for a limited period of time, and in limited ways. You need your own army, and defence capabilities.

In some ways, energy security is like an army. A country cannot afford to be without its own army. Theoretically, it can ask another country to lend its armed forces. But just for a limited period of time, and in limited ways. You need your own army, and defence capabilities.

Another indispensability

Gautam Adani discovered another indispensability. Ports (and airports, a developing business for this group). Whether this was by accident, or design, is uncertain, and can be debated for hours, But Adani discovered that ports are crucial for nation building. He knew intuitively, that for a country to grow, it would need better, and many more, ports.

Today, Mundra is the fastest growing port in India. Collectively, the government-owned ports in India are no match for Adani’s ports. He has finessed the art of port building, has learnt how to make them profitable, and owns ports even in other countries – Sri Lanka, Australia, and Israel. More ports in many more countries may be expected. Expect all these ports to play significant roles in India’s growth.

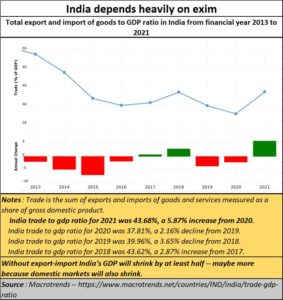

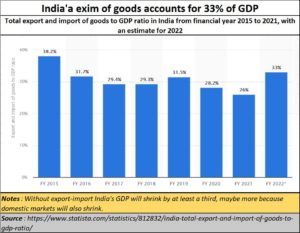

In fact, if one hones down India’s Exim trade, and focusses only on goods – services can be exported through the cloud and the internet – you still realise that almost a third of India’s economy depends sorely on export and import of goods.

Eliminate ports (and airports) and you just wipe out a third of India’s GDP. Assuming, charitably, that government-owned ports and cargo planes account for 50% of India’s export of goods, you are still left with almost 20% of India’s GDP. When a group facilitates 20% of India’s GDP, you cannot call it a fringe player.

Combine electricity and ports, and you will discover why Gautam Adani is indispensable.

Indispensability and valuation

Indispensability and valuation

That in turn raises the crucial question? How should indispensability be measured in terms of stock valuations?

The answer is that it could be anything. Conventional rules of P/E multiples, gross block or debt to equity become meaningless in such cases. It is like asking the question: How much should a child be worth to a parent? The parent does everything to save this asset, even if the amounts borrowed are several times the normal earning capacity. Of course, that does impose limits. The extent to which a rich man will spend for his ailing child will differ from the outlays of a poor parent. Yet the question is quite similar to the one that one could ask a nation – how much is a person, or his project, worth if the indispensability factor is very high?

This is where the short sellers may have got this group wrong. Adani is the largest private sector generator of electricity. He is the largest owner of ports in India, and he is setting up three additional ports in Vizhinjam in Kerala, and the Haldia and Tajpur ports in West Bengal. He has shown how it is not easy to both build a port and make it both profitable and relevant to India.

For instance, the Damra port in Odisha was originally built by the Tatas and L&T. But they could not make it profitable. So, they sold it to Gautam Adani. And — ;lo and behold – he made it profitable, and relevant to India with coal and other shipments. Add to that the logistics infrastructure – the port connectivity railways, the cargo handling and storage systems, and the methods of evacuation of the cargo – and you enable Exim in ways that were not possible earlier.

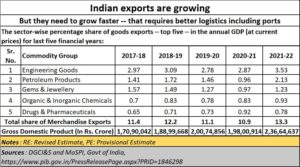

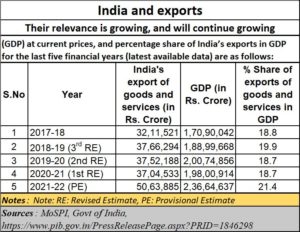

In fact, part of the credit for the growing exports from India should be given to Gautam Adani. He articulated his fundamental faith in the premise — that countries grow only when its ports and supporting logistics become better.

In fact, part of the credit for the growing exports from India should be given to Gautam Adani. He articulated his fundamental faith in the premise — that countries grow only when its ports and supporting logistics become better.

Look at it another way. None of the items India exports is large enough to achieve indispensability of the type that semiconductor and mobile telephones have achieved from China India’s pharma exports too are due to imports of crucial raw materials at cheap prices from China. Once again, China has achieved indispensability in ways that much of the world hasn’t.

India is difficult

In my book, I have tried to explain why doing business in India is extremely difficult. In my earlier book (Game India: Seven Strategic Advantages That Can Steer India to Wealth, published by Penguin Random House) I have tried to show – using an anecdote from the late Nani Palkhivala — how the government can be the biggest handicap for would-be promoters. This same is elaborated upon even more forcefully in my second book on Gautam Adani.

Succeeding in India automatically qualities it for higher price multiples than countries where setting up businesses and making money is relatively easier.

But when you combine this with indispensability, we are talking about a different aspect for valuing enterprises.

Yes, the Adani group is engaged in many other businesses – edible oil is one where he is the largest player in India. But edible oil can be imported, and Piyush Goyal has demonstrated this – quite painfully — by importing edible oil and hurting farmers (https://asiaconverge.com/2022/01/the-government-lets-down-indias-edible-oil-industry/). He almost succeeded in doing this with milk as well (https://asiaconverge.com/2019/08/indian-bureaucrats-almost-shortsold-the-milk-industry-at-fta-cpec-negotiations/), but thanks to RS Sodhi (https://asiaconverge.com/2023/01/sodhis-resignation-has-dire-warnings-for-agriculture-and-milk/) and the milk cooperatives, he could not.

The group is involved in data businesses as well. But that does not make him indispensable. He is into military equipment manufacture. Once again, they can be imported. What Adani does is produce them at a more competitive price, and make India self-sufficient to that extent.

Coal is an interesting item. Yes, it can be imported, and Gautam Adani is India’s largest coal importer. But he does that at prices no other supplier has been able to match. Yet, can he be replaced? Yes, he can where coal is concerned, though that would be extremely difficult considering that he owns the miles, operates the ships, manages the ports and is a captive consumer himself. But not with electricity and ports (including airports). That is where he has become indispensable.

That is where India, and the world, will have to use another yardstick of measurement than the one Hindenberg and other short-sellers have used.

COMMENTS