How will 2024 be for India and its economy?

By RN Bhaskar

Prognosis is judgement about how something is likely to develop in the future. It is based on symptoms that are visible today, and which may lead to consequences, unless corrective measures are taken. Broadly, India’s 2024 performance will depend on the following symptoms:

Contrary to the chest-thumping cries about becoming the third largest economy in the world, India still has a long way to go. The only sectors in which India is likely to remain the largest is in its population, and the number of poor people. Its GDP could become the third largest, but not its per capita income. Thus, you will have a government that can become rich, but with its people remaining poor. This is because even Rs.10 collected as GST (Goods and Services Tax) from each individual, fetches the government a whopping Rs.14 billion each year. The present government policies could see the middle class being shrunk (free subscription — https://open.substack.coeximm/pub/bhaskarr/p/the-shrinking-growth-of-the-middle?r=ni0hb&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web).

So, you could see GDP growing, and GST as well, but not per capita income because the base which you use to divide the GDP will keep on growing. To grow per capita income the country needs to grow at a significantly higher rate that it has been lately.

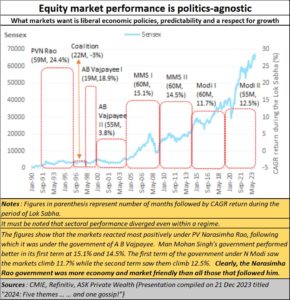

And if the past is anything to go by, the best economic growth was seen in the Narasimha Rao years, not in terms of GDP as much as in market confidence. Next came the AB Vajpayee government, followed by the Man Mohan Singh (MMS) government. During its first term, the MMS government fared better than during its second term. The Modi government may have seen more full-throated rallies than the other governments. But in terms of market growth, it has still to match up to earlier governments.

2. The markets may slump post elections

2. The markets may slump post elections

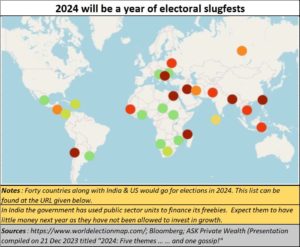

India will be facing elections in 2024. Normally, elections do not change a country’s growth trajectory, unless there is a change in government, and change in orientation. In fact, almost 40 countries in the world will witness elections. When elections take place, most serious policy changes are deferred. This will happen not just in India, but in many of the major countries worldwide. The only policies that get taken is on how to spend money to win votes. In India this is referred to as freebies, doles and revadi (free subscription — https://open.substack.com/pub/bhaskarr/p/the-indian-governments-urge-to-splurge?r=ni0hb&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web).

The trouble with doles and freebies is that they teach people to clamour for more, making them dole junkies rapidly. All talk about self-reliance (atma nirbharta) becomes plain lip service.

3. Freebies and doles

They must be paid for, preferably without showing up as fiscal deficit. This is where the government has been drawing in larger amounts of money from PSUs – even the RBI (free subscription — ). As a result, PSU profits have soared, while the private sectors profits have remained muted. After elections are over, the government will have to scrounge around for money for freebies on the one hand, and to boost productivity on the other. Given the lacklustre GDP growth, and the poor forex inflow by way of investments, government-revenues will be under a strain. Without money that could have been ploughed back into production, PSUs could be expected to perform weakly. Yet markets are booming. Something will give way.

4. Investment in manufacturing may falter

4. Investment in manufacturing may falter

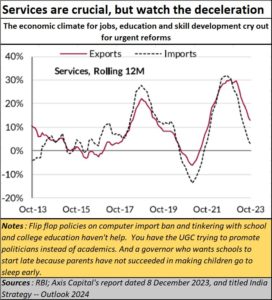

The government has put in too much of money into manufacturing which in capital intensive, and less on labour intensive sectors. The PLI schemes may have to be revamped. But then, as Raghuram Rajan, former governor of the RBI, points out, India needs to focus on the services sector (free subscription — https://bhaskarr.substack.com/p/can-india-be-the-global-growth-engine?sd=pf).

Yet as the charts show, even this sector growth is decelerating. This is because of three reasons. First, the global market which used to import India’s services (in consulting, IT, and software) is also decelerating). Second, India’s service sector lacks the education underpinning and the health services that is crucial for maintaining the momentum. India’s primary education is in a terrible condition (https://bhaskarr.substack.com/p/the-state-of-education-in-india). Ditto with higher education (https://bhaskarr.substack.com/p/the-state-of-higher-education-in?sd=pf). And India’s refusal to come to terms with these facts is worsening, not improving the situation. Its refusal to participate in the PISA rankings (https://open.substack.com/pub/bhaskarr/p/is-india-scared-of-the-pisa-truth?r=ni0hb&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web) exercise is a good example of the government’s unwillingness to accept that it has failed miserable on the human resources development front. To get the services sector regain its momentum, greater focus will be required on improving its human resources pool. Similarly, focus on law and order, especially on the safety of women, will assume greater significance, as the country will need to rope in more of its women into the workspace. The recent protest by female wresters against the government’s unwillingness to expel an alleged molester muddies these waters (https://www.reuters.com/world/india/top-indian-female-wrestler-quits-protest-over-new-president-wrestling-body-2023-12-21/). The country’s willingness to release on parole just before elections sex-offenders like Ram Rahim (https://asiaconverge.com/2017/09/should-governments-be-promoting-religion/) and Asaram is equally reprehensible. India will need to look for policies more in line with the way countries like the Vietnam deal with global players (https://open.substack.com/pub/bhaskarr/p/is-india-spooked-by-china?r=ni0hb&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcome=true).

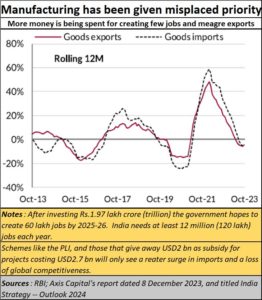

The focus on manufacturing will have to be modified. The government at the centre will have yet another task cut out for itself. It is worth pointing to the meagre job creation that has taken place. According to the government, its Production Linked Incentive (PLI) expect an outlay of Rs. 1.97 lakh crore (Rs.1.97 trillion), over a period of 5 years starting from 2021-22 to create 60 lakh (6 million) new jobs (https://pib.gov.in/Pressreleaseshare.aspx?PRID=1910034). The harsh reality is that the country needs at least 12 million additional jobs each year given the size of its population and its fertility rates.

The focus on manufacturing will have to be modified. The government at the centre will have yet another task cut out for itself. It is worth pointing to the meagre job creation that has taken place. According to the government, its Production Linked Incentive (PLI) expect an outlay of Rs. 1.97 lakh crore (Rs.1.97 trillion), over a period of 5 years starting from 2021-22 to create 60 lakh (6 million) new jobs (https://pib.gov.in/Pressreleaseshare.aspx?PRID=1910034). The harsh reality is that the country needs at least 12 million additional jobs each year given the size of its population and its fertility rates.

5. Agriculture and other labour-intensive sectors

The government will also have to rethink its plans for agriculture, leather, beef, and other labour-intensive sectors. It will have to find solutions to the country’s penchant for importing edible oil (https://asiaconverge.com/2022/01/the-government-lets-down-indias-edible-oil-industry/), pulses (https://asiaconverge.com/2017/05/how-pulses-imports-drove-domestic-growers-to-the-ground/), and banning the export of rice, wheat, onion and sugar – the last needs a separate discussion. The way a state like Uttar Pradesh pays its milk producers is also a shameful practice that keeps the country poor (https://asiaconverge.com/2022/02/the-double-engine-growth-for-uttar-pradesh-must-not-spread-over-india/).

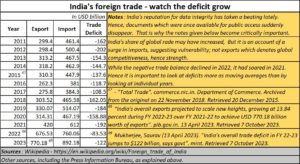

Another harsh reality is the country’s vulnerability to foreign trade. It is not a net exporter. Its negative balance of trade has been growing. It can easily reduce its import of edible oil, and agricultural produce if it follows the strategies of Verghese Kurien who made India the world’s largest milk producer without a paisa of subsidy from the government (https://asiaconverge.com/2021/11/remembering-kurien-and-how-much-the-country-owes-to-him/). It can reduce its hydrocarbon imports by focussing on rooftop solar (https://bhaskarr.substack.com/p/india-has-been-terribly-shortsighted?sd=pf) which can create jobs and address climate change and ESG concerns.

7. Labour quality and quantity

7. Labour quality and quantity

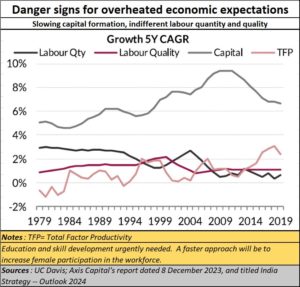

India desperately needs to find ways to improve both the number of qualified workers on the one hand and the quality of the workforce. As an AXIS Capital report puts it, “The pace of change of labour input in India is relatively predictable, though over the medium term, changes in female labour force participation as well as hours worked can raise the pace. Total Factor Productivity (TFP) growth has been improving over the past decade, and was among the highest globally in the five years preceding the pandemic. We believe this can be sustained. 2-2.5% annual TFP growth in India is driven by substantial improvements in services not just the accelerated shift to modern-trade and e-commerce, but also exports of high-value services.”

India also needs to improve the investment climate for private capital to flow into the creation of jobs.

But as said earlier, the Achilles heel will remain education, health services and security for its people, especially women.

2024 will be an interesting year, as global events play out, and India will have to realign its policies it wants to be counted among the best in the world.

Picture sourced through Bing (https://www.bing.com/images/create/can-yyoou-create-an-image-for-me-showing-a-gypsy-w/1-658aa0c641474248b72015e6fea5c985?id=PgiNxXHkZvAxEjmYLKu02g%3d%3d&view=detailv2&idpp=genimg&FORM=GCRIDP&mode=overlay)

COMMENTS