The case of the missing ecommerce regulator

By R N Bhaskar

It was in 2010 that the concept of an ecommerce regulator was hinted at, which then became a clamour. The reasons were both logical and understandable. Ever since the announcement of the National Broadband Plan 2010, followed by commercial launch of 3G mobile services in early 2011 and the launch of 4G broadband thereafter, the need for an ecommerce regulator has been a crying need.

It is foolish to talk about instant payment mechanisms, and the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) approving one method after another, without a simultaneous focus on dispute resolution relating to such transactions. It is absurd to have transactions at lightning speed, but dispute resolution at a snail’s crawl. Moreover, many disputes would not have arisen if there had been a regulator who could insist on rectification of flaws and compensation to be paid by payment gateways. There are policy issues which too would come under the regulator’s ambit.

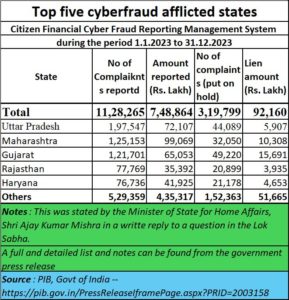

The full statement on cyber-frauds can be viewed at the government agency – the Press Information Bureau (https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=2003158).

An ecommerce regulator is needed in India because the incidence of cyber frauds has been increasing. Do remember that the numbers given out by the government do not include problems citizens have with government and quasi-government websites. The numbers in this category could be huge, if one considers the first two instances listed below.

Almost everyone was agreed on this need.

In October 2017, the then Minister of Electronics and IT, and Law, Ravi Shankar Prasad, assured everyone, that the government was alive to this need, and was working on setting up an ecommerce regulatory framework and the regulator as well (https://indianexpress.com/article/business/business-others/ravi-shankar-prasad-govt-is-working-on-regulatory-framework-for-e-commerce-companies/).

There was a great deal of expectation in those days as was highlighted in a report by Avendus titled “India goes digital” (Avendus. 2015 — https://web.archive.org/web/20150412092703/http://www.avendus.com/Files/India_goes_Digital.pdf). Everyone recognised the potential. And everyone agreed on the need to have a regulator. A U-turn … The flip

A U-turn … The flip

But in a U turn, the government in September 2023 said that there was no proposal to set up such a regulator (https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/services/retail/no-proposal-for-independent-regulator-in-proposed-e-commerce-policy-official/articleshow/103932674.cms?from=mdr)! It was time for a flip-flop.

The flop appeared to take place a year later when Reuters published a report on 7 Feb 2024 stating that the race to regulate ecommece is just beginning (https://www.thomsonreuters.com/en-us/posts/international-trade-and-supply-chain/regulating-e-commerce/). It also brought out another report (https://www.reuters.com/markets/eighty-nations-strike-deal-over-e-commerce-lack-us-backing-2024-07-26/) stating that “Around 80 countries reached agreement on Friday on rules governing global digital commerce including recognition of e-signatures and protection against online fraud, but failed to bring the United States on board”.

Three instances

Now more than ever, the need for an ecommerce regulator is being felt as an urgent requirement. If the government does not move quickly, the courts will step in, and their judgements may not be in total harmony with the objectives that the ecommerce industry may have in mind. The instances listed below deal with some of the issues involved:

- The proper functioning of ecommerce websites and payment gateways

- The mandatory requirement for receipts and refunds

- The need to regulate the way software works – especially banking software which deals with transactions. Likewise, the role of the NPCI (The National Payments Corporation of India) – its rules do not sync well with the best practices adopted by the ecommerce industry globally.

- The need to weed out misleading apps which could potentially lead to the proliferation of fake apps and cyber-scams.

- Accountability

Incident 1 – The state government of Maharashtra

Incident 1 – The state government of Maharashtra

One of the biggest violators of norms have been (some) state governments. Their websites don’t work well, and when they do, they payment gateways are flawed. At times, they don’t even have the slightest respect for the common practices that trade values immensely – of returning money when that money is not for the government to keep.

- Here is a small incident. You can read about the incident in greater detail at https://asiaconverge.com/2022/01/new-unfair-and-controversial-real-estate-tax-laws-in-maharashtra/ . Screenshots of malfunctioning website which did not give receipts can be found here — https://asiaconverge.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/2022-01-06_screenshots-transactions-amount-debited-twice.pdf

- In Dec 2021, the BMC under instructions from the govt of Maharashtra sent bills to residences North of Sion and Mahim, levying what it called the Non-Agricultural tax. On 22 March 2022, the govt of Maharashtra suspended the NA Tax notices issued to housing societies across parts of Mumbai, Thane, Navi Mumbai and Pune. The tax, introduced in March 2022, was challenged in the courts. Yet, this tax was made applicable with retrospective effect from 2006.

- Like any law-abiding citizen, I promptly decided to pay up the tax – a bit over Rs.16,000 – and logged into the identified website. I paid the money through my credit card, but the transaction failed, so the website said. So, I tried once again. This time, the transaction seemed to go through. But there was no receipt.

- Luckily, I had the sense to (a) pay through my credit card, and (b) take screenshots of each state in the transaction.

- Thus, when I checked my phone, I found I had been debited the amount twice – even for the session that had supposedly failed.

- I contacted the government department and was told (by a person I knew) that unfortunately, the government had no policy for refunds. That, at best, the government would adjust future dues. But this was a bill for 16 years. So, did that mean I would have to wait 16 years?

- So, I did the next best thing. I wrote to the credit card company, and “repudiated” the additional transaction. The rules for credit card companies are quite clear. If a customer repudiates a transaction, and if the customer has evidence to back up his claims, he must be refunded the amount erroneously debited.

- I got the second payment of Rs.16,000 refunded to me. Hence, I got back what the government refused to give to me.

- As luck would have it, the government rolled back the newly introduced NA tax because its levy was being challenged in the courts.

- Now I had a new problem. Could I get back the money I had paid? But I was told that the government does not refund such amounts.

To date I have not received my money or my receipt. This raises three questions –

- what should be the penalty the government must pay customers if its websites and payment gateways malfunction?

- What fines should a government pay when it does not issue any receipt?

- Shouldn’t there be a policy for refunds?

Had there been an ecommerce regulator, I could have approached that office. Now I – like thousands of stranded customers – am stuck. I do not want to go to court – it is too expensive and cumbersome. And I am just an individual. Thousands of similar citizens are in this situation.

This is one reason why an ecommerce regulator is critically important.

Incident II – The Mumbai traffic police.

Incident II – The Mumbai traffic police.

More details about this incident can be found at (Free subscription) https://bhaskarr.substack.com/p/is-mumbais-police-traffic-department. On 5 July 2024, I received an sms ostensibly from the police asking me to download a notice. I wasn’t sure if this was a scam and hence went to a standalone PC to download the document. I found that I had been charged with not paying my fines for seven offences, some dating back to 2022. I do not recall ever having received any intimation about such offices.

- Like any law-abiding citizen, I proceeded to pay my dues of Rs.3,600. The transaction was successful, and I took screenshots of the sms and email from the bank confirming payment through my credit card. But there was no receipt.

- I wrote to the police commissioner requesting a receipt for the amount paid. He (rightly so) forwarded my email to the Additional commissioner – traffic, who in turn forwarded it to other officers.

- A few days later I got an email from the multimedia department of the police asking me to come to the police station.

- That annoyed me and I wrote back to the additional commissioner with a copy of the email from the multimedia cell, pointing out that the email was in bad taste because

- I should not have to go to a police station for a receipt. If I paid through a website, I should get the receipt the same way.

- I am a senior citizen, and the police have instructions that such people should not be called to police stations for flimsy reasons.

- I am also disabled – my driving licence and vehicle registration also declare this. To call such a person to the police station is wrong. I got no reply.

- Some friends told me to try downloading a police app, and I began looking for it. This was confusing because there were several apps. I chose one, discovered it wasn’t what I was looking for. Then tried another. It seemed to be a right one. I fed in my vehicle details and got a list of my offences. The site said that the fines had been paid. When I asked for a receipt, I found that three of the offences issued receipts for the specified sums, but four gave receipts of the consolidated sum of Rs.3700.

- I wrote to the police asking the people there to clarify:

- If the app was genuine. My friends tell me that the app itself could be a fake one, and that I had been skimmed.

- If yes, why did the police not inform me that I could get the receipts from this app? Why was I called to the police station?

- Why did different offences have different types of receipts?

I have yet to receive a response from the police for the above queries. This raises several queries.

- Can any government or quasi department collect money through a website and ask the person to collect receipts from elsewhere?

- How does the police guide citizens to the right apps? Shouldn’t the app be synchronised with the website, so that the right receipts can be cross-checked from both the website and the app?

- Common citizens cannot argue with the police. An ecommerce regulator would have been helpful in such situations. And do bear in mind that Mumbai has one of the best police forces in the country. If this is the case with Mumbai, one shudders to consider the state with the police in many other states.

Incident III – Poor banking and payment gateway systems leading to frauds

The best example of software related bank frauds can be found in reports relating to the way the absconding Mehul Choksi and the Punjab National Bank (PNB) (https://asiaconverge.com/2018/02/pnb-why-did-the-dogs-not-bark/). Had there been an ecommerce regulator, many of the issues that the Reserve Bank of India had tried to cover up, might have got exposed. Most crucial was the fact that the banking software developer had allowed the recording of all transactions to be disabled with the use of a password. Globally, this is not allowed. Someone had cleared the banking software with the ability to disable recording of such transactions. Thus, as the earlier report points out, “The central registry had little information. Not surprisingly, the dog did not bark.”

The matter gets more complicated if you realise that NPCI (National Payments Corporation of India) has a very unusual system of clearing payments, especially when related to beneficiaries identified by the government using their Aadhaar number (https://asiaconverge.com/2018/02/how-aadhaar-and-npci-together-open-the-door-to-major-frauds-and-impersonations/). NPCI overwrites an old account number with the latest account number, thus erasing traces of the old account holder. Moreover, NPCI claims that it does not maintain logs of transactions. This is unheard of in the banking industry globally.

This, in turn can lead to huge scams, which can be stopped only by an ecommerce regulator, who can insist that the correct norms for recording transactions are adopted. Whether the scam relates to citizens or the national exchequer, the ecommerce regulator would have a major say in such matters.

The Reserve Bank of India, it appears, cannot do the jobs of regulating such transactions and practices.

So, will the government finally set up an ecommerce regulator?

The author is a senior journalist and researcher

===================

Do watch my latest podcast — a conversation with Sachin Jain of the World Gold Council, India at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0fVWIdihcbc

COMMENTS