https://www.freepressjournal.in/analysis/policy-watch-lessons-for-india-from-alibaba-about-ecommerce

Alibaba, ecommerce have lessons for India

. . . but will India be willing to learn?

RN Bhaskar — 21 January 2021

On December 24, 2020 authorities in China announced that they were investigating the Ant group which owns and manages Alibaba, co-founded by Jack Ma. Earlier, on November 3 the same year, regulators of the Shanghai Stock Exchange where Ant was planning to list, abruptly suspended its share offering (that was to open on 5 November). It cited “major issues” with the group that “may fail to meet information disclosure requirements.”

The Hong Kong’s bourse, where Ant was planning a dual listing, also followed suit and halted the proposed public offering of Alibaba. That IPO was expected raise an estimated $37 billion and boost Ant’s market value in excess of $300 billion.

The Hong Kong’s bourse, where Ant was planning a dual listing, also followed suit and halted the proposed public offering of Alibaba. That IPO was expected raise an estimated $37 billion and boost Ant’s market value in excess of $300 billion.

There are several theories explaining the sudden move of the Chinese authorities. But the purpose of this article is to focus on the lessons the incident could hold for India. Tthe subjective ‘could’ has been used because it is still not clear whether Indian authorities are willing to learn.

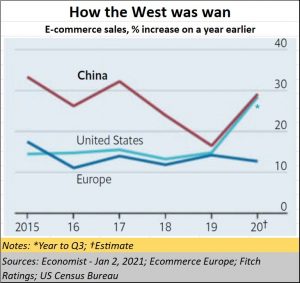

First, there is no doubt that the move was stunning. As the Economist put it, “it is in China, not the West, where the future of e-commerce is being staked out. Its market is far bigger and more creative, with tech firms blending e-commerce, social media and razzmatazz to become online-shopping emporia for 850m digital consumers.”

Second, it stunned money managers as they hoped to raise over $ 37 billion, the largest ever offering in the world being made to the investing public. Clearly, for China the money was not as important as the way it wanted ecommerce to get shaped in the future.

Third, it shook up regulators around the world. China had done something that regulators worldwide, including in India, were pussyfooting around with. It had ensured that no IT player becomes too big to fail (TBTF). In many ways, China had already begun pursuing TBTF for some years now. It had encouraged competition to the Ant Group. That proved wrong the popular belief — that China controlled Ant group. China has remained the regulator. Not the player.

There is a fourth lesson. True, China is a player in the telecom space. It owns China Telecom, China Unicorn and China Mobile. But , like most developed countries, it has not allowed telecom companies (telcos) to dabble (many countries don’t even allow shareholdings) in ecommerce companies. It understood that the surest way to kill enterprise and to stunt a vibrant industry is by letting telcos control ecommerce. Yes, the telcos will improve their profitability if they controlled ecommerce. But the country and the ecommerce ecosystem would lose terribly. Telcos would only promote the players they like. They would be wet blankets to other potential players.

It would be the same if Google were owned by a telecom company. None of the other telecom service providers would have allowed their networks to access Google search engines, and that would have stunted Google’s growth.

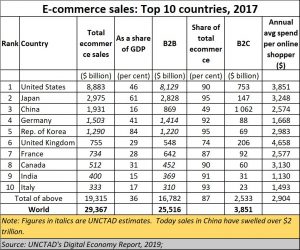

Finally, as the Economist put it, China once again confirmed that it is in China, not the US, that the frontiers of IT are being crossed. India is still bumbling around when it comes to either the vision or the regulatory setup. Today, the country’s e-tailing market is worth over $ 2 trillion.

Regulation

But what is remarkable about China is the way it has ensured that no player gets too big. It has allowed competition to emerge and protect it from being snuffed out. Thus, when the move against Ant began, ecommerce markets did not flinch. They picked up the slack, if any.

But what is remarkable about China is the way it has ensured that no player gets too big. It has allowed competition to emerge and protect it from being snuffed out. Thus, when the move against Ant began, ecommerce markets did not flinch. They picked up the slack, if any.

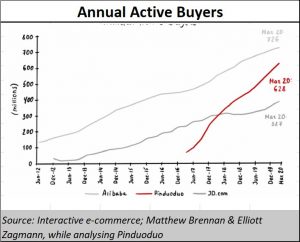

When Ant first went public in 2004, it accounted for an 85% share of market capitalisation. But China allowed several other players to emerge — Meituan, JD.com, and Pinduoduo in particular. Today, Ant’s share is around 55% today. Tthe Ant group was not allowed to smother competition.

By 2006, Ant had already moved into payment gateways through Alipay. It had over 300,000 merchants in everything from travel to gaming. By 2010, it had connections with over 200 banks in China, and had started providing payment services for online retailers outside Alibaba Group. In 2018, Ant also went into mutual insurance to address the lack of affordable healthcare for lower-wage workers. As many as 100 million users joined in the first year alone. Is IRDAI listening?

Today, Ant (and even its competitors, notably WeChat) covers a variety of services ranging from digital payments, group deals, social media, gaming, instant messaging, short-form videos, and live-streaming celebrities. Thus, while the West operated in silos –separate companies focussed on search engines, videos, social media, gaming etc — Ant brought all under one roof and created separate portals with tremendous interdependence and interplay.

Moreover, the consequences of having a large footprint can be disastrous — as recent development in the US (thanks to Trump) have shown. It is never wise to let any player become too large. Especially in areas where they have the power to shape public opinion, business rules and government policy.

What about Google?

Consider, for instance, the recent list put out by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) as on 5 January 2021 (https://www.rbi.org.in/scripts/publicationsview.aspx?id=12043). It lists out all players that have been allowed in  the financial services arena – right from ticketing companies like IRCTC to payment gateways like NPCI. You even have the likes of Ola and Amazon. But Google is missing from this list.

the financial services arena – right from ticketing companies like IRCTC to payment gateways like NPCI. You even have the likes of Ola and Amazon. But Google is missing from this list.

So, how is Google Pay allowed to operate in India? Is it an unregulated entity, the way IL&FS was? (It must be noted that, in the second week of January 2021, Google withdrew loan apps not having RBI clearance from Google store).

Or is this a slip on RBI’s part?

Or is Google piggyback riding on someone else’s licence?

Or, has Google itself become too big, and has presumed it can work its way through the system without a licence?

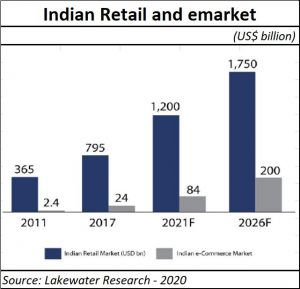

And this is happening when India’s market is still exceedingly small – both in terms of size compared to global players, and in terms of the total market dominated by physical stores (see chart). Yet watch the growth rates. They have grown from an estimated $24 billion in 2017 to $84 billion in 2021 and are expected to touch $200 billion by 2025.

India could even trounce China as its middle class grows. But for that it has to first spell out sensible regulations and its vision.

Regulatory minefield

If regulations are not put in place quickly, they will become a migraine later.

Regulatory areas are bound to get blurred as global social media networks like Facebook also move into ecash and epayments. Libra, its much-vaunted ecurrency, was given a swift burial. But fresh plans are in place. Facebook wants to reintroduce Libra in a limited format next year (https://www.ft.com/content/cfe4ca11-139a-4d4e-8a65-b3be3a0166be).

China has already introduced its own ecurrency recently. Coupled with instant messaging like WhatsApp and WeChat, the boundaries of ecurrency and the jurisdiction of central banks could become regulatory minefields. Money could be deposited from anywhere and spent anywhere as well. The situation will become a lot trickier when payment gateways like Ola or PayTM also become more aggressive and move into insurance and banking services. That could become disruptive for conventional banking. Big banks could end up becoming distribution centres, and resource centres for few high networth customers.

However, asking customers to know the colour of the money they borrow is not the solution. Most customers do not know the difference between one app and another. Most customers just want access to funds, no matter where they come from. It is the job of regulators to keep customers safe, not the job of customers to keep regulators comfortable.

That is why a discussion on regulations is urgently required, though the Indian government has been shying away from it. Regulations (Aadhaar) are currently introduced in a piecemeal manner, almost whimsically (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2020/11/double-vision-of-rbi/). The broader contours of the overarching umbrella regulations, are still missing.

Sclerotic India

India’s myopia about China could be self-defeating.

It refuses to talk to China. It has banned WeChat, even though there is so much Indian entrepreneurs could learn from it. Overnight, people who used WeChat to connect with people around the world, not just in China, have lost access to it. Even contact details are unavailable. The ban came without warning, without a cooling-off period. Caprice again.

It refuses to talk to China. It has banned WeChat, even though there is so much Indian entrepreneurs could learn from it. Overnight, people who used WeChat to connect with people around the world, not just in China, have lost access to it. Even contact details are unavailable. The ban came without warning, without a cooling-off period. Caprice again.

India has almost banned investments from China – that will slow down the pace of innovation and wealth generation. The good thing is that – despite the strictures — investments are permitted in some areas, like the metro trains or tunnel-boring machines.

Even India’s New Education Policy is myopic. It does not permit schools to teach Chinese – even though it would be the most pragmatic language to learn.

If China is an enemy, India benefits by having children who can learn Chinese and read their rules, regulations, and books. If China is a friend, the language helps foster relations faster. In any case, the largest job market will be for people who know both Indian languages and Chinese. Both sides will need such people as interpreters, facilitators, and market growers.

It is obvious that India must move quickly and encourage more people to embrace ecommerce in a variety of different ways. The UNCTAD chart (though it refers to 2017) shows that India has a long distance to go before it can run neck to neck with China. This will not happen if a proper enabling regulatory environment is not in place. Blocking access to finances is another problem. The way India’s tax laws have constantly changed – irking entrepreneurs, venture capitalists and investors – is no way to encourage market growth. Both will make India lag further behind China. The gap between both countries will grow wider.

Focus missing

India is not even bothered about the way other global players are happily working in conjunction with China to make their e-offerings that much more relevant and attractive. For instance, Walmart recently hosted its first live shopping event within TikTok – never mind President Trump’s threats. TikTok is banned in India. France  has a service called Vova which is linked to Pinduoduo’s founder. Microsoft has several joint development centres with China.

has a service called Vova which is linked to Pinduoduo’s founder. Microsoft has several joint development centres with China.

India will instead borrow technology and concepts second hand or even third hand.

Today, Pinduoduo has captured over 14% of the Chinese market, much of it at the cost of Alibaba’s share Then there is Meituan, which started out in food delivery.

There is Bytedance which owns TikTok, and its Chinese short video player Douyin.

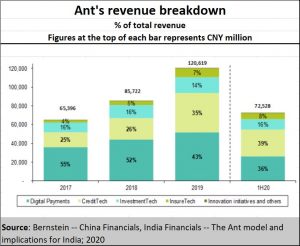

And there is Ant which straddles digital payments, credit-tech, investment-tech, insure-tech, innovation initiatives and others. But not telephones or telecommunications. As a result, employment and wealth generation in both online as well as offline services have soared.

The newcomers usher in verve to ebusiness. The government ensures – through a slew of regulations – that unfair trade practices do not drive out competitors. Similarly, both the EU and the US are working on ways to curb the dominance of Facebook and Google, and maybe others as well. Maybe Indian policymakers should watch the latest Keiser report at https://youtu.be/kj14N3GxjWA.

If India wants to be a global player, it must draw lessons from what China has done to promote ecommerce and make it the global leader. This includes zero rate strategies like the one the government is using to promote its UPI payment solution. It must realise that a greater share of a market where most players lose is not a recipe for health.

To become great, India must ensure that players remain profitable; that rules of business are not tweaked unilaterally, just to make one player profit.

But that will happen only if India truly wants to become big and a global leader.

COMMENTS