R N Bhaskar

February 3, 2014

Eventually, all ratings of domestic companies depend sorely on sovereign ratings. That was something Pradeep Shah, the founding managing director of Crisil, was never tired of reminding investors.

Translated, it means that if the sovereign rating of a country tumbles, it affects the ratings of all its companies and institutions. Effectively, poor sovereign ratings invariably find an echo in the ratings and valuations of all its companies and institutions.

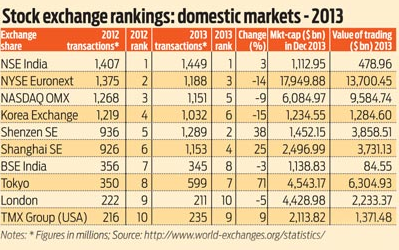

Nowhere is this as starkly visible as in the valuation and rankings of stock exchanges across the world. The data comes from the well established www.world-exchanges.org. Watch the number of transactions of electronic order book (EOB) trades (see table). That is where the National Stock Exchange (NSE) ranks #1 while the BSE Ltd ranks #7. But when it comes to market capitalisation, both NSE and BSE tumble to the bottom.

To be fair, one reason is that even though the number of transactions at both NSE and BSE were larger than most other stock exchanges, the actual value of stocks transacted is quite small. Consider how the #2 on the number-of-transactions list — NYSE Euronext – was #1 in value-of-share trading. NYSE-Euronext’s value-of-shares traded during 2013 was $13.7 trillion, compared with just $478 billion for NSE and $85 billion for BSE. But then, it must also be mentioned here that most Indian companies have remained small because the Indian government’s policies (especially those relating to licensing and labour) compelled them to remain stunted.

The second reason is that few investors respect financial and investment law-making in India. They have been witness to the manner in which trades get suspended; the way some companies are hauled over the bricks for the slightest misdemeanour, while big-time manipulators are allowed to go without even a rap on the knuckles. When fraud was detected at the National Spot Exchange (NSEL) there was hope that the kingpins would be penalised and small investors would get their money back. That hasn’t happened at yet. Significantly, no policy maker has been convicted for crimes of commission or omission in all such cases as yet.

And this does not include other forms of disregard for law-making. Tax laws with retrospective effect have already attracted much flak. Despite the criticism, India’s policy makers have not been able to resist the temptation to reinterpret laws, and introduce fresh laws to frustrate court verdicts. No wonder then, many investors have opted for the overseas arbitration route – outside the purview of Indian courts.

This lack of faith in the government is visible within the country as well. For instance, as correctly pointed out by a senior journalist, the State Bank of India (SBI), the largest government-owned bank, has a lower market cap (Rs 1.13 lakh crore) than its significantly younger private-sector counterpart, ICICI Bank (`1.21 lakh crore). Somehow, government ownership appears to contaminate valuations within India as well.

Such a view is shared by many investment analysts. For instance, Motilal Oswal’s 18th Annual Wealth Creation Study (2008-13) shows that state-owned companies have become marginalised in wealth creation.

Their share has collapsed from 51% in 2005 to just 9% in 2013. Poor governance has hit public sector units (PSUs) very hard.

It might also be worth remembering that almost 86% of bad loans belong to public sector banks. No prizes for guessing why this number is large for government-owned banks and not for private-sector banks.

Unless law makers and managers are penalised swiftly for acts of both commission and omission, the situation will not change. Unless there is confidence in the ability of lawmakers to honour assurances given to Parliament and to the people of India, Indian valuations will always go at a discount.

The willingness to revoke even Parliamentary pledges began with the Privy Purses case in 1971. Over the years, that liberty with oaths and pledges has proceeded recklessly with greater impunity.

Not surprisingly, the markets have pronounced their own verdict on the matter—by placing a discount on India stocks and financial instruments, and even on the government itself.

Click here to read the original article.

COMMENTS