https://www.freepressjournal.in/business/investments-land-is-the-smallest-part-of-the-problem

Investments: The government dangles the promise of land for global investors; but they want more important issues settled first

RN Bhaskar — 5 May 2020

The government appears to be in a rush to present a friendly face to foreign investors desirous of leaving China. It has offered them land which as some media reports put it, is “a land pool nearly double the size of Luxembourg . . . A total area of 461,589 hectares has been identified across the country for the purpose . . . . . That includes 115,131 hectares of existing industrial land in states such as Gujarat, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh” (https://www.business-standard.com/article/companies/india-offers-land-twice-luxembourg-s-size-to-companies-leaving-china-120050401614_1.html).

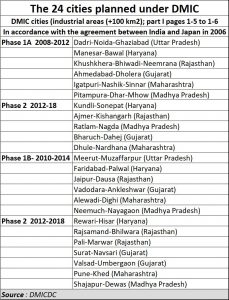

Splendid! But wait. Can someone from the government explain what happened to the 24 cities that the government of India wanted to give to Japanese investors way back in 2006?

Splendid! But wait. Can someone from the government explain what happened to the 24 cities that the government of India wanted to give to Japanese investors way back in 2006?

One of them was Dholera, in Gujarat, which was to have been spread across almost 50,000 hectares. By 2011 the state government of Gujarat was the most proactive among the six states that the DMIC (Delhi Mumbai Industrial Corridor). DMIC, was meant to cover (prime minister Narendra Modi was the chief minister of Gujarat then). The state had already acquired some 27,000 hectares of land, and work was under way for acquiring the rest (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2011/02/dmic-delhi-mumbai-corridor-will-create-new-best-class-cities/). According to Amitabh Kant, then managing director of the Dholera was meant to be larger than Shenzhen. Yet, despite the personal attention that Modi took into the project, it never really took off.

Nor did the other 23 cities. The list of cities where land was promised to Japan is given in the table alongside. The agreement was signed between Manmohan Singh and Shinzo Abe, both heads of their respective governments, in 2006. The core of the project was the Dedicated Freight Corridor (DFC) which too hasn’t taken off till today. The plan was to build planned cities on either side of this freight corridor. It was called the Delhi Mumbai Industrial Corridor project (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2011/02/dmic-delhi-mumbai-corridor-will-create-new-best-class-cities/). In 2011, the project was estimated to involve a fund outlay of not less than $120 billion and could soar even beyond this level.

The glow fades

The project did not take off for several reasons. There were conflicts between the central government and the state governments on how each city had to be set up. Land acquisition became extremely difficult. Most importantly, no state government wanted to give away land, because it was controlled by owners known to be close to politicians. Another factor was that, by the time some parcels of land were actually acquired, the processes involved in granting clearances to companies, the visa related issues, and the business guarantees required could not get resolved.

If the DMIC cities were faced with the issues listed above, the flashi8ng lights had turned from amber to red by 2014. The business environment had changed. Two of the new rules were most worrisome issues for foreign investors. First was the restraint the government had put on foreign investors from approaching international arbitration tribunals for speedy redressal of disputes (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2020/01/arbitration-and-investment-protection/). The second was the cancellation of almost all the bilateral investment treaties (BITs) the government had with investor countries. Without recourse to international arbitration, and without the guarantee of investment protection, investors were getting even more nervous

Moreover, the causes for disputes kept increasing. The most vexatious among them was the government’s increasing tendency to keeps changing the rules of business (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2020/04/india-needs-investments-china-has-the-money/).

The government had begun changing rules constantly without the consent of existing players who had already brought in their investments. It did so for the telecom sector, for e-stores and supermarkets, and even credit/debit cards. Tax laws are changed,  and imposts levied with retrospective effect.

and imposts levied with retrospective effect.

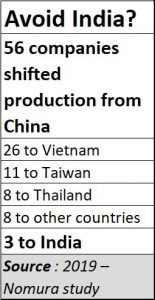

India observers were, therefore, not surprised when a Nomura study in 2019 showed that of the 56 companies that sought to move out of China as labour costs were climbing, only three opted to come to India. The others shied away, opting for other countries where the ease of doing business is far greater. India’s allure was fast fading.

What should India do?

If India wants to encourage investments, it should immediately do the following:

- Bring investment zones under the protection of Section 234 Q of the Indian constitution. Such a move protects the zone from state and central laws where labour, inspector raj and urban administration are concerned. (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2020/04/india-needs-investments-china-has-the-money/).

- Unequivocally declare that the investment zones will have access to international arbitration. Else set up courts that are treated as international centres for arbitration. Indian courts, including the Supreme Court, should not have the right to reopen international arbitration awards.

- Assure investors that retrospective tax laws, and rules of business will not be altered, failing which they will be eligible for huge reparations under bilateral investment protection treaties. Too many investors, both domestic and foreign, have burnt their fingers because of the capricious ways of governance.

- As far as it possible, convert the areas marked as coastal economic zones (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2020/04/india-needs-investments-china-has-the-money/) into such protected investment zones.

- In return the government can insist that investors will not take recourse to debt, and that debt can only be taken by the parent entities with no recourse to Indian assets. This will bring in investments and save the country from the dangers of slipping into indebtedness.

Clearly, the country with the most investible funds will be China. By excluding China from its list of investors, India will not go extremely far. It must allow investment from anywhere, provided territorial integrity, financial integrity and fair play are not fiddled with. The last rule is applicable to both India and foreign investors.

India’s economic underpinnings are extremely weak today. If it does not move along the lines described above, it could end up becoming even more desperate.

COMMENTS