https://www.freepressjournal.in/analysis/the-missing-dead-series-part-iii-can-india-be-taught-to-respect-the-dead

The entire series can be found at http://www.asiaconverge.com/2021/06/missing-dead-series/

The missing dead series – Part III

How does one ensure that deaths are recorded dutifully in India?

RN Bhaskar

Last week, he Supreme Court of India chose to reserve verdict on pleas seeking directions that ex-gratia compensation of Rs 4 lakh be paid to the families of those who have died of Covid-19. This was stated by a special vacation bench comprising Justices Ashok Bhushan and M R Shah after hearing Solicitor General Tushar Mehta and senior advocate S B Upadhyay and other lawyers for almost two hours (https://indianexpress.com/article/india/supreme-court-reserves-verdict-on-rs-4-lakh-ex-gratia-compensation-to-kin-of-covid-19-deceased-7368760/) .

The demand for compensation is understandable. A pandemic is a national calamity. When a calamity has been aggravated by government mismanagement, the demand for compensation can be justified.

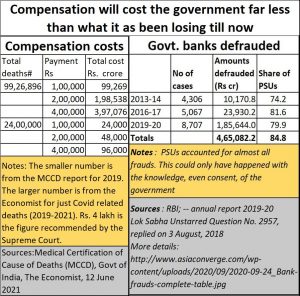

The Central government states that the compensation amount is too large. It also states that the right to decide the compensation amount vests with the legislature not the courts. Both could be fallacious arguments, because (a) the compensation amount is significantly smaller than the amounts the government has chosen to squander (see chart). And the compensation amount, when disputed, is always determined by the courts, worldwide.

The Central government states that the compensation amount is too large. It also states that the right to decide the compensation amount vests with the legislature not the courts. Both could be fallacious arguments, because (a) the compensation amount is significantly smaller than the amounts the government has chosen to squander (see chart). And the compensation amount, when disputed, is always determined by the courts, worldwide.

But then, compensation should be treated as a temporary solution. There must be a way to curb mismanagement and corruption. That is why this article suggests another way to compel people to force the government to record deaths properly.

Caveat

We are not going into the issue of whether Rs.4 lakh or Rs.10 lakh should be the compensation amount. We are showing how compensation can be used to change the way the system works.

Compensate all deaths

A good way to deal with the problem of unregistered deaths, of people who just disappear without a trace, is to allow each dead person (not just a Covid person) to get a compensation upwards of Rs.1 lakh.

There are several advantages in doing this.

First, it is reasonable to believe that except for the affluent, which comprise barely 10% of India’s population, most people don’t have access to good medicare (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2020/06/blighted-vision-for-healthcare-medical-education/). Death is therefore, usually, on account of non-availability of decent medicare which the state if required to provide. The best way to compensate the family of the person who has died is to give them a compensation.

Second, most families belonging to the middle-income or even poorer classes are often driven to bankruptcy on account of medicare costs. Thus, just like Provident Fund, which cannot be attached or mortgaged, this compensation is provided to the family only after a person dies. Suitable clauses prohibiting anyone from taking a share of this compensation amount can be inserted in the legislation to ensure that the family benefits from such compensation amount.

The most important benefit of a compensation amount being given is that it will compel families to insist that the death be recorded. There is no advantage in surreptitiously burying the body or throwing it into the river. By telling families that the dead too have a value, it teaches people and the state that the dead should be respected.

It actually cleanses a system almost overnight. This means that government officials will not have the excuse of denying compensation because of some paperwork not being made available.

Advantages

First, the total cost of compensating families of Covid deaths is not high. Even at 4 lakh, the cost is Rs.96,000 crore that too assuming a death toll of 2.4 million as computed by The Economist. The cost of compensating all registered deaths in the country (you can add 20% more as more missing dead also get registered) will be around Rs.2 lakh crore if each family is paid Rs.2 lakh. That is less than Rs.4.65 lakh crore that government owned banks lost ever since 2014.

In addition to this, the compensation helps the government clean up the leaky system it has allowed to exist.

So long as the dead person is registered on the electoral rolls, and/or has an Aadhaar card, the compensation must be paid. This compels the state to cancel such names from the electoral rolls, clean up citizenship records, and cancel the Aadhaar card.

The state will not haemmorhage on account of bogus Aadhar cards (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2020/11/aadhaar-pan-combined-through-article-139aa-threaten-banking-financial-integrity/).

It will help cancel election cards of the dead, thus preventing bogus votes from being cast.

Finally, it prevents entitlements from being claimed against the dead person’s card, because he or she still exists as a beneficiary, and thus drains the exchequer.

Together, the saving for the government will easily exceed the compensation being given out.

Government dislike

It is obvious that many legislators and bureaucrats won’t like this scheme. It compels the Census authorities to cancel names. It compels the Election Commission to sit up and take notice of the person who is dead – now officially dead because of the compensation claimed.

Politicians won’t be able to benefit from bogus Aadhaar cards and ‘expired’ election cards either.

The only other thing left to be done is to compel the Election Commission to ask the government to weed out bogus Aadhaar cards by ensuring that the Census enumerators list the Aadhaar card numbers against each legitimate voter. This way, all ‘widowed’ Aadhaar cards can be further scrutinised and cancelled. The system can be sanitised overnight.

This will require the Supreme Court to ask the Election Commission to desist from trying to permit voting from anywhere (https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/trials-to-let-you-vote-from-any-centre-soon/articleshow/80439278.cms). That would be dangerous, because it would allow bogus voters to cast votes in constituencies where the contest between two contenders is keen, and the final vote count shows up a very slim difference between the top two contestants.

Voting from anywhere can distort election immensely, and that is why the Supreme Court is willing to hear a petition against this proposal (https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/sc-to-examine-e-voting-for-people-not-in-constituency/articleshow/81100400.cms).

In fact, the Election Commission should go a step ahead and state that voting must be allowed only from places where people have a legal residence. That would deter the creation of more slums. Already, slums have been draining the country of entitlements ten time larger than what they ought to be. This is because, according to the Census, slums have an average household size of just 0.5 (preposterous) compares to over 5 on an average for the entire country (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2021/03/judiciary-3-india-forgets-the-spirit-behind-the-rule-of-law-makes-a-mockery-of-justice/). Since entitlements (rations, gas cylinders, subsidised electricity etc) are given to households, not individuals, there is a tendency to create more households per family.

By insisting that people should vote only from the place where they have a legal residence will prevent squatters. It will also reduce more ghetto like conditions which have been super spreader locations during pandemics.

India can change. But if its legislators have the vision and political will. If they don’t the courts and the Election Commission should step in and address such aberrations.

The series is concluded

COMMENTS