https://www.freepressjournal.in/analysis/opinion-rural-markets-will-decide-indias-revival

Government policies have hurt India’s rural economy

RN Bhaskar

Rural markets are in a froth. Another farm agitation appears to be brewing (https://www.firstpost.com/opinion/why-a-farmers-agitation-2-0-begins-to-roll-out-in-delhi-11097951.html). It could be messier than the first (https://asiaconverge.com/2020/12/farmer-agitations-fueled-by-corruption-politics-and-power/).

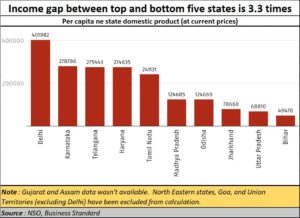

And the reasons are not hard to find. The gaps between the rich and poor states have been widening. Not surprisingly, the worst-off states are Uttar Pradesh (UP) and Bihar. As pointed out in these columns last week, UP continues to have the poorest districts in India (https://asiaconverge.com/2022/08/taxing-the-poor-and-making-them-poorer/). This is despite the sloganeering about both the chief minister of that state and the Prime Minister of India touting its double-engine growth.

And the reasons are not hard to find. The gaps between the rich and poor states have been widening. Not surprisingly, the worst-off states are Uttar Pradesh (UP) and Bihar. As pointed out in these columns last week, UP continues to have the poorest districts in India (https://asiaconverge.com/2022/08/taxing-the-poor-and-making-them-poorer/). This is despite the sloganeering about both the chief minister of that state and the Prime Minister of India touting its double-engine growth.

Death stalks the farmer

Clearly, within the state as well, the largesse poured out in terms of city development grants (or Mathura, Ayodhya and Prayagraj – the erstwhile Allahabad) have not done much to alleviate the plight of the farmers. Not surprisingly again, farmer suicides have punctured the rural development claims. There is nothing as devastating for a family when the man of the house chooses to end his life. It makes the rest of the surviving family that much more vulnerable to the exploitative forces that haunt Indian villages, especially in the Hindi belt states.

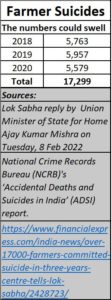

According to the statement made by Union Minister of State for Home Ajay Kumar Mishra on Tuesday, 8 Feb 2022, over 17,000 farmers had taken their lives in the three years – 2018-2020. In fact, the number could be higher, because it does not consider the 5,098 agricultural labourers who committed suicide during 2020. According to the NCRB, as many as 10,677 people ended their lives in 2020 (https://ncrb.gov.in/sites/default/files/adsi_reports_previous_year/Table%202.6%20all%20india.pdf), a number duly reported by the CNN (https://edition.cnn.com/2022/03/17/opinions/india-farmer-suicide-agriculture-reform-kaur/index.html).

According to the statement made by Union Minister of State for Home Ajay Kumar Mishra on Tuesday, 8 Feb 2022, over 17,000 farmers had taken their lives in the three years – 2018-2020. In fact, the number could be higher, because it does not consider the 5,098 agricultural labourers who committed suicide during 2020. According to the NCRB, as many as 10,677 people ended their lives in 2020 (https://ncrb.gov.in/sites/default/files/adsi_reports_previous_year/Table%202.6%20all%20india.pdf), a number duly reported by the CNN (https://edition.cnn.com/2022/03/17/opinions/india-farmer-suicide-agriculture-reform-kaur/index.html).

The numbers could climb this year, because according to media reports in August 2022. over 600 farmers farmers committed suicide in just the Marathwada region of Maharashtra between January 1, 2022, and mid-August, as per the official figures of the divisional commissioner’s office, Aurangabad (https://www.indiatimes.com/explainers/news/600-farmers-have-died-by-suicide-this-year-so-far-why-it-doesnt-stop-578047.html).

The reason often cited is that the farmers were burdened by debt. The assumption is that the farmers were reckless in their spending habits. But what is not examined carefully, is the inability of the farmers to augment their earnings. In fact, government policies have actually harmed and crippled his ability to earn, as shall be analysed a little later.

Empower farmers, don’t cripple them with subsidies

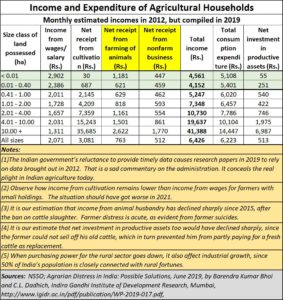

The fact is that the farmer is in distress. He is in distress because his ability to earn through cultivation has remained stunted. That in turn has compelled him to seek out incomes from two other sources – from working as a labourer, and from animal husbandry.

Those two sources of income have generated revenue streams that are two or three times the income he earns from cultivation. Then why does he not abandon cultivation? Two reasons why he does not do so. First, because of his love for the land – often ancestral. He would not like to be parted from it. And second because he stays on the same land. The government tells him that he should opt for contract farming. But that could push him from the hands of the existing middleman into the clutches of an even more powerful contractor.

A better way would be to allow the farmer to lease out his land to investors for a period of say 10 years (it takes around 3 years merely to upgrade the soil). And the rentals could be around 1.5 times annual income from crops, which could be enforced by model contracts that the government could help table. This way, the farmer continues to own the land, even stay on it, and he could continue earning from labour and livestock as well.

A better way would be to allow the farmer to lease out his land to investors for a period of say 10 years (it takes around 3 years merely to upgrade the soil). And the rentals could be around 1.5 times annual income from crops, which could be enforced by model contracts that the government could help table. This way, the farmer continues to own the land, even stay on it, and he could continue earning from labour and livestock as well.

Gradually, the farmer could also learn the role technology plays in agriculture. He could, if possible, propose to the tenant farmer a way to become a shareholder in the cultivation of land, with better agricultural practices. But the government forbids renting out of agricultural land. It prefers to keep the farmer tied to one middleman after another. It is indeed surprising that the farmer is not given a choice whether to cultivate the land himself, or to rent it out, which allows him to retain ownership of his land as well.

Livestock follies

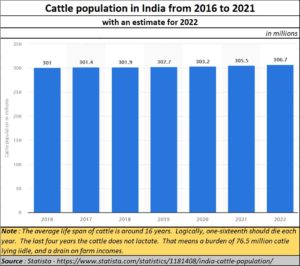

The biggest economic blunder that this government has made is to usher in the ban on cattle slaughter. While the government does have the right to decide what should be allowed and what should be prohibited, it also has the responsibility of compensating farmers for the income he has been denied from the sale of old cattle. In fact, globally, no activity can be banned suddenly, without due compensation.

The farmer used to sell his old cattle for around Rs.20,.000 per cattlehead. The ban on slaughter, meant that he would lose this money. He used to take this money, add a bit more by way of loans and purchase a young calf which could augment his income. Now he cannot do that, and taking the entire amount as a loan would cripple him financially.

Consider the following. India has around 306.7 million bovines. Cattle have a life span of around 16 years, of which he first three years are spent in growing up. Between ages 3 and 12, the cattle can lactate and give milk. Then it stops.

Consider the following. India has around 306.7 million bovines. Cattle have a life span of around 16 years, of which he first three years are spent in growing up. Between ages 3 and 12, the cattle can lactate and give milk. Then it stops.

Therefore, currently India should be having 76 million cattle that are old, which when multiplied by Rs.20,000 results in national dead investment of at least Rs.1.5 lakh crore. That is where rural wealth destruction begins. It is a bigger shock to the country than demonetisation.

What is worse, the farmer must now pay for the old cattle, which adds to his expense. Keepers of gau-shalas (cow shelters) say that the farmer can earn from the old cattle as well, by selling its urine and dung. Then why don’t the gau-shalas can keep the cattle and the income that they can get from the urine and dung, but give the farmer the Rs.20,000 he used to earn?

It is this unwillingness to compensate the farmer that has weakened rural demand. It is this unwillingness to take the old cattle away from the farmer that has burdened him with additional expenses. And the unwillingness of state governments like Uttar Pradesh to fix a minimum price (MSP) for milk so that the farmer gets at least Rs.26 per litre – the farmer in Gujarat gets over Rs.32 – has made cattle owners in that state extremely poor (https://asiaconverge.com/2021/04/little-governance-till-uttar-pradesh-is-tamed/).

Hurting rural purchasing power

There are 10 crore cattle owners, which translates into 10 crore households. Each household comprises 5 people. The government’s actions have meant that at least 50 crore people (or around 30% of India’s population) have witnessed reduced purchasing power. That, in turn, adversely affects both industry and economic growth.

But the story does not stop here. The cattle slaughter ban has affected both the meat traders and the leather industry (https://asiaconverge.com/2021/02/budget-2021-has-little-for-animal-husbandry-and-marginal-farmers/). The leather industry is employment intensive. That has hurt income generation and employment in both these sectors as well. And while buffaloes are not subjected to the cattle slaughter ban, anecdotal evidence suggests that vehicles carrying cattle meat are often waylaid, and the meat sent for forensic examination.

This is bizarre. In a country which does not have adequate forensic facilities for humans, the government has diverted these services to examining cattle meat. But the insensitivity goes further. The mean in the wagons is left in the sun, without refrigeration, and invariably becomes inedible. The transporter has lost his income and his consignment. He even gets beaten up by such vigilantes.

Effectively, the poorly thought of cattle slaughter ban has resulted in several undesirable outcomes:

- Further impoverishment of farmers

- Constricting rural purchasing power

- Farmer suicides

- Increasing poverty

- Wealth destruction

- Cascading effect on labour intensive meat and leather industries

- Economic slowdown.

If the government actually wants to improve farm welfare and revive the economy, it must begin with improving rural purchasing power first.

- Either take back the cattle slaughter ban, or compensate each farmer for unsold old cattle @ Rs.20,000 each.

- Work out a compensation scheme for meat that goes bad because of vigilante interventions.

- Work out a way for leather and meat units to continue their businesses by encouraging buffalo hide and meat (carabeef).

- Stop encouraging imports. For starters, announce a support price for oil seeds for the next two years, which will encourage farmers to grow more oilseed (https://asiaconverge.com/2022/01/the-government-lets-down-indias-edible-oil-industry/) and also wean them away from rice – a water guzzler.

- Also, do not ban futures trading in commodity markets (https://asiaconverge.com/2022/07/commodity-trading-promise-vs-performance/).

Without these, India’s economic recovery will become extremely painful. Expect farm suicides to continue to rise. And expect more farm agitations in the coming decade.

COMMENTS