https://www.freepressjournal.in/analysis/indias-deceptive-economic-performance

India’s economic performance may be worse than is being claimed

RN Bhaskar

Last week government sources were proud to showcase India’s GDP growth during the current fiscal at 13.5 %. It was left to analysts to point out that this was lower than the 16.2% forecast by the RBI (Reserve Bank of India).

Worse, when the two pandemic years of 2020 and 2021 are written off, Q1 real GDP in 2022-23 is only 3.8 per cent higher than in the equivalent quarter of 2019-20 (https://www.business-standard.com/article/opinion/india-s-q1-gdp-disappointing-numbers-122083101122_1.html). What this suggests is that either recovery is not broad-based, or that there are serious problems with India’s growth engine. It could be a combination of both.

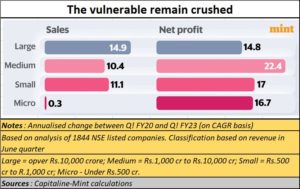

Last week, these columns talked about how the government has crippled rural purchasing power (https://asiaconverge.com/2022/08/rural-markets-will-decide-indias-revival/). The latest GDP growth rates suggest that the government has actually promoted big players. The small and medium sectors haven’t registered good growth rates. So, while large units grew at around 15% in Q1 FY23 compared to Q1 of FY20, Micro units grew only 0.3%. Government policies clearly favoured the big over the small.

Last week, these columns talked about how the government has crippled rural purchasing power (https://asiaconverge.com/2022/08/rural-markets-will-decide-indias-revival/). The latest GDP growth rates suggest that the government has actually promoted big players. The small and medium sectors haven’t registered good growth rates. So, while large units grew at around 15% in Q1 FY23 compared to Q1 of FY20, Micro units grew only 0.3%. Government policies clearly favoured the big over the small.

The more one looks at India, the more once is convinced that the government has actually hurt the poor more than it has hurt the rich (https://asiaconverge.com/2022/08/taxing-the-poor-and-making-them-poorer/). A good example of how this works is by looking at how GST functions. The seller of a good or service must pay GST at the time of drawing up an invoice. So, if a vendor sends an invoice to a large unit, which does not pay him the amounts due for three months, the vendor must not only wait for his sale proceeds, but must also pay GST upfront. This is a double whammy for small players and professionals. It clobbers the vulnerable.

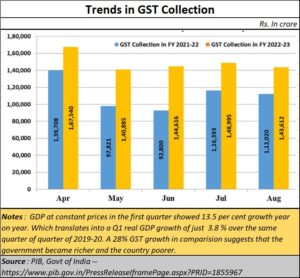

There is a second problem with GST. Revenues garnered in the month of August 2022 were Rs.143.612 crore. These were 28% higher than the GST revenues in the same month in 2021 (https://www.pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1855967).

Now, if government revenues keep climbing by 28% year on year, and the real GDP grows at only 3.8%, shouldn’t that make policy makers squirm? It means that the government is growing its own revenues, even when its people are not growing their incomes.

Now, if government revenues keep climbing by 28% year on year, and the real GDP grows at only 3.8%, shouldn’t that make policy makers squirm? It means that the government is growing its own revenues, even when its people are not growing their incomes.

Since GST is an indirect tax, which even the small poor household must pay. That hurts. The government’s increasing dependence on GST (an indirect tax) than income tax from individuals and corporates, underscores its unwillingness to make the rich pay for the government’s expenses.

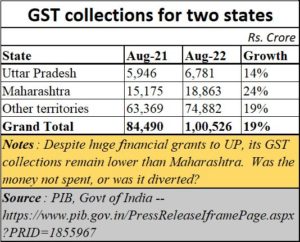

Then there are problems with the way GST revenues come in. Logically, the states which spend the most should be paying a lot of GST as well. The largest recipient of government fund transfers and ad-hoc grants – for cities, river cleaning programmes, highways, temples among others – is Uttar Pradesh (UP). One would have expected UP’s GST collections to register higher growth rates. But at 14%, it is below even the national growth rate of 19%. UP collects just one third of the revenues of Maharashtra. What happened to the dollops of cash IP got? Were the funds not spent? Or were they diverted? This does call for further study.

It also calls into question the government’s commitment to reduce the inequality between the rich and the poor (https://asiaconverge.com/2022/08/taxing-the-poor-and-making-them-poorer/).

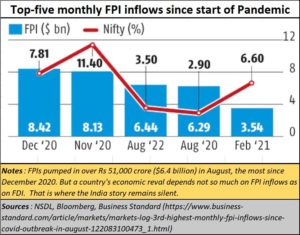

What is disturbing is the government’s refusal to admit that things are going wrong with the economy. When Member of Parliament (MP) Shashi Tharoor asked the Finance Minister in the Lok Sabha to explain the state of foreign direct investments (FDI) in April 2022, the house was informed that India continues to remain the highest receiver of the FDI, and the Indian retail investors have created the capacity to absorb the shock due to outflow of foreign funds from the country’s stock markets (https://www.moneycontrol.com/news/business/economy/india-continues-to-remain-highest-receiver-of-fdi-fm-nirmala-sitharaman-in-lok-sabha-8315161.html).

What is disturbing is the government’s refusal to admit that things are going wrong with the economy. When Member of Parliament (MP) Shashi Tharoor asked the Finance Minister in the Lok Sabha to explain the state of foreign direct investments (FDI) in April 2022, the house was informed that India continues to remain the highest receiver of the FDI, and the Indian retail investors have created the capacity to absorb the shock due to outflow of foreign funds from the country’s stock markets (https://www.moneycontrol.com/news/business/economy/india-continues-to-remain-highest-receiver-of-fdi-fm-nirmala-sitharaman-in-lok-sabha-8315161.html).

Yet when the RBI came out with the numbers this July, it became evident that India’s foreign direct investment in July declined over 50 per cent to USD 1.11 billion in July 2022 (https://www.business-standard.com/article/economy-policy/india-inc-s-foreign-investment-declines-over-50-to-1-11-billion-in-july-122083100916_1.html). Some more explanations are required.

Yet both the government and the markets have been looking exultantly and FPI flows instead. If India has to become a vibrant economy, it needs more FDI flows, not just FPI  lows. The former is long term in its commitment to India. The latter is short term, and flighty.

lows. The former is long term in its commitment to India. The latter is short term, and flighty.

But then, the way the government has treated international arbitration — the Devas case (https://www.devasfacts.com/) is the latest example — worries investors. They wonder if laws are considered sacrosanct in India.

This is despite a five-member Constitution Bench of the Supreme ruling on the manner in which international arbitration awards should be treated (https://asiaconverge.com/2020/01/arbitration-and-investment-protection/).

The flight of nigh networth individuals (HNIs) from India, the number of Indians giving up their passports and the refusal of the government to respect international awards will slow down FDI inflows (https://asiaconverge.com/2022/07/major-financial-turbulence-ahead-inr-may-weaken-further/).

There is a crisis of confidence in the government’s approach to disputes and the manner in which its agencies pick up targets. Consider the way the Competition Commission of India (CCI) has been selectively targeting Amazon, Flipkart and now Zee-Sony. The choice of targets appears capricious, without a clear approach to target companies that affect common folk. Consider, for instance, the manner in which it has not hauled up ride-sharing apps like Ola and Uber for not leaving customers with confirmation of the fare at which they have booked their rides. They used to do so earlier, but have discontinued this practice (https://twitter.com/rnbhaskar1/status/1565191370477895680?s=20&t=JNDQS6JicTWdCUYCaShr_Q).

India needs to become friendlier to long-term capital. That is the only way the country can increase the purchasing power of the bulk of its population. No wonder then, Moody’s has sharply cut India’s GDP growth forecast for 2022 to 7.7 per cent for 2022 and to 5.2 per cent from 5.4 per cent in 2023 (https://www.msn.com/en-in/money/markets/sharp-cut-in-india-s-economic-growth-moody-s-cuts-gdp-growth-forecast-to-77-for-2022-here-s-what-will-hurt/ar-AA11laud). Moreover, when it comes to countries in emerging markets, India has a (lower) Baa3 stable rating compared to Brazil (Ba2 stable), Indonesia (Baa2 stable), Mexico (Baa2 stable) and South Africa (Ba2 stable). It must be said, however, that Moody’s believes that India could revive sharply in the coming months.

Finally, as market analyst Shyam Ponappa points out (https://organizing-india.blogspot.com/2019/04/delayed-cash-flows-and-npas.html) one of the biggest problems plaguing India businesses is delayed payments by the government. “Central and state government payments are often delayed, apparently even more than in the private sector. Even government payments related to high priority IT systems, for instance, are notoriously delayed. Major IT companies complain of losing money on large projects for this reason. Nasscom estimated a couple of years ago that government dues to the IT industry could be more than Rs 5,000 crore.”

India has the potential and the promise. But it needs good governance. It needs a government willing to let farmers earn more. It needs sagacious planners not to cripple even healthy industries like milk with subsidies.

It must protect small entrepreneurs who form the backbone of India’s mass-scale wealth generation. These include both farmers and micro enterprises. It should introduce a tax structure that does not make the weak weaker.

But most of all, it needs better flow of information, and the willingness to discuss numbers across the table with its citizens. Today, the information flow is being choked. And that slows down the wheels of commerce, which sorely depends on economic information.

India’s rise to becoming a global power will depend on these factors.

COMMENTS