Is India heading towards a sugar and oil import crisis?

By RN Bhaskar

The Bing-generated image above depicts locusts ravaging a sugarcane plantation, Mercifully, that has not happened in India so far. Instead you have proverbial locusts, which see agriculture as a means to enrichment and power at the expense of the entire country. They seem to be growing in number. Consequently, policies relating to sugar and ethanol are being warped.

The biggest victim of these proverbial locusts appears to be Maharashtra (https://asiaconverge.com/2023/03/maharashtra-has-a-fatal-obsession-for-sugarcane/), though other states have their own rapacious players. Irrespective of which state allows which pests to flourish, the eventual result is immense risk to farmers, industry and even the Indian economy. Sugar is not as sweet anymore.

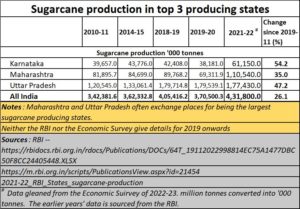

Global trade data shows that while Brazil is the top global exporter of sugar, India has occasionally been the largest producer. But that situation could be ending, if the government does not wake up and remedy its sugar-related policies. It won’t be long before the country slips even further in global rankings.

To better understand this, it is imperative to first focus on the way the three largest sugar producing states in India have grown.

Uttar Pradesh is the largest sugarcane producer. But Maharashtra hopes to become No.1. Unfortunately, Maharashtra has little water, unlike Uttar Pradesh, and even less than Karnataka. But the people who control the dynamics of sugarcane production in Maharashtra and Karnataka do so through cooperatives. These cooperatives significantly influence the politics and policies for the states. Uttar Pradesh has few cooperatives. The state does not like them. It has private sugar mills instead, each given a command area from where they can pick up the sugarcane.

The sugar barons working through cooperatives enjoy one advantage. They are headed by people very active in state and regional politics. They do not belong to a single political party, because business interests cut across party lines. It is the presence of these people which makes their cooperatives quite different from the type promoted by Verghese Kurien, the man behind Operation Milk Flood. Kurien’s model demanded that the entire cooperative be owned by farmers.

As stated above, the key persons in the Maharashtra and Karnataka cooperatives are usually headed by people who play an active role in state politics. They treat the cooperatives as vote banks. As a result, while farmers in cooperatives run upon the Verghese Kurien model get a major part of the revenues, in Maharashtra and Karnataka, it is the politically active heads who get enriched. . In the case of milk, in the Kurien modelled cooperatives, now promoted by NDDB, the farmers get 80% (sometimes even more) of the market price of milk (https://asiaconverge.com/2020/02/verghese-kuriens-milk-model-curdled/). In Maharashtra and Karnataka, the farmers in their respective cooperatives get almost half the revenue share.

In these states, the sugar factories and milk processing and marketing plants are not owned by the farmers. Nor are the distilleries, which are run as separate companies. The farmers get no share of the money that is generated by these lucrative businesses. Invariably, these cooperatives claim that they have made losses. But if the Kurien-modelled cooperative can be run profitably, someone needs to investigate why and how the other cooperatives make losses.

These is another interesting way in which Maharashtra and Karnataka function. Politicians are wont to offer higher sugarcane prices to farmers, often in excess of what the sugar companies can afford. So, the state government gives a subsidy to the sugar units, and they manage to cope with the higher prices that farmers may be given. In fact, even cooperative banks have often managed to get their seed capital provided by the government, which has not insisted on a seat on these banks’ boards.

In the case of milk, while the Kurien patterned cooperatives finance themselves – profitably — without any subsidy from the government, in Karnataka and Maharashtra, subsidies are the norm. That, in turn promotes the inefficient, and grievously hurts the efficient. The biggest beneficiaries are the politically-connected heads of cooperatives and affiliated activities. The losers are invariably the farmers and even the country.

Irrigation games in Maharashtra and Karnataka

Irrigation games in Maharashtra and Karnataka

In Uttar Pradesh too, where there are almost no cooperatives, politicians announce the prices for sugarcane purchase, often in excess of what the sugar mills can afford. So, sugar mill owners have to play along with the politicians to persuade them to fix a price that would help politicians make some money, and the farmers as well. But the farmers get a raw deal, which can be worse than the lot of farmers in Maharashtra or Karnataka. Do remember that the lot of farmers in the two states is worse than that of farmers in the Kurien-modelled cooperatives.

In fact, Uttar Pradesh is the most exploitative state both for farmers (https://asiaconverge.com/2021/08/poverty-in-uttar-pradesh-and-bihar-is-not-accidental/) and even women (https://asiaconverge.com/2021/07/hindi-belt-ii-crimes-against-children-and-against-humanity/).

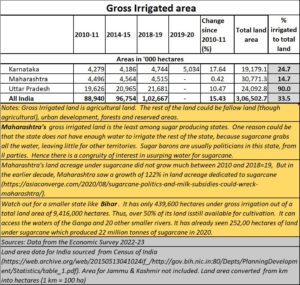

The rapaciousness of the sugarcane lobby can be understood when one looks at gross irrigated land as a percentage of the total land in the top three sugar producing states. Watch the way the sugarcane lobby has ensured that the entire state does not get properly irrigated in Maharashtra and Karnataka. The water is largely used by the sugarcane industry.

Sugarcane is a water guzzling crop. So, in a state that does not have enough water, the best way to ensure money from sugarcane is by ensuring that water does not reach the rest of the state. In Maharashtra, barely 15% of the land is irrigated. In Karnataka, the figure is higher at 25% — 2019 figures because the latest figures are not consistently available for later years. But neither state has achieved the 90% figure of Uttar Pradesh.

Worse, the state governments of both Maharashtra and Karnataka have been generously permitting sugarcane growers to increase acreage for this crop. In Maharashtra for instance, between 2000-011 and 2010-11, the government allowed for a 52% increase in sugarcane acreage from 687,000 thousand hectares to 1,041,000 hectares. This was even after knowing that the state did not have enough water. But the sugarcane lobby was influential and savvy enough to ensure that the total area under irrigation did not increase.

If India has to grow more sugarcane it must seriously begin looking for options beyond these states. There is no other alternative.

That is one way it will be able to reduce its import of oil for vehicles. By allowing the blending of fuel with ethanol, it can reduce its dependence on imported fuel.

Uttar Pradesh is almost fully covered with some kind of crop or the other (90% of its land is already irrigated).

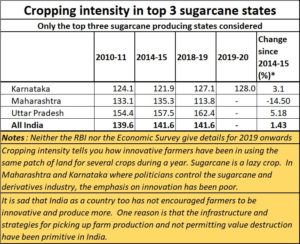

Maharashtra and Karnataka have no additional water. To improve the lot of their farmers they must teach farmers to go in tor more crop intensive farming or crop rotation. Look how poor crop rotation is in these two states compared with Uttar Pradesh. The latter enjoyed a crop intensity (2018-19 figures) of 162% while Maharashtra and Karnataka registered a lower 114% and 127% respectively. The average India crop intensity stands at 142%, lower than that for Uttar Pradesh.

One of the few hopes for augmenting sugarcane production, and to reduce the dependence on both Maharashtra and Karnataka is by urging Odisha and Bihar to take up this crop more aggressively than they have till now.

Strategic Bihar

Bihar used to have a vibrant sugar industry, till politics messed up with both the farmers and industry, and the casualty was this crop. But it has begun reviving. With the right encouragement from the government, this state could actually change the fortunes of its people.

Bihar is interesting because only 47% (43.86 lakh hectares) of Bihar’s 94.16 lakh hectares of land is irrigated. It has already begun focusing on sugarcane and 2.52 lakh hectares are under sugarcane cultivation. There is enough land for more sugarcane cultivation.

People often ask – why should India produce more sugar?

There are three reasons for this.

First, that is one way we could minimise the chances of the central government banning exports of sugar. Sugar and its derivatives could become key export earners if the right policies are put into place. The central government often tries to wash its hands off this subject by claiming that agriculture is a state subject. But it likes to conceal the fact that it has the power to decide which crops should attract tax-free benefits, and which crops shouldn’t. Consider how it imposed income tax rules on farmers who have more than 100 cows. Milk belongs to the agricultural sector. If the government can bring in this industry under the tax purview beyond a certain stage, it can easily do similar things to encourage or curtail sugarcane production.

Second, India will need lots of sugarcane if it wants to reduce its oil import bills. That in turn will help India reduce its trade deficit (India’s imports have consistently been higher than its exports — free subscription — https://bhaskarr.substack.com/p/india-prognosis-2024?r=ni0hb&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web). The best way it can do this is by boosting the production of ethanol for lending with fuel used to drive vehicles. Remember, ethanol blending helped India save Rs.24,300 crore last year (https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/renewables/ethanol-blending-program-saved-rs-24300-crore-foreign-exchange-in-2022-23-hardeep-puri/articleshow/106536867.cms) Ethanol is also used for making acetic acid, the building block for the pharma industry.

Ethanol roadmap

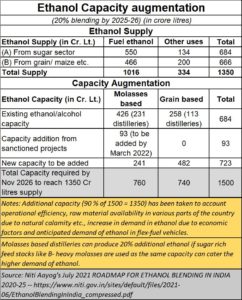

In its 2021 report (https://www.niti.gov.in/sites/default/files/2021-06/EthanolBlendingInIndia_compressed.pdf), Niti Aayog prepared a roadmap for boosting ethanol production. Unfortunately, many policymakers do not read such reports, or work towards making India more self-reliant. It had then pointed out that as against the total existing ethanol production of 684 crore litres per annum, India would need an additional 723 crore litres of ethanol by 2025-26. And while grain can also be used for making ethanol, the molasses (read sugarcane) route is more desirable because of its output and the availability of sugarcane.

That, said Niti Aayog in this report, will allow the country to achieve a desired total capacity of 1,350 crore litres by Nov 2026.

The deadline is just two and a half years away. It will take at least a year to get the right policies in place and to persuade the farmers and the state to get more land under sugarcane cultivation. But the government, as always, is a bit too late.

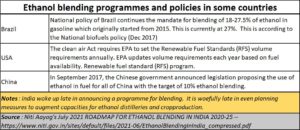

Ironically, this has been the case despite other countries setting up ethanol production facilities as early as 2017. India like to boast that it will be a global leader. But in terms of finalizing the right policies for strengthening the country’s domestic supplies, it has invariably been a laggard.

In three of the several countries surveyed by Niti Aayog, Brazil (the world’s largest sugar producer) had its ethanol policy in place by December 2017. The US did this through its environmental laws, which saw merit in promoting corn and sugarcane-based ethanol.

China, India’s bugbear (https://open.substack.com/pub/bhaskarr/p/is-india-spooked-by-china?r=ni0hb&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcome=true), finalised it policies even before Brazil, in September 2017.

India isn’t ready even today.

It is quite possible that both Karnataka and Maharashtra will lobby hard against the promotion of an omnibus sugar policy, or for promoting sugarcane growth in sugarcane production in Bihar and Odisha or for curbing production in their own states. But the centre will have to decide whether these two states are more important than the country.

Without ethanol, India’s balance of trade will get worse. Its vehicle manufacturing plans will also be hit because of uncertainty.

Will the policymakers wake up?

COMMENTS