https://www.freepressjournal.in/analysis/stanchart-seeks-to-control-the-destiny-of-indian-banks-and-profit-foreign-firms-says-rn-bhaskar-2

Stanchart seeks to control the destiny of Indian banks and profit foreign firms

RN Bhaskar

To understand how Standard Chartered Bank (SCB or Stanchart) works in India, one has only to go to the way it acted in the matter relating to the dues of the Essar group.

It had lent huge sums to Essar, mostly as unsecured loans. When the liquation of Essar’s assets began, Stanchart did everything in its power to get clubbed along with secured creditors, thus laying claim on secured assets where were to go to Indian banks.

Sadly, even NCLAT (National Company Law Appellate Tribunal) decided that unsecured creditors could be clubbed with secured creditors. This was unheard of — in banking and debt management. NCLAT was “dissatisfied of the pay-out ratios, took the view that operational creditors stood on an equal footing as financial creditors and their claims had to  be considered at par with those of financial creditors. NCLAT’s judgment given in Essar Steel matter had the effect of taking insolvency resolution processes under the IBC completely off track” (https://insolvencyandbankruptcy.in/supreme-court-ruling-on-essar-steel-under-ibc/).

be considered at par with those of financial creditors. NCLAT’s judgment given in Essar Steel matter had the effect of taking insolvency resolution processes under the IBC completely off track” (https://insolvencyandbankruptcy.in/supreme-court-ruling-on-essar-steel-under-ibc/).

Other Indian banks protested, notably ICICI and SBI. Finally, the dispute landed in the Supreme Court. It held that “the principle of “equality” could not be interpreted to mean that all creditors (irrespective of their security interest or their status as operational or financial creditor) should get equal recovery under a resolution plan. (https://www.mondaq.com/india/insolvencybankruptcy/1058270/case-note-judgement-of-the-supreme-court-in-the-essar-steel-case).

Eventually, Stanchart was compelled to write off at least “$850 million lent to the Essar Group, as part of the repayment plan” (https://www.ibtimes.co.in/essar-repays-loans-icici-bank-axis-bank-standard-chartered-bank-700863).

Like in the Essar case, Stanchart was trying to turn all rules relating to banking, and adjudication, on its head.

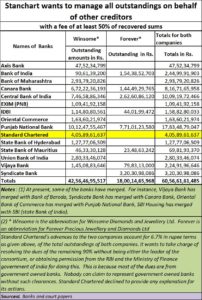

This time, a similar situation appears to be taking place in its stand vis-à-vis dues owed to it by Winsome and Forever (acronyms for Winsome Diamonds and Jewellery Ltd., and Forever Precious Jewellery and Diamonds Ltd). Both companies together owe Stanchart around Rs.405 crore. But that is just around 6.7% of the total amounts outstanding.

It wanted to be the tail that could wag the dog.

But there is much more than power play here. At stake are rules relating to banking, Indian sovereignty, and the sanctity of Indian laws. This is because most of the money is owned to government-owned Indian banks, which means Indian taxpayers’ money.

To understand this, one has to go back to another article penned by this author (https://www.freepressjournal.in/analysis/jatin-mehta-files-a-usd-5-billion-suit-against-de-beers-stanchart-and-kroll). It was about a civil suit for $ 5 billion that Jatin Mehta, the promoter of both Winsome and Forever, had filed against De Beers , Stanchart and Kroll.

According to the submissions (In Para 87) before the court in Surat (where almost all the diamond cutting and polishing takes place in India), the lending banks jointly decided that on the basis “of quotes received from 3 audit firms namely Haribhakti & Co., Price Waterhouse Coopers and Ernst & Young (EY), work would be shortly awarded to the selected firm.” Kroll was not recommended. But Stanchart “unilaterally decided to induct Kroll.”

Stanchart appears to have got stung by this civil suit filed in Surat. Shortly thereafter, Stanchart decided to file a case against Jatin Mehta and his family in the UK. When this author wanted to get a copy of the submissions that Stanchart made before a UK court, the request was turned down on 31 July 2022. The bank responded with a statement that “As the matter is sub-judice, we prefer to refrain from making any comments. The Bank will suitably respond before the Court.”

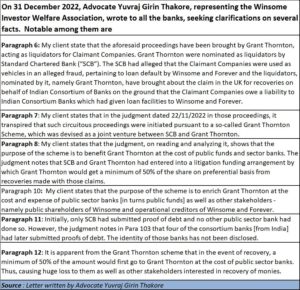

But the court documents reached this author through letters — that Advocate Yuvraj Girin Thakore, representing the Winsome Investor Welfare Association, wrote to all the banks on 31 December 2022. The letters sought clarification from the banks on several facts (for a full copy of the excerpts from the UK court papers, please click 2023-01-26_Excerpts from the UK judgment dated 22 November 2022,)

But the court documents reached this author through letters — that Advocate Yuvraj Girin Thakore, representing the Winsome Investor Welfare Association, wrote to all the banks on 31 December 2022. The letters sought clarification from the banks on several facts (for a full copy of the excerpts from the UK court papers, please click 2023-01-26_Excerpts from the UK judgment dated 22 November 2022,)

The letter to the banks highlighted the manner in which Stanchart and the accounting firm Grant Thornton (GT) had entered into a litigation funding arrangement. This arrangement would allow GT to recover the money owned to banks by Winsome and Forever. In return, GT would get a minimum of 50% of the share on preferential basis from recoveries made with those claims.

In other words, Indian banks would lose 50% of the money that would be recovered, and would have to share only the remaining 50%. This was even worse than the bounty hunters one read about in the US wild west.

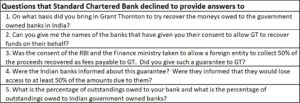

That raised several questions that we asked Stanchart.

We wanted to know the following:

- On what basis did Stanchart bring in GT to try recover the moneys owed to the government-owned banks in India? Its name was not shortlisted by the Committee of Creditors, according to the suit filed in Surat.

- Could Stanchart provide the names of the Indian banks that have given their consent to allow GT to recover funds on their behalf?

- Could Stanchart explain if the consent of the RBI and the Finance ministry had been taken to allow a foreign entity to collect 50% of the proceeds recovered – which were to go to government-owned Indian banks — as fees payable to GT? We also wanted to know if Stanchart had given such a guarantee to GT.

- Were the Indian banks informed about this guarantee that Stanchart appeared to have given to GT? Were they informed that they would lose access to at least 50% of the amounts due to them? Surely government-owned banks could not unilaterally declare that bounty fees of 50% of the proceeds could be given away as reward or fees to a foreign entity.

In the Essar case, Stanchart did have some support from the (highly irregular) judgement of NCLAT. Did it have any legal document before making such a statement before the UK courts? Would this not “enrich Grant Thornton at the cost and expense of public sector banks”?

In the Essar case, Stanchart did have some support from the (highly irregular) judgement of NCLAT. Did it have any legal document before making such a statement before the UK courts? Would this not “enrich Grant Thornton at the cost and expense of public sector banks”?

Stanchart sent in a terse one-line reply. It stated on 16 January 2023: “We decline to comment.”

We do not know if the government-owned Indian banks have challenged this submission to a UK court. As of now, we have no knowledge of any suit being filed in Indian courts, or even in the UK courts. We have asked the banks to clarify, and are waiting for their response.

A copy of the letter to Stanchart, seeking clarifications, was marked to both the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) and the Ministry of Finance. We have heard nothing from them either. The matter is serious because a foreign bank has sought to profit itself and its associates by putting the entire burden on Indian taxpayers.

It may be mentioned here that the courts in the UAE have already confirmed that Winsome and Forever were defrauded by other parties, which in turn compelled even the CBI to drop charges against Indian bankers who had sanctioned the loans in the first place. When an attempt was made to recover the funds through NCLT, Stanchart objected and scuttled the move.

For a country that was totally against Indian issues being debated in foreign courts (it scrapped most of its bilateral investment treaties with many countries — https://asiaconverge.com/2019/05/effective-dispute-resolution-needed-for-increase-in-fd/) its silence on the submissions before a UK court is baffling.

With the RBI and the Finance Ministry throw light on such developments?

COMMENTS