Air-India — a story of corruption, mismanagement and greed

If one wants to get an inkling of the mess at Air India — the merged entity of the erstwhile Indian Airlines and Air-India — do not go to the annual reports. Clever accounting fiddles like sale and leaseback of six A310 aircraft, inflated rental incomes, deferred tax benefits, and capitalisation of maintenance expenditure, to name a few, make financial transparency a laughable matter.

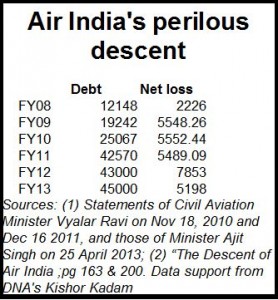

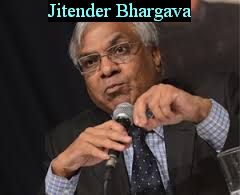

But the statements of the Union ministers of civil aviation in 2010 and 2011 show that the situation at Air India is critical. So do the revelations by Jitender Bhargava, former executive director, Air India, in his recently released book ‘The Descent of Air India’ and at his talk at the book-launch event organised by Moneylife Foundation. Both tell of how the airline today is awash in debt (see table) and needs an urgent injection of Rs 30,000 crore just to stay afloat.

But the statements of the Union ministers of civil aviation in 2010 and 2011 show that the situation at Air India is critical. So do the revelations by Jitender Bhargava, former executive director, Air India, in his recently released book ‘The Descent of Air India’ and at his talk at the book-launch event organised by Moneylife Foundation. Both tell of how the airline today is awash in debt (see table) and needs an urgent injection of Rs 30,000 crore just to stay afloat.

While several acts of commission and omission can be attributed to the decline of Air India, two factors contributed the most.

First was the unwarranted purchase of 68 aircraft, without even a business plan. Even the comptroller and auditor general (CAG), in a damning report on Air India tabled in Parliament on September 8, 2011, criticised Air India’s decision to acquire 68 Boeing aircraft in 2005, stating that it imposed an “undue long-term financial burden on the carrier”. The CAG report points out how, on March 16, 2006, the aviation ministry made a noting for the merger of Air India and Indian Airlines. Within six days, a presentation was readied for the prime minister. Strangely, the presentation itself disappeared without a trace.

But prior to this merger, the recommended increase of just 10 aircraft – which was economically viable – swelled into an cripplingly unviable order for 68 for Air India (23 B777s, 27 B787s and 18 B737-800s) and 43 for Indian Airlines (19 A319s, 4 A320s and 20 A321s). This alone added at least Rs 40,000 crore to Air India’s debt burden.

But prior to this merger, the recommended increase of just 10 aircraft – which was economically viable – swelled into an cripplingly unviable order for 68 for Air India (23 B777s, 27 B787s and 18 B737-800s) and 43 for Indian Airlines (19 A319s, 4 A320s and 20 A321s). This alone added at least Rs 40,000 crore to Air India’s debt burden.

Second was the willingness of the government to allow foreign – and Indian private – airlines, through bilateral agreements, more seats on flights to and from India. This left Air India at a massive disadvantage. As a result, the total number of seats to/from India swelled from 4.31 lakh per week in January 2004 to 16.49 lakh by March 2010. This year, the number is expected to cross the one million mark. The biggest beneficiary could be Etihad Airlines – through its pact with Jet Airways – a deal that is now being scrutinised by the Supreme Court.

Both factors appear to be nothing short of a sellout of the company, and the nation. In his book, Bhargava states quite candidly, “Air India witnessed its worst phase of political interference during the Praful Patel-V Thulasidas tenure – Patel was the Union minister, civil aviation, and Thulasidas was chairman and managing director of Air India – during which acquisition or leasing of aircraft, purchase of merchandise, appointments, giving out free air tickets and upgrades, and on promotions, transfers, and postings of employees were taken without any thought for the airline’s future.”

The brazenness with which it was done is evident from the manner in which it was propelled. It was first mooted in October 2004, and V Subramanian, then additional secretary and financial advisor, ministry of civil aviation, and also director on the board of Air India, asked chairman Thulasidas for the business plan for justifying such a large capital expenditure. The chairman is quoted as having stated, “The minister wants it.” But Subramanian insisted that a business plan was a pre-requisite to such a clearance. Surprisingly, N Vaghul, an independent director on the board, stayed “silent”. Raghu Mohan, another director, “absented himself”. The decision to purchase the aircraft was deferred – but only for a while. However, Subramanian, who left the meeting to catch a flight discovered enroute that he had been shunted out from the ministry of civil aviation – hence, stripped of his directorship of Air India – to the ministry of rural development. It goes to show that when the government wants to act, it does so with remarkable alacrity. Was this an act of collusion between the ministries of civil aviation and rural development? Can a secretary of the government be transferred from one ministry to another without the consent of the Department of Personnel & Training (DoPT) which is headed by the Prime Minister of the country?

There are other equally worrisome questions. Why has the CVC kept silent? Why did the prime minister’s office give Praful Patel a clean chit in one case even while many of the allegations continue to be investigated by the CBI? Why has no action been taken on the basis of the CAG report? And how was an indictment of an employee by Air India’s Vigilance Department suddenly cancelled – thought the CBI subsequently revived the case in 2012?

The government has apparently been collusive. And eventually, the entire mess may have to be addressed by none less than the Supreme Court. That is what happens when responsible management of public funds is ignored by both the executive and the legislature, leaving policy redressal to the apex court.

COMMENTS