Smart cities and affordable housing

http://www.dnaindia.com/money/report-policy-watch-planning-for-smart-cities-2039898

Bayer India inaugurated – in January 2011 — its first 930 cubic metre emissions-neutral office building in Asia as part of its group-wide sustainability programme. Located in Greater Noida, near New Delhi, it draws 100% of its electricity from a photovoltaic plant, and requires approximately 70% less power than comparable buildings in the region.

Today, it is the only LEED Platinum status Eco Commercial building (ECB) in India, because it is an environmentally sustainable building, meeting an impressive 64 out of 69 parameters laid down by LEED. By 2013, it produced more electricity (68,748 kWh) than what it consumed (67,258 kWh), leaving it with a surplus of 1,490 kWh for the year.

Managing costs

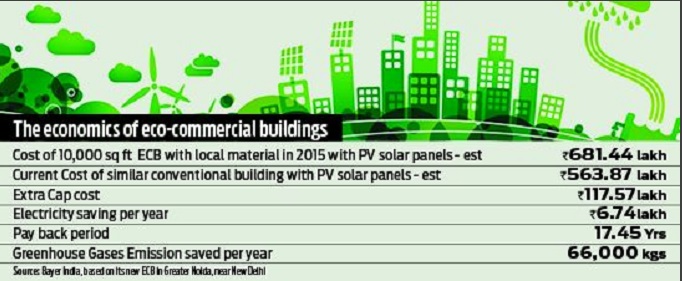

True, such buildings don’t come cheap – they could cost upto 20% more than conventional buildings. But, the amount of energy they save allows them to pay back for such additional cost in around 17 years. And do bear in mind that this does not include any revenues and benefits accruing from carbon credits that are earned through prevention of greenhouse gases (GHG).

Moreover, such costs could be mitigated in other ways.

Take, for instance, the KEF group which has just launched the KEF Industrial Park, in Tamil Nadu, the only integrated facility for off-site (pre-fabricated) manufacturing for the construction sector in India. Its promoter, Faizal Kottikollon, promises to reduce construction costs by 7% because of economies of scale, and another 30% on account of interest-cost-savings on account of the compressed time frame within which buildings can be built.

Together, Bayer’s technologies and KEF’s solutions could actually reduce the cost of constructing environmentally friendly buildings.

In fact, creating an environmentally friendly city, replete with world class waste management systems in place, should not cost much. Erik Freudenthal, (www.hammarbysjostad.se) Head of Communications, Glashus Ett – The Environmental Information Centre for Hammarby Sjostad, Sweden, believes that if a city is planned well, and holistically, the incremental costs should not be more than 2-4%. He should know because he has worked with the best of such cities in Sweden and elsewhere.

What is a smart city?

Smart cities incorporate some key concepts that almost any modern city is bound to have – in Korea, China or Singapore. They usually house populations of 1 million or more. While planning the city, care is taken to ensure that all drainage systems, water, electricity and gas utilities, and waste management systems are put in place right at the outset. The master plan clearly identifies industrial, residential, commercial educational, entertainment, recreation and shopping areas.

All these are designed in such a way that no residence or place of work is more than five minutes away from a mass transport system (bus, metro or train). Thus, the need for private transport gets minimised, in turn allowing for a better environment. Typically, since cities also promise security and stability, expect lots of surveillance equipment to be in place right from the beginning. Also expect Information and Communications Technology (ICT) to play a big role in administration. Unlike sprawling cities of the previous centuries, modern cities have compact buildings, thus offering better management of drainage and utilities.

And since, no city can be appealing without good schools and hospitals, care is taken to ensure that such social infrastructure is in place before the factories and workplaces come up. Once the workplaces are ready, workers move in with their families, and the usual hum of a well-ordered city begins to remind everyone that this is a vibrant, liveable city.

Constitutional shelter needed

Yet, it must be remembered that smart cities are not only about constructing eco-friendly buildings. They are highly conceptual in nature, working on ways to make a city which actually changes the quality of life and even the day-to-day cost of living there. Good cities also require good administration. That is why India decided to build the best of its cities under the shelter of Article 243-Q of the Indian Constitution which provides for independent (non-political) administration of cities identified as “industrial” cities.

It is this constitutional shelter that allowed Jamshedpur to remain relatively free from political machinations that had engulfed and devastated Bihar for three decades since the 1970s. It is under this protection that NOIDA was set up near Delhi (NOIDA has a CEO, not a political head). Conventional cities, invariably, in India at least, encourage the formation of slums for the creation of vote banks on the one hand, and real estate gains on the other . Political interference corrupts the police and other administrative authorities, and makes them turn a blind eye to usurpation of pavements by hawkers and slum-dwellers, and of road space through illegal parking. Industrial cities set up under this constitutional shelter are more likely to be capable in effectively dealing with such problems.

When the 24 DMIC cities were proposed – six in the first phase – the plan was to set them up as “industrial” cities. This required each state (where a DMIC city was to come up), the investing partner (Japan in this case) and the DMIC Development Corporation to enter into a tripartite agreement allowing for the autonomous functioning of such cities. The cities could collect their own property taxes, money for development rights etc and use the funds to finance the development, growth and administration of such urban centres for a period of around 30-50 years.

It is not clear if the new cities currently being planned will be built under this constitutional shelter. If yes, good. If no, then we will have to first work towards educating the political class in framing inviolable rules relating to parking, hawkers, slums, and quality of construction of roads and buildings. And all of them must be environmentally sustainable.

COMMENTS