Moneycontrol carried a modified version of this article at https://www.moneycontrol.com/news/business/coronavirus-pandemic-an-opportunity-to-overhaul-indias-ailing-healthcare-sector-5079501.html

Coronavirus II –

Needed an overhaul of medicare: more free testing, more accountability

RN Bhaskar

The first part of this series appeared at http://www.asiaconverge.com/2020/03/coronavirus-pandemic-risk-contagion-india/

On the night of 24 March, the prime minister informed the entire country that India was under a total lockdown for 21 days. Nobody denies the need. But the informed are convinced that the danger signals will continue for several more months.

There was a time when India could have said no to the pathetic sums being spent by the government on health services. When India could have ensured that the government took human development index a lot more seriously than it has for the past seven decades. But we didn’t. As a result, many of the decisions the government takes today are a direct result of a crumbling health infrastructure. It is a system that does not record data for analysis (Rajeev Sadanandan former health secretary in Kerala who was in charge of controlling the Nipah virus outbreak has bemoaned this publicly quite often). And it works under a bureaucracy that is more comfortable with bans than with finding workable solutions.

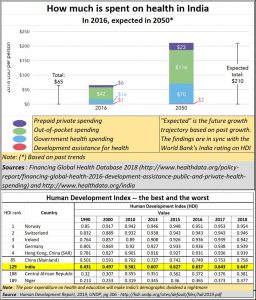

Today, according to the figures released by the government in Oct 2019, India spent barely 1.28% of its GDP on health services in 2017-18. Moreover, in an age of computerization, and the national data network, it is worrying that up-to-date statistics are still not being made available – for health, education or agriculture – all of them key sectors of the Indian economy.

Today, according to the figures released by the government in Oct 2019, India spent barely 1.28% of its GDP on health services in 2017-18. Moreover, in an age of computerization, and the national data network, it is worrying that up-to-date statistics are still not being made available – for health, education or agriculture – all of them key sectors of the Indian economy.

According to the National Health Profile (NHP), 2019 (http://www.cbhidghs.nic.in/WriteReadData/l892s/8603321691572511495.pdf), general government health expenditure in 2015 was just 3.4% of general government expenditure. This was against 8.5% spent by governments in the region. It is not surprising therefore that India’s HDI rankings are terribly poor – above countries like Niger, but below almost every developed and developing country (see chart).

In the same NHP report, Acute Respiratory Infection in India accounted for 3,254 deaths (of 4,21,99,633 registered cases) in 2017 and 3,740 deaths (4,19,96,260 cases) in 2018. Deaths on account of pneumonia were 4,105 (7,59,004 cases) in 2017, and 4,213 (9,28,485) in 2018. Both these diseases are relevant here because the Covid-19 mimics respiratory and pneumonia deaths. India has thus not been a stranger to thousands dying on account of poor healthcare.

Sadly, people also pay heavily for much of their healthcare needs – often from the private sector. The government’s contribution to the country’s healthcare needs is pathetic (see chart). This is despite the government running so many hospitals, dispensaries and primary health centres (PHCs). As a doctor quipped, the way they make you wait in PHCs to get simple treatment for simple ailments has made the PHCs neither primary, nor even health centres. Poor people ignore the PHCs because they cannot afford to lose a day’s wage. And when they need a doctor’s attention, the PHC is ill-equipped to provide secondary or tertiary care. This is happening with Coronavirus tests too.

Earlier the ICMR insisted that if private clinics are allowed, they should offer testing facilities free of costs to the people who want it and get reimbursed by the government. The government has done an about-turn. Despite discussions lasting over a fortnight, it was finally decided that private clinics could charge patients Rs.4,500 per test. This was disclosed yesterday by one of the 12 ‘approved’ private pathology companies in an investor tele-conference. It said that it would initially do some 100 tests a day, mostly in Mumbai and then go up to 1,000 a day. This means that common folk that cannot afford Rs.4,500 for a Covid-19 test will either go without it, or be compelled to go to the shabbily managed government centres. So much for controlling the spread of virus infection. Isolation wards in government hospitals still have common toilets – a major source of infection — and unsanitary conditions.

Had India’s health services been good, India could have opted for measures other than a lockdown. It could have adopted the Singapore model. The televised message of the Singapore prime minister on 12 March is relevant here (https://www.facebook.com/125845680811480/posts/3111854648877220/). Singapore has not shut schools and offices and its people do not wear masks. But there is constant monitoring and testing, and the confirmed are immediately isolated and treated.

Or it could have done what Japan does (https://asiatimes.com/2020/03/japans-winning-its-quiet-fight-against-covid-19/). Unlike Singapore which registered only two deaths from Covid-19 as of 24 March 2020, Japan has registered 49 deaths. Yet Japan adopts a “don’t ask, don’t tell” strategy, based on minimal testing and buttressed by information massage. It treats the ones identified. But like Singapore, it too has ensured national calm and continued economic activity.

Both countries have depended on information technology and a medical system geared to tackle emergencies and offer the finest of healthcare services – whether related to trauma or pneumonia. India could have been urged to adopt such a system, and not cripple commerce, had its medical systems been dependable.

That is why it is now urgent to try create a system which takes away this vital service away from the government. One good option is through the insurance regulator. This way, there will be a government appointed regulator, but the responsibilities allow it to take a holistic view of the entire medicare sector.

Why should the insurance regulator get involved? First, because it deals with medical insurance. Second, because as of now it does not reimburse people for their pathology related expenses. This is unfortunate because – as everyone knows – testing allows people to know what their future ailments can be. That could allow insurance companies to recommend preventive measures to reduce the risk for both the individual and for the insurance sector.

For instance, had the insurance regulator overseen the medicare sector, it could have spoken to all real estate developers and worked out a deal: Mumbai alone has 4,8 lakh unsold flats; India has 1.1 crore vacant flats (https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/economy/mumbai-has-highest-vacant-housing-inventory/article22553704.ece#). . Entire buildings lie vacant. Builders reckon it will take them five years to sell this stock. But they could be given at a nominal rent to hospital chains for five years, to convert them into isolation wards, each room with an attached toilet. The costs would be manageable if the entire insurance sector, with government subsidy for the crisis, backed it. The insurance sector has the money clout, the medical experts and the long-term vision. The government is driven by politics, insurance companies by hopes for long term stability and viability.

Take pathology. As Thyrocare’s managing director, Dr. A. Velumani , stated at a conference in Mumbai (https://www.freepressjournal.in/fpj-initiatives/game-of-volume-works-in-healthcare-thyrocare-cmd-dr-a-velumani-at-fpj-health-conference), pathology is a game of volumes. At the right volumes, costs are just 15% of the revenues. He decided to crash prices of medicare considering the interests of both shareholders and society.

The insurance companies could adopt the Velumani model. Give insured people a 60% rebate on the list prices for pathology tests. The out-of-pocket expenditure of people will decline, people will now have a bigger incentive to take up a medical policy (the tax benefit advantage has been nullified by the latest budget), the insurance company benefits because of more registrants for insurance including the young, and the pathology companies benefit because the insurance companies can drive volumes.

The insurance companies could adopt the Velumani model. Give insured people a 60% rebate on the list prices for pathology tests. The out-of-pocket expenditure of people will decline, people will now have a bigger incentive to take up a medical policy (the tax benefit advantage has been nullified by the latest budget), the insurance company benefits because of more registrants for insurance including the young, and the pathology companies benefit because the insurance companies can drive volumes.

If the insurance regulator were to manage healthcare, he should take the funds allocated for Ayushman Bharat and make it succeed. Currently, the scheme just cannot work. (https://www.moneycontrol.com/news/business/opinion-ayushman-bharat-is-a-great-concept-but-where-are-the-doctors-2851461.html). There are not enough doctors — India has just 1.3 hospital beds and 0.8 physicians for every 1,000 people, and poor systems will instead ensure poor delivery of services and end up making it a great opportunity for corruption.

Were insurance companies to enter the medicare regulatory sector, the corruption in the FDA would ease. Currently every approval – for a vaccine, a cure, or a new medical product, is cleared by the FDA only after it is satisfied. But as the FSSAI episode involving Nestle showed (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2015/06/fssai-bans-and-corruption/), the capriciousness in the FDA is tremendous. People talk about the other C-virus – corruption.

A powerful regulator driving the medicare business will be able to counter the FDA leeching on chemists and druggists and pharma product producers as well.

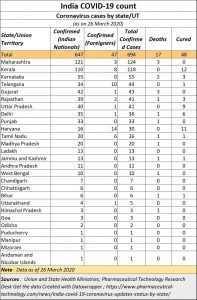

In fact, that will help people get better results of infections in India (see chart).

Currently, on account of very little testing, the Covid-19 data churned out by the government on infections is hardly credible. As Dr. T Sundararaman, former director of the National Health Systems Resource Centre pointed out a week ago “Bihar has only one testing centre . . . . . Having just 52 centres across India makes no sense. And not even all of these are fully functional” (https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/low-testing-could-explain-indias-small-covid-numbers/articleshow/74661955.cms). For instance, even today, the country’s poorest state, Bihar, shows only 3 cases and one death. And with private testing being priced at Rs.4,500, the accuracy of results all over the country will still not be known.

Again, insurance companies could possibly league up with the likes of the U.K.-based Mologic Ltd., in collaboration with Senegalese research foundation Institut Pasteur de Dakar (https://www.bloomberg.com/amp/news/articles/2020-03-16/ten-minute-coronavirus-test-could-be-game-changer-for-africa) which promises to bring down the cost of covid-19 testing kits to just $1 and the time for testing to 10 minutes. That could be a game changer. Insurance companies could renegotiate faster with private clinics than the government can. — could be a gamechanger for the world in less than three months’ time.

For now, there is a lockdown for three weeks. Much of business will be crippled. But during this period, maybe the government could save future generations by overhauling the administration of the medicare sector.

COMMENTS