https://www.freepressjournal.in/analysis/policy-watch-india-is-slipping-on-exports-and-employment

Focus on two E’s needed – exports and employment

RN Bhaskar

Work on the coming year’s annual Budget has commenced. The Finance Minister has invited suggestions from people on what should be done. At the same time, the Economic Affairs secretary will be busy drawing up his vision for a more vibrant India.

At such a time, it is crucial that these columns highlight why focus on to sectors – exports and employment — should be given topmost importance. And in doing so, there is a need to persuade the government to reorient many of its policies that have actually done immense harm to India’s core economic strengths.

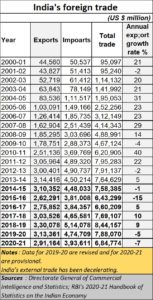

Even a cursory look at India’s export figures will confirm that India’s exports have been flagging. While the pressure on exports has been evident since 2009, it is more markedly so since 2014-15.

Even a cursory look at India’s export figures will confirm that India’s exports have been flagging. While the pressure on exports has been evident since 2009, it is more markedly so since 2014-15.

A further drill down on the numbers shows that the past seven years have actually seen a  sharper deceleration in exports than the earlier seven years. Clearly, there is something happening which has caused India’s export thrust to get blunted.

sharper deceleration in exports than the earlier seven years. Clearly, there is something happening which has caused India’s export thrust to get blunted.

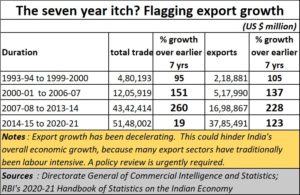

A good way to do this is to look at exports right from 1986-87. That was when India was doing badly. Then break up the entire period till 2020-21 into five seven-year periods. The first seven year period ending 1992-93 was a weak one.

Change came from 1990-91. Thus the second seven-year period ending 1999-2000 registered a growth of 95% in total trade, and 105% in exports over the earlier period.

The next seven-year period ending 2006-07 saw these number rise even further by 151% and 137^ over the earlier period.

This rate accelerated to 260% and 228% in the following period compared to the earlier one. Then came the slump. During 2014-15 to 2020-21, trade growth slowed to just 19% over the previous period, while exports slid to 123%. India was slipping back to the 1980s.

Noted economist Arvind Subramanian calls this India’s Stalled rise: how the state has stifled growth (https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/india/2021-12-14/indias-stalled-rise). This paper is an update of an earlier talk given on 8 October 2021 at Brown University, USA. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XVXm57tD7tQ).

A major problem is that unlike most countries in the world, India’s trade with its immediate neighbours is only 5% of total trade. Most countries do much of their business within their region. Even trade with Asia is just around 40% says Ravi Boothalingam, Founder & Chairman of Manas Advisory (https://asiaconverge.com/2021/12/india-china-the-long-view/). This effectively means that almost 60% of trade is carried out with regions far away. This may have to change, if exports are to be accelerated.

Looking back

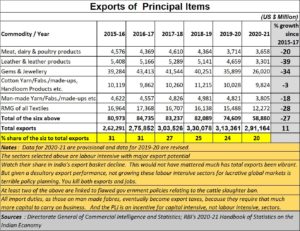

This is when we must take a step back and look at the biggest exports from India –

- meat, dairy, and poultry products

- leather and leather products

- gems and jewellery

- cotton yarn/fabs/made-ups etc

- manmade yarns, fabs madeups

- textiles

These six items used to account for almost 31% of India’s export basket in 2015-16 (see chart). Something caused the share of these six products to decline in India’s export basket progressively, year after year since then. Today, they account for only 20% of India’s exports.

These six items used to account for almost 31% of India’s export basket in 2015-16 (see chart). Something caused the share of these six products to decline in India’s export basket progressively, year after year since then. Today, they account for only 20% of India’s exports.

But why should these six sectors matter? There are several reasons for this,

First, all these sectors are labour intensive. They contribute significantly to wealth generation at the bottom of the pyramid, crucially important for a developing, populated country like India.

Secondly, all the six, except maybe gems and jewellery, account for a high value added or VA (https://asiaconverge.com/2021/12/corporate-groups3-where-did-the-va-go/). This is important because it means more wealth being added to basic raw material, than say petroleum exports, or even engineering exports. A high VA means that money paid to the government as taxes, or to bankers as interest, or shareholders as dividends, or wages to the workforce or even money retained by the company is money that stays in India, and shared with many people.

What this means is that – in one way or the other – government policies have hurt both employment potential and exports from lucrative sectors that are crucially vital to India’s growth. It is no surprise therefore that India’s record on unemployment, at 23% of youth, is one of the worst in the world among developing countries (see Kaushik Basu’s tweet on the World Bank’s figures at https://twitter.com/kaushikcbasu/status/1428204908965240832?s=20).

India needs to create at least 12 million new jobs (in addition to  jobs that are lost either through technological advances, or ineptness). The sad truth is that India has not been able to generate that many more jobs. On the contrary, there is growing evidence that there has been a destruction of jobs (https://asiaconverge.com/2021/05/shrinking-modi-bjp-even-india/) which in turn has reduced the country’s purchasing power, shrunk the demand economy, and pulverised millions of people into poverty (https://asiaconverge.com/2021/06/can-africa-become-the-new-market-to-stump-india/).

jobs that are lost either through technological advances, or ineptness). The sad truth is that India has not been able to generate that many more jobs. On the contrary, there is growing evidence that there has been a destruction of jobs (https://asiaconverge.com/2021/05/shrinking-modi-bjp-even-india/) which in turn has reduced the country’s purchasing power, shrunk the demand economy, and pulverised millions of people into poverty (https://asiaconverge.com/2021/06/can-africa-become-the-new-market-to-stump-india/).

In fact, as a CARE Edge report on Employment (“Jobs were lost in 2021” dated 17 December 2021) shows, 28 sectors registered job losses in 2021 over 2019. Only seven showed increases in employment. The situation is alarming.

Unfortunately, few are willing to talk about the reasons for these body blows the Indian economy has received.

Reasons

One obvious reason is the introduction of cattle slaughter laws. That affected leather and meat markets. They also impoverished farmers who used to get Rs.20,000 on an average for each old cattle. If the lawmakers do believe that there ought to be a ban on cattle slaughter, go ahead. But first pay each farmer Rs.20,000 for each old cattle which he cannot sell. This money, along with borrowed money, allowed him to purchase a young milch cattle and continue his business of earning through milk production. Instead, he was left with fewer cattle, and increased expenses on account of ageing cattle which he was not allowed to sell. Thus, farmer impoverishment, labour shrinkage (both leather and meat industry are labour intensive) and rural poverty were in the ascendant. These policies must change (https://asiaconverge.com/2021/05/agenda-1-dont-meddle-with-the-dairy-sector/).

Another factor was introduction of policies that hurt the garment and textiles sector. As these columns described a few weeks ago, this is one sector that can boost both exports and employment. Can the economic survey and the budget incorporate those suggestions as well (https://asiaconverge.com/2021/11/indias-textiles-and-apparels-can-achieve-a-lot-more/). Efforts must be made to ease the burden of GST compliance that has bedevilled small traders and entrepreneurs in this sector.

A third way would be to actually discourage legislations aimed at destroying jobs. A good example is the way the Gujarat government wanted to ban non-vegetarian stalls near stations. Besides being discriminatory, the move would destroy jobs, especially if the stalls were licensed. If they are unlicensed, the rule should apply to all vendors, not just one section of them.

There are already laws and Supreme Court judgements against any attempt to stop meat wagons and harass the drivers of such wagons (sometimes they have been beaten to death). A minimum punishment of 10 years’ imprisonment should be awarded to such people, because they have taken law into their own hands, and because they destroy jobs and business.

If India wants to grow, it must make doing business easy, not hazardous. Then focus on two other areas – education and health, and agriculture. But they are subjects that will be dealt with later.

COMMENTS