Policy watch

India excelled in the art of earning its wealth, not plundering it

By RN Bhaskar

This is a story not just for historians, but for India’s policymakers. It tells of how Indian entrepreneurship can be truly unlocked if they are allowed to work in harmony. That means a country where you don’t have screaming mobs railing against one community or the other. It also talks about how a heavy-fisted regulatory approach only shrivels business talent and enterprise. Most of all, it is about how India became the world’s sink for gold.

How India emptied Rome’s coffers

How India emptied Rome’s coffers

This is a story about how India was adept at earning gold, and making the country rich. It is about the trading, exploratory and commercial skills that Indians, especially those from South India, had and still have. The original inspiration for this article came from a book by Kanakalatha Mukund and the introduction to this book by Gurcharan Das.

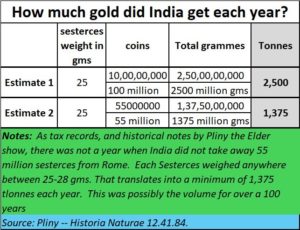

In fact, going by the records of Pliny the Elder in 75 AD, there was “no year in which India does not drain our Empire of at least fifty five million sesterces” (Pliny — Historia Naturae 12.41.84, also in the statement by historian William Dalrymple — https://twitter.com/DalrympleWill/status/1421487444587913216).

In fact, going by the records of Pliny the Elder in 75 AD, there was “no year in which India does not drain our Empire of at least fifty five million sesterces” (Pliny — Historia Naturae 12.41.84, also in the statement by historian William Dalrymple — https://twitter.com/DalrympleWill/status/1421487444587913216).

Elsewhere, records in Rome show an outgo of 100 million sesterces (https://edurev.in/question/2324566/Which-Roman-wrote-In-no-year-does-India-draw-our-empire-of-less-than-five-hundred-and-fifty-millions). Verification of such numbers come from an examination of tax records of that period. This could mean that China earned the rest. It too was trading with Rome and sold its silk through the Arabs. And as computations by Angus Maddison show (https://asiaconverge.com/2023/09/china-and-india-matter-a-lot-more-than-the-world-thinks/), India’s trading and business volumes 2000 years ago were significantly larger than those of the Chinese.

The South Indian merchants’ prowess was on account of several factors.

First, they were excellent seafarers, better than those from other Southeastern countries.

Second, the harmony that these people showed in working together irrespective of religious affiliations. The Tamil side of this subcontinent had excellent pearl divers as well, and produced some of the finest pearls. Even today, some of the best pearl divers come from this region.

Third, it was an amorphous society, where almost all the sea farers were animists, not Hindus. They were shunned by Hindus because they indulged in traversing the oceans. That was forbidden. It was considered inauspicious, making the people who indulged in this activity impure. Rowing boats across rivers was acceptable; but rowing them across the seas and oceans was not.

The best (mythological) proof of this was the way one of the Hindu gods, Lord Rama, happily took the boat while crossing the Ganges. But when he reached Kanyakumari, the southernmost tip of this peninsula, he was confronted by the ocean. His wife, Sita, had to be rescued from the clutches of the Sri Lankan king, Ravana. He prayed to the sea goddess (Many texts refer to the Sea God Varuna) to let him have a safe passage across the Palk Straits to reach Sri Lanka. But the Goddess forbade him. She asked him to build a bridge instead, which is today known as Ram Setu.

Even as recently as in the 19th century, when some of India’s legendary freedom fighters like Mahatma Gandhi returned to India after studying overseas, they were compelled to undergo a purification ritual, because they had become unclean and impious by crossing the oceans. That purification ritual was known as shuddhikaran.

Unbound and unaffected by the rules of Hinduism, the seafarers created their own community and learnt to live in harmony. They became excellent traders, and tenacious fighters as well. Some of them opted to travel to China, where they offered sandalwood and pearls, and took back silk. India, as Mukund points out in her book, was the place where the oysters had pearls as large as teeth (Sirupanarruppadai, 62, quoted by Kanakalatha Mukund in her book The World of the Tamil Merchant).

Some believe that the growth of the silk industry in South India has its roots in this period when silkworms too were brought back. Some others undertook shorter routes from the Tamil side, through the Palk Straits, to smaller ports on the Eastern side. Major ports like Muziris (now a sunken city) on the Kerala side came up only a little before the 3rd century AD.

Then when Buddha was active during the 6th century BCE, some of them opted to become Buddhists (there were animists earlier, worshipping nature). Moreover, Buddha himself traversed the oceans to go to Sri Lanka on at least two occasions.

Later, when Islam was born in 600 AD, many of the seafarers opted for Islam. But the old bondages of a common past kept the seafaring community a united one. This was true even after the 8th century, when Adi Sankara worked towards the revival of Hinduism, and coopted seafarers and tribals into Hinduism.

As Mukund explains in her book, “Large ships from the west came to these ports because of the vast quantities of pepper and malabathrum, the leaf of the cinnamon tree used as an aromatic, available there. Goods brought in by these ships included large quantities of coins, topaz, antimony, coral, crude glass, copper, tin and lead, some wine and a small quantity of textiles. The ships took back pepper, vast amount of pearls, ivory, silk cloth, spikenard, a fragrant ointment or oil from the Gangetic region, malabathrum from the interior, transparent stones, evidently beryls, diamonds, sapphire and tortoiseshell. Tortoiseshell was brought to Musiri [also known as Muziris] from islands near Malaya . . . This list of the exports from Rome and imports into Rome from Tamilakam clearly exemplifies the adverse trade balance of Rome due to the high value of the luxury goods imported from India, which had to be made up by the export of silver and gold coins.”

Initially, Indian boats from the Tamil side would take their small quantities right up to Rome, often using Arabs as intermediaries. Then, Rome began sending its ships to India to eliminate the hefty margins Arabs charged. But as there were no large ports on the Kerala side, they anchored as close to the shore, and its people went by foot from the Kerala side to the Tamil Nadu side of the peninsula. On the way, they would pick up huge quantities of spices, especially pepper, sandalwood and silk among many other items. They would then engage boats on the Tamil side, which would travel through the Palk Straits (the big Roman ships could not negotiate these shallow and treacherous rocky waters) and load the goods on to the Roman ships. Gradually, Muziris became a major port, and the Romans even built a garrison there to keep the Arabs away. Goods would now be assembled at this port city for being loaded on to Roman ships. Today, Muziris is a sunken city (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ylrrHB5oF24).

The Romans loved Indian spices and silks. Their appetite for pepper was inexhaustible. That in turn made the Senate quite apprehensive as Indians were taking away huge quantities of gold in the form of the Roman sesterces as payment for their goods. On at least three occasions between 100 BC and 300 AD, Rome warned its senators to advise their wives to go easy on spices and silk consumption. But their appetite only got whetted. On one occasion it even tried to ban trade with India. But the ban did not work. By 300 AD, Rome had exhausted all the gold in its treasury. It was compelled to issue coins in base metals instead.

It was possibly the downfall of the Roman empire which reduced purchasing power, or maybe it was the reluctance of the South Indian seafarers was the reluctance to accept base metal coins. But exports to Rome slowed down. By 300 AD, exports to Rome began shrinking. India’s accumulation of gold also slowed down.

But trade shifted to the Persian Gulf. India’s trading instincts could not be quelled.

Gold storage

Much of the gold earned was retained in South India itself. After the revival of Hinduism, temples became the place for all commerce and transactions, for all religions and cultures. As the ruins of Hampi, will testify, the space between the temple and the palace became a marketplace.

The temples soon became banks which stored the gold as well. Incidentally, even the Romans kept their gold in temples. It was stored in the Temple of Juno on Capitoline hill. There were 3 temples there. The other temples were Jupiter Optimus Maximus and the temple dedicated to Minerva. Juno’s temple was also the mint & treasury. Temples were sacrosanct. Both in Rome and in India.

Incidentally, contrary to popular perception nowadays, Muslim rulers also became guardians of temples. A remarkable incident is the way Sringeri, one of the key centres set up by Adi Sankara, was plundered by a splinter group of the Marathas. It was Tipu Sultan who sent his army there and guaranteed this place royal protection. Even today, Muslims walk through this Hindu sacred centre without fear — a testimony to the amity that Tipu Sultan guaranteed. Even today, temples are on the warpath with the government of India which wants to control temple earnings and their gold.

Fortunately, the Cheras, Cholas and the Pandyas were strong enough, and far from the Khyber Pass, and hence could remain insulated against much invasion. When Kanishka heard of this, he picked up much of this gold — one does not know through plunder or trade — and melted the gold to mint his own coins. Interestingly, South India’s gold brought in others as well.

The British too wanted to control the mining of the Kolar and Hutti gold mines in Karnataka. That was key driver for the rapid development of Bangalore. That is why Bangalore got electricity before most of Europe (7th or 8th city in the world to have electricity). But this largesse was to take away gold from India.

Unlike many other nations, India (and China) earned the gold. They earned it through trading. When the Romans offered to trade their goods with Indians in exchange for the silk and the spices, Indian sea farers weren’t interested. Nor was China, when the British wanted their tea in exchange for their fabric and other goods. Britain then thought of the opium trade, because it did not want to part with its gold, which in case was largely through plunder.

Even the US earned its money through plunder – it adopted reverse colonisation by bringing Africans to its land as slaves. It used their sweat for its wealth. In the second World War too, the US made money through the sale of weapons. This activity is probably one of the largest revenue generators for the US even today.

India began losing its gold after the British colonised India. Unfortunately, when it got independence, the government of India drove gold underground by imposing all types of restriction on this yellow metal. When it was lifted, except for a brief period of enlightened policymaking, high import duties were slapped on gold, pushing it underground again.

India continues to love its gold. Almost 80-100 tonnes of gold get smuggled into the country each year (https://asiaconverge.com/2020/10/gold-smuggling-i-is-encouraged-by-flawed-government-policies/). Barely 3-5 tonnes get confiscated by the authorities. According to the trade, the moment import tariffs cross the 5%-mark, gold smuggling becomes very attractive. Today, with a 15% import duty, plus other taxes, the final loading is over 18%. Smuggling has been made extremely attractive. The government’s hunger for more and more money (to finance its vote banks) through import duties, has driven gold underground once again.

Can India regain its earlier heights of glory when it had become the richest nation in the world? Yes, maybe. But only if the right policymakers take charge of the economy. Consider how, even the nation’s central bank, the RBI, opted to keep more than half its gold overseas (Free subscription — https://bhaskarr.substack.com/p/rbi-seeks-to-conceal-govt-deficit?sd=pf). When public outcry became shrill, it brought back 100 tonnes of over 400 tonnes lying overseas.

The author is a senior journalist and researcher

======================

Do view my podcast on this subject at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ibJJXeGyZxA&t=33s

COMMENTS