http://www.moneycontrol.com/news/business/dear-pm-modi-heres-how-bureaucrats-are-planning-to-scuttle-your-rooftop-solar-employment-plans-2468501.html

Sabotaging rooftop solar and employment generation

At best, the government’s solar plan Sristi can be described as the work of incompetent officials. At worst, it is the handiwork of crafty bureaucrats who wanted to see the government’s push for solar rooftop to fail.

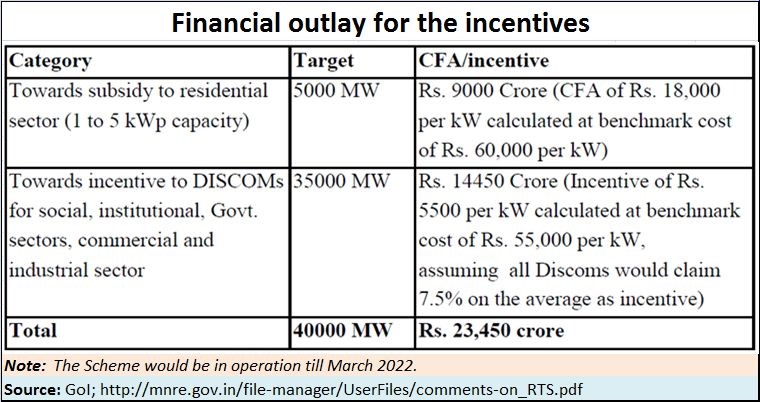

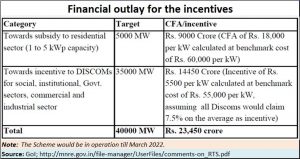

From the look of it, the bureaucracy seems bent on sabotaging Prime Minister Modi’s plan to create jobs, encourage solar and ensure power for all. The ministry has set aside Rs 23,450 crore for rooftop solar. But look closer, and it strikes you as a joke. More so, if one considers the sequence of events.

The sequence

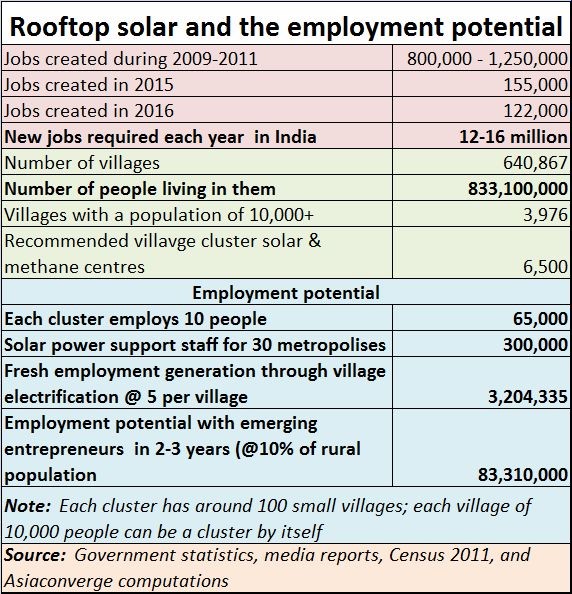

On October 11, 2017, Moneycontrol wrote about an electrification plan that could create 83 million jobs (http://www.moneycontrol.com/news/business/economy/the-electrifying-plan-that-would-create-83-million-jobs-from-solar-energy-2410301.html). from solar energy.

The article talked about the need to focus on rooftop solar. It made a case for decentralised clusters in the hands of private entrepreneurs, which would actually fulfill the government’s agenda of power for all.

It talked of the enormous employment potential rooftop solar held out for India if it adopted the German model advocated by the late minister Hermann Scheer. And it talked about ending the current subsidy regime with a new one, which could let the entrepreneur encourage wealth generation in rural areas (the table below is a snapshot of all that was written about in that article).

On December 18, the ministry came out with a paper on rooftop solar (http://mnre.gov.in/file-manager/UserFiles/comments-on_RTS.pdf). Termed as a concept note, it talked about SRISTI – an acronym for Sustainable Rooftop Implementation for Solar Transfiguration of India.

On December 18, the ministry came out with a paper on rooftop solar (http://mnre.gov.in/file-manager/UserFiles/comments-on_RTS.pdf). Termed as a concept note, it talked about SRISTI – an acronym for Sustainable Rooftop Implementation for Solar Transfiguration of India.

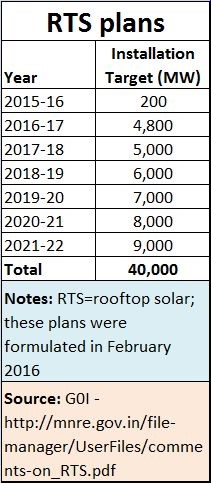

The plan was an attempt to take the dust off of an older policy announced in February 2016.

The government had finally, after several years of exhortation by this author, agreed to focus on rooftop solar.

Sristi, the way it has been designed, is laughable because of several reasons.

First, it is just a rehash of a decision that was taken in February 2016, to permit 40 GW of rooftop solar (http://www.asiaconverge.com/2016/06/solar-power-the-agony-and-the-ecstacy/).

There was nothing new about this concept note that sought to transfigure India.

There was nothing new about this concept note that sought to transfigure India.

Second, the only thing new about this plan is the allocation of subsidies to various states. The total value of incentives works out to an impressive Rs.23,450 crore. But the manner in which this incentive has been apportioned is unimaginative and bizarre. It will create huge problems for power distribution companies (discoms). They could actually start bleeding more heavily than at the moment.

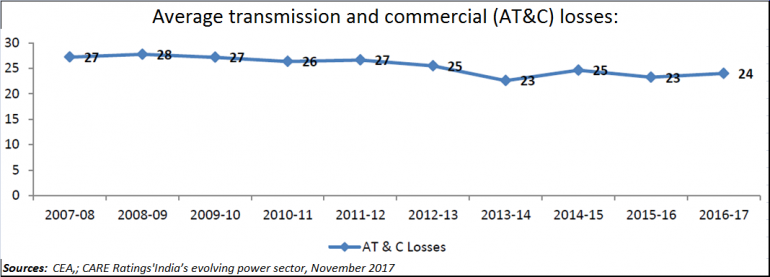

Even after disguising many losses as agricultural consumption, the average ATC losses exceed 24 percent (see chart below). Despite the much-vaunted schemes like UDAY (Ujwal discom assurance yojana), discoms have not been able to return to the 23 percent achieved three years ago. The present Sristi scheme could aggravate the losses. But more on that later.

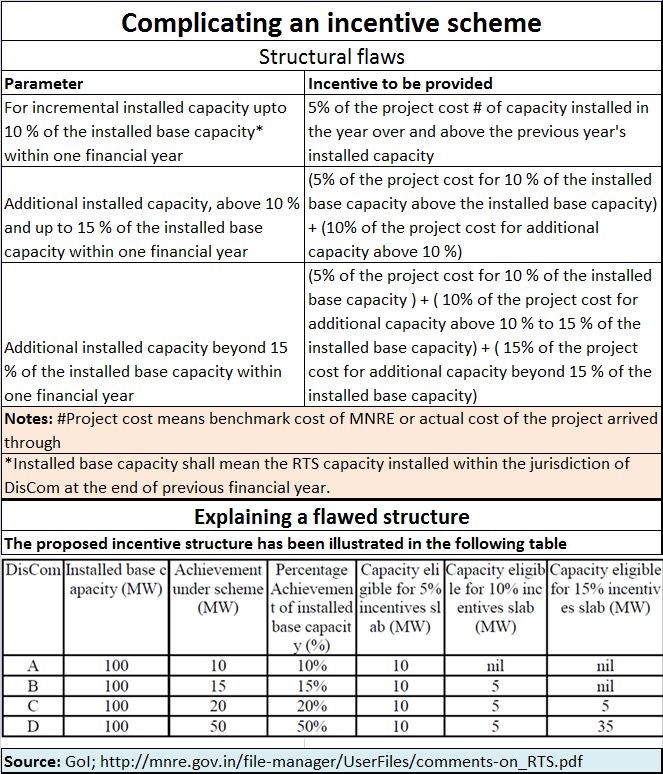

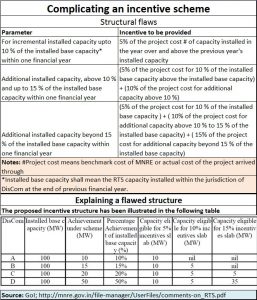

Third, the entire incentive structure is so convoluted (chart below) that it is bound to create more disputes than resolve issues. The only sustainable part about this concept note will be the constant scope for disputes. That will only make the bureaucrat that much more indispensable to adjudicate matters. Since there are no clear-cut guidelines, you can be sure that all these disputes will eventually clog up the courts even more, or make state-owned discoms go bust. It could make the ease of doing business in India a big joke!

Third, the entire incentive structure is so convoluted (chart below) that it is bound to create more disputes than resolve issues. The only sustainable part about this concept note will be the constant scope for disputes. That will only make the bureaucrat that much more indispensable to adjudicate matters. Since there are no clear-cut guidelines, you can be sure that all these disputes will eventually clog up the courts even more, or make state-owned discoms go bust. It could make the ease of doing business in India a big joke!

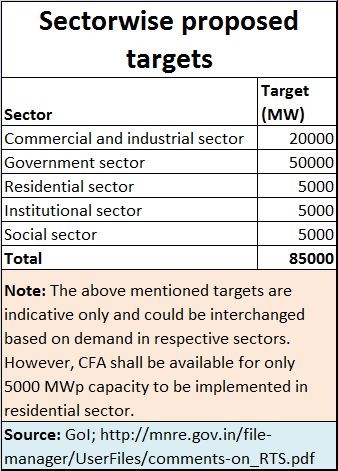

Fourth, the largest potential for solar power lies in rural areas. There is not a word about that sector (see chart). Much of the losses (and theft) come from this category of consumers. Decentralising this sector, and allowing someone to handhold farmers into starting small businesses should have been the way forward. Instead, as the chart alongside shows, there are suggested targets for commercial and industrial sectors, government buildings, residential sectors and others. But there is no mention about the agricultural sector where the opportunities and the challenges lie. Moreover, state-owned discoms are unlikely to be capable of dealing with the existing mess. But it could be through the implementation of a distributed, off-grid cluster power generation model, as advocated by the Moneycontrol article in October 2017.

Fourth, the largest potential for solar power lies in rural areas. There is not a word about that sector (see chart). Much of the losses (and theft) come from this category of consumers. Decentralising this sector, and allowing someone to handhold farmers into starting small businesses should have been the way forward. Instead, as the chart alongside shows, there are suggested targets for commercial and industrial sectors, government buildings, residential sectors and others. But there is no mention about the agricultural sector where the opportunities and the challenges lie. Moreover, state-owned discoms are unlikely to be capable of dealing with the existing mess. But it could be through the implementation of a distributed, off-grid cluster power generation model, as advocated by the Moneycontrol article in October 2017.

In fact, if one allows rooftop solar to be implemented in households and commercial establishments first, without adopting a cluster, distributed, off-grid model, discom losses will mount. This is because the rural sector gets power at around Rs 1.20 a unit. Households get it at around Rs 6. Industry gets it at around Rs 8, commercial establishments at around Rs 12, and malls and hoardings at around Rs 14 (the actual tariffs may vary from state to state, but this is the general pattern adopted all over India). The average cost of power for state discoms is usually between Rs.4-7 a unit (except for states like Himachal Pradesh, which gets cheap hydro power).

In fact, if one allows rooftop solar to be implemented in households and commercial establishments first, without adopting a cluster, distributed, off-grid model, discom losses will mount. This is because the rural sector gets power at around Rs 1.20 a unit. Households get it at around Rs 6. Industry gets it at around Rs 8, commercial establishments at around Rs 12, and malls and hoardings at around Rs 14 (the actual tariffs may vary from state to state, but this is the general pattern adopted all over India). The average cost of power for state discoms is usually between Rs.4-7 a unit (except for states like Himachal Pradesh, which gets cheap hydro power).

The subsidy that the farmer gets when power is supplied to him at Rs 1.2 a unit is cross-subsidised by the higher tariffs paid by householders, industrial and commercial establishments. If you allow non-farm players to get solar power at around Rs.3-5 a unit, state discoms will have less subsidy money to play around with. This could either mean higher taxes on the one hand, or bigger losses on the other. Dispensing with subsidies altogether will not be politically feasible.

The subsidy that the farmer gets when power is supplied to him at Rs 1.2 a unit is cross-subsidised by the higher tariffs paid by householders, industrial and commercial establishments. If you allow non-farm players to get solar power at around Rs.3-5 a unit, state discoms will have less subsidy money to play around with. This could either mean higher taxes on the one hand, or bigger losses on the other. Dispensing with subsidies altogether will not be politically feasible.

Obviously, some bureaucrat has created a concept note that could spell ruin and disaster for the entire country. The only way out, then, will be to discontinue solar power altogether and let status quo prevail.

Is this the kind of sabotage that some bureaucrats are planning? After all, remember how even the Economic Survey 2017 was misled into stating that solar power is more expensive (http://www.moneycontrol.com/news/business/economy/why-the-economic-survey-is-wrong-about-renewables-2390283.html) than other kinds of power. Do some bureaucrats want to give solar a bad name so that power theft and losses continue? Or is it plain incompetence? Someone will have to take a call on this.

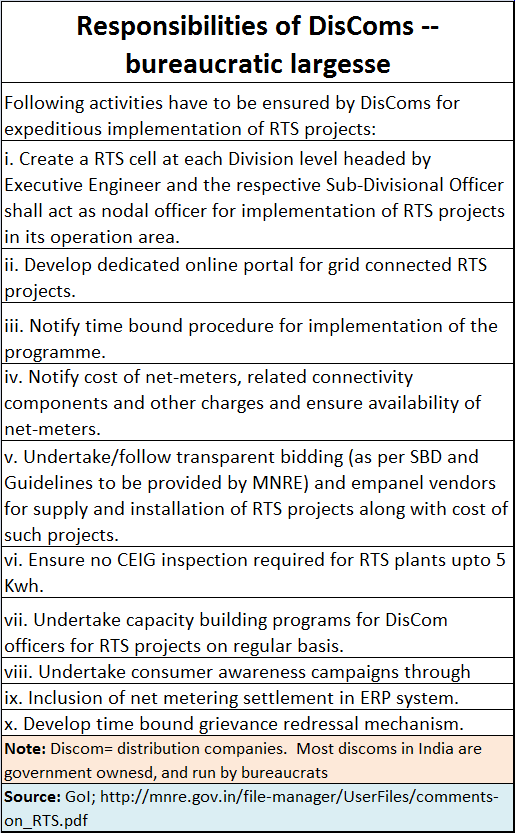

It would appear that the architects of Sristi want to promote state-owned discoms. That is evident from the prescription of dos and don’ts for such companies (see chart). The entire concept note goes against the prime minister’s concept of minimum government, maximum governance. The concept note will make the power sector ungovernable, and help further bloat the size of the bureaucracy.

If the prime minister wants to create jobs, he must focus on rooftop solar. But to make it relevant to India it must be through the decentralised cluster model, financed by capitalising all state losses for ten years. It must cover the rural sector. And he must focus on a middle layer which helped Germany create more jobs than even the automobile sector.

If the prime minister wants to create jobs, he must focus on rooftop solar. But to make it relevant to India it must be through the decentralised cluster model, financed by capitalising all state losses for ten years. It must cover the rural sector. And he must focus on a middle layer which helped Germany create more jobs than even the automobile sector.

Including the rural sector is crucial, because this is where most of the losses and theft take place. The government cannot do this. It needs the involvement of the private sector.

A good example of this is the way Torrent managed to reduce theft and losses in the Bhiwandi district of Maharashtra. This was after several failed attempts by state discom officials to stanch power losses and theft for decades. Torrent did in less than three years what the state could not do in three decades. This has become case study material for most management schools in India.

Sristi can thus be described as the work of incompetent officials at best. At worst it is the handiwork of crafty bureaucrats who wanted to see the government’s push for solar rooftop to fail.

Either way, it is not a happy commentary either on the government or its bureaucrats.

COMMENTS