https://www.moneycontrol.com/news/business/economy/comment-are-strong-governments-bad-for-the-indian-economy-2528037.html

In India, strong governments often result in weak economies

RN Bhaskar – Mar 14, 2018 07:09 PM IST

Could India’s GDP growth rates continue to be subdued in the coming years? The government denies this. It sounds bullish. Its spokesmen state that the economy has bottomed out, and the only way to go is up.

But not everyone is so sanguine. In fact, as pointed out in these columns just a couple of weeks ago (http://www.moneycontrol.com/news/business/comment-from-jobless-growth-to-wary-foreign-investors-the-dark-clouds-on-the-indian-economy-are-here-to-stay-2515845.html) , most economic indicators do suggest some pain ahead. Some economists say that these numbers could be a passing phase.

There are others who, like this author, believe that the GDP numbers may climb by a couple of percentage points. But that could be more because of e-payments, because now merchant discounts also get added to GDP. E-payments alone have the potential of pushing up India’s GDP by a couple of percentage points each year for the next 3-5 years.

Political strength and weakened economy

But there could be a third reason as well.

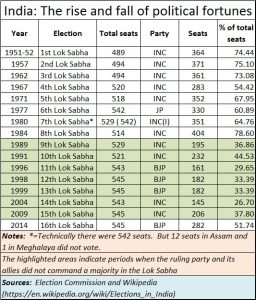

For almost a couple of decades, some political analysts have held the view that India has an inverse relationship between political strength and GDP growth. When a political party enjoys more than 50% of the seats in the government, it has the muscle to bring forth economic changes. But, given the nature of India’s politics, and the need to pander to the support base of the ruling party, decisions get taken that actually adversely affect economic growth.

For almost a couple of decades, some political analysts have held the view that India has an inverse relationship between political strength and GDP growth. When a political party enjoys more than 50% of the seats in the government, it has the muscle to bring forth economic changes. But, given the nature of India’s politics, and the need to pander to the support base of the ruling party, decisions get taken that actually adversely affect economic growth.

This is not true with many other countries. Singapore has a party in power with a majority of seats. But its economic growth has been a global marvel. That could also be because Singapore believes in meritocracy and super efficiency – qualities that are missing in India. Ditto with China. In Russia, a strongman like Putin inherited an economy that was on its knees and gasping for survival. He helped the economy revive.

More power, more appeasement

In sharp contrast, for decades in India, political equations have pushed politicians to promote reservations even without merit being considered. Populism has diluted even educational standards. And greed has allowed politicians to promote limited numbers of medical colleges, even when the country needs more doctors. Donations and capitation fees suddenly become more important than promoting a national health and education agenda.

In sharp contrast, for decades in India, political equations have pushed politicians to promote reservations even without merit being considered. Populism has diluted even educational standards. And greed has allowed politicians to promote limited numbers of medical colleges, even when the country needs more doctors. Donations and capitation fees suddenly become more important than promoting a national health and education agenda.

There is always hope that a strong leader will be able to get such trends reversed. But given India’s political compulsions, and the apparent unwillingness to let the judiciary and law enforcement machinery become stronger, politically expedient measures invariably find favour. That includes selective pursuit of investigation, graft, tokenism and populism.

Consider how violence on the streets has seldom resulted in convictions, even when there is photographic evidence which could easily pin down the miscreants. Consider again how an elected representative was allowed to go scot-free even after slapping a public servant (12 times) and breaking his spectacles. Further, consider how the government allows foodgrain to rot, but will not give it free of cost to the poor (https://www.moneycontrol.com/news/economy/policy/comment-farms-destroy-value-not-because-of-farmers-but-because-of-the-government-2521885.html). And consider how the policy makers now show eager willingness to abandon an existing system of verification, and instead advocate a system of authentication (http://www.moneycontrol.com/news/india/comment-aadhaar-does-not-identify-it-merely-authenticates-thats-an-important-difference-2502509.html). They seem oblivious to the danger of creating an army ghost identities, which can be a security and economic nightmare.

To hell with laws

In fact, what hurts India most is the way politicians have sought – through successive governments – to weaken the judicial and law enforcement arms of government itself. Nothing confirms this as eloquently as the numbers put forth by P Chidambaram (see chart), who was at various times finance and home minister at the centre. It must be clarified though that even under Chidambaram’s watch, judicial vacancies were not filled up, nor were the posts of policemen. He too was not willing to let law enforcement become autonomous, as recommended by commission after commission.

Thus, through every scam, the people who get caught are often junior officers and middle level managers. The top brass – often ministers – who instructed the easing of rules for scamsters often go scot-free. And their crimes of trying to subvert law enforcement are seldom investigated. Thus you have a minister who was believed to have encouraged the Telgi Scam (involving printing of fake stamp papers). His name also cropped up again for trying to auction off police posts, in an article penned by a former police commissioner. Yet these are the crimes that are not being investigated.

Thus, through every scam, the people who get caught are often junior officers and middle level managers. The top brass – often ministers – who instructed the easing of rules for scamsters often go scot-free. And their crimes of trying to subvert law enforcement are seldom investigated. Thus you have a minister who was believed to have encouraged the Telgi Scam (involving printing of fake stamp papers). His name also cropped up again for trying to auction off police posts, in an article penned by a former police commissioner. Yet these are the crimes that are not being investigated.

By not filling up such posts, there is always a backlog of cases. Judicial delays invariably benefit the oppressor and not the oppressed The government (read politicians) then decides which cases to take up for investigation, and which files should be allowed to be left on the shelves to gather dust. That is one reason the government does not like arbitration awards by centres in other countries, because the powerful in India then lose the ability to delay the implementation of the award (http://www.moneycontrol.com/news/india/comment-asking-for-investments-is-good-but-can-india-guarantee-speedy-and-fair-grievance-redressal-2489553.html).

All judicial delays eventually have a price that must be paid for in economic terms. And that, in turn, gets re-elected in poor GDP growth rates.

Power consolidation

And the irony is that when a government becomes strong, it seeks to consolidate its power. That would not have mattered in a meritocracy. But it can be devastating in a system which encourages reservations over merit, privileges over equality before the law.

Hence while a strong leader could be expected to deliver high economic growth rates, the opposite often takes place. Remember, it was at the height of power that Indira Gandhi nationalised banks, abolished privy purses and introduced a crippling industrial licensing system.

Ditto during Rajiv Gandhi’s time.

On the other hand, even though the Narasimha Rao government was the weakest in terms of political numbers, it delivered a modern India. He broke up telecom rules, and delicensed industry among several other measures that he undertook.

On the basis of the numbers, it is possible to say that strong governments do cripple India. They could have helped India, if the strong government were to fill up judicial and law enforcement posts. It would have galvanised India’s march to greater heights if the law enforcement machinery were to be made autonomous.

But as things stand today, that does look a bit fanciful. Coupled with low investment in education and healthcare, and poor focus on outcomes, India may not do as well as desired. If that is true, it is quite possible that a weaker government – which rules through consensus – would actually help the economy. A weaker government automatically allows the judiciary and the law enforcement machinery to become stronger. But that strength is on account of the the political party becoming relatively weaker. Law enforcement could be a great deal healthier if all its vacancies were filled in quickly, the backlog of cases removed, and the rule of law (including accountability of police officials) were allowed to prevail.

But then, is this wishful thinking?

The author is consulting editor with Moneycontrol

COMMENTS